U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Full Report (.pdf, 1.53 mb)

Sponsored by

U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

In cooperation with

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

National Cooperative Highway Research Program

August 2012

Disclaimer

This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers' names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document.

Technical Report Documentation Page

| 1. Report No. FHWA-PL-12-031 |

2. Government Accession No. | 3. Recipient's Catalog No. | |

| 4. Title and Subtitle Managing Pavements and Monitoring Performance: Best Practices in Australia, Europe, and New Zealand |

5. Report Date August 2012 |

||

| 6. Performing Organization Code | |||

| 7. Author(s) Thomas E. Baker, Timothy K. Colling, Judith B. Corley- Lay, Kevin L. McLaury, Nastaran Saadatmand, Roger L. Safford, Richard M. Tetreault, Julius B. Wlaschin, Kathryn A. Zimmerman |

8. Performing Organization Report No. | ||

| 9. Performing Organization Name and Address American Trade Initiatives 3 Fairfield Court Stafford, VA 22554-1716 |

10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) | ||

| 11. Contract or Grant No. DTFH61-10-C-00027 |

|||

| 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Office of International Programs Federal Highway Administration U.S. Department of Transportation American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials |

13. Type of Report and Period Covered | ||

| 14. Sponsoring Agency Code | |||

| 15. Supplementary Notes FHWA COTR: Hana Maier, Office of International Programs |

|||

16. Abstract |

|||

| 17. Key Words Asset management, pavement maintenance, pavement management, performance measures |

18. Distribution Statement No restrictions. This document is available to the public from the: Office of International Programs, FHWA-HPIP, Room 3325, U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC 20590 international@fhwa.dot.gov, www.international.fhwa.dot.gov |

||

| 19. Security Classify. (of this report) Unclassified | 20. Security Classify. (of this page) Unclassified | 21. No. of Pages 76 | 22. Price Free |

Managing Pavements and Monitoring Performance: Best Practices in Australia, Europe, and

Prepared by the International Scanning Study Team:

Richard M. Tetreault (Cochair)

Vermont Agency of Transportation

Julius B. Wlaschin (Cochair)

FHWA

Kathryn A. Zimmerman (Report Facilitator)

Applied Pavement Technology, Inc.

Thomas E. Baker

Washington State DOT

Timothy K. Colling

Michigan Technology Transportation Institute

Judith B. Corley-Lay

North Carolina DOT

Kevin L. McLaury

FHWA

Nastaran Saadatmand

FHWA

Roger L. Safford

Michigan DOT

For

U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

National Cooperative Highway Research Program

August 2012

International Technology Scanning Program

The International Technology Scanning Program, sponsored by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), and the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP), evaluates innovative foreign technologies and practices that could significantly benefit U.S. highway transportation systems. This approach allows for advanced technology to be adapted and put into practice much more efficiently without spending scarce research funds to re-create advances already developed by other countries.

FHWA and AASHTO, with recommendations from NCHRP, jointly determine priority topics for teams of U.S. experts to study. Teams in the specific areas being investigated are formed and sent to countries where significant advances and innovations have been made in technology, management practices, organizational structure, program delivery, and financing. Scan teams usually include representatives from FHWA, State departments of transportation, local governments, transportation trade and research groups, the private sector, and academia.

After a scan is completed, team members evaluate findings and develop comprehensive reports, including recommendations for further research and pilot projects to verify the value of adapting innovations for U.S. use. Scan reports, as well as the results of pilot programs and research, are circulated throughout the country to State and local transportation officials and the private sector. Since 1990, more than 85 international scans have been organized on topics such as pavements, bridge construction and maintenance, contracting, intermodal transport, organizational management, winter road maintenance, safety, intelligent transportation systems, planning, and policy.

The International Technology Scanning Program has resulted in significant improvements and savings in road program technologies and practices throughout the United States. In some cases, scan studies have facilitated joint research and technology-sharing projects with international counterparts, further conserving resources and advancing the state of the art. Scan studies have also exposed transportation professionals to remarkable advancements and inspired implementation of hundreds of innovations. The result: large savings of research dollars and time, as well as significant improvements in the Nation's transportation system.

Scan reports can be obtained through FHWA free of charge by e-mailing international@dot.gov. Scan reports are also available electronically and can be accessed on the FHWA Office of International Programs Web site at www.international.fhwa.dot.gov.

International Technology Scan Reports

International Technology Scanning Program:

Bringing Global Innovations to U.S. Highways

Safety

Infrastructure Countermeasures to Mitigate Motorcyclist Crashes in Europe (2012)

Assuring Bridge Safety and Serviceability in Europe (2010)

Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety and Mobility in Europe (2010)

Improving Safety and Mobility for Older Road Users in Australia and Japan (2008)

Safety Applications of Intelligent Transportation Systems in Europe and Japan (2006)

Traffic Incident Response Practices in Europe (2006)

Underground Transportation Systems in Europe: Safety, Operations, and Emergency Response (2006)

Roadway Human Factors and Behavioral Safety in Europe (2005)

Traffic Safety Information Systems in Europe and Australia (2004)

Signalized Intersection Safety in Europe (2003)

Managing and Organizing Comprehensive Highway Safety in Europe (2003)

European Road Lighting Technologies (2001)

Commercial Vehicle Safety, Technology, and Practice in Europe (2000)

Methods and Procedures to Reduce Motorist Delays in European Work Zones (2000)

Innovative Traffic Control Technology and Practice in Europe (1999)

Road Safety Audits-Final Report and Case Studies (1997)

Speed Management and Enforcement Technology: Europe and Australia (1996)

Safety Management Practices in Japan, Australia, and New Zealand (1995)

Pedestrian and Bicycle Safety in England, Germany, and the Netherlands (1994)

Planning and Environment

Reducing Congestion and Funding Transportation Using Road Pricing In Europe and Singapore (2010)

Linking Transportation Performance and Accountability (2010)

Streamlining and Integrating Right-of-Way and Utility Processes With Planning, Environmental, and Design Processes in Australia and Canada (2009)

Active Travel Management: The Next Step in Congestion Management (2007)

Managing Travel Demand: Applying European Perspectives to U.S. Practice (2006)

Transportation Asset Management in Australia, Canada, England, and New Zealand (2005)

Transportation Performance Measures in Australia, Canada, Japan, and New Zealand (2004)

European Right-of-Way and Utilities Best Practices (2002)

Geometric Design Practices for European Roads (2002)

Wildlife Habitat Connectivity Across European Highways (2002)

Sustainable Transportation Practices in Europe (2001)

Recycled Materials in European Highway Environments (1999)

European Intermodal Programs: Planning, Policy, and Technology (1999)

National Travel Surveys (1994)

Policy and Information

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery (2012)

Understanding the Policy and Program Structure of National and International Freight Corridor Programs in the European Union (2012)

Outdoor Advertising Control Practices in Australia, Europe, and Japan (2011)

Transportation Research Program Administration in Europe and Asia (2009)

Practices in Transportation Workforce Development (2003)

Intelligent Transportation Systems and Winter Operations in Japan (2003)

Emerging Models for Delivering Transportation Programs and Services (1999)

National Travel Surveys (1994)

Acquiring Highway Transportation Information From Abroad (1994)

International Guide to Highway Transportation Information (1994)

International Contract Administration Techniques for Quality Enhancement (1994)

European Intermodal Programs: Planning, Policy, and Technology (1994)

Operations

Freight Mobility and Intermodal Connectivity in China (2008)

Commercial Motor Vehicle Size and Weight Enforcement in Europe (2007)

Active Travel Management: The Next Step in Congestion Management (2007)

Managing Travel Demand: Applying European Perspectives to U.S. Practice (2006)

Traffic Incident Response Practices in Europe (2006)

Underground Transportation Systems in Europe: Safety, Operations, and Emergency Response (2006)

Superior Materials, Advanced Test Methods, and Specifications in Europe (2004)

Freight Transportation: The Latin American Market (2003)

Meeting 21st Century Challenges of System Performance Through Better Operations (2003)

Traveler Information Systems in Europe (2003)

Freight Transportation: The European Market (2002)

European Road Lighting Technologies (2001)

Methods and Procedures to Reduce Motorist Delays in European Work Zones (2000)

Innovative Traffic Control Technology and Practice in Europe (1999)

European Winter Service Technology (1998)

Traffic Management and Traveler Information Systems (1997)

European Traffic Monitoring (1997)

Highway/Commercial Vehicle Interaction (1996)

Winter Maintenance Technology and Practices-Learning from Abroad (1995)

Advanced Transportation Technology (1994)

Snowbreak Forest Book-Highway Snowstorm Countermeasure Manual (1990)

Infrastructure-General

Infrastructure Countermeasures to Mitigate Motorcyclist Crashes in Europe (2012)

Freeway Geometric Design for Active Traffic Management in Europe (2011)

Public-Private Partnerships for Highway Infrastructure: Capitalizing on International Experience (2009)

Audit Stewardship and Oversight of Large and Innovatively Funded Projects in Europe (2006)

Construction Management Practices in Canada and Europe (2005)

European Practices in Transportation Workforce Development (2003)

Contract Administration: Technology and Practice in Europe (2002)

European Road Lighting Technologies (2001)

Geometric Design Practices for European Roads (2001)

Geotechnical Engineering Practices in Canada and Europe (1999)

Geotechnology-Soil Nailing (1993)

Infrastructure-Pavements

Managing Pavements and Monitoring Performance: Best Practices in Australia, Europe, and New Zealand (2012)

Warm-Mix Asphalt: European Practice (2008)

Long-Life Concrete Pavements in Europe and Canada (2007)

Quiet Pavement Systems in Europe (2005)

Pavement Preservation Technology in France, South Africa, and Australia (2003)

Recycled Materials in European Highway Environments (1999)

South African Pavement and Other Highway Technologies and Practices (1997)

Highway/Commercial Vehicle Interaction (1996)

European Concrete Highways (1992)

European Asphalt Technology (1990)

Infrastructure-Bridges

Assuring Bridge Safety and Serviceability in Europe (2010)

Bridge Evaluation Quality Assurance in Europe (2008)

Prefabricated Bridge Elements and Systems in Japan and Europe (2005)

Bridge Preservation and Maintenance in Europe and South Africa (2005)

Performance of Concrete Segmental and Cable-Stayed Bridges in Europe (2001)

Steel Bridge Fabrication Technologies in Europe and Japan (2001)

European Practices for Bridge Scour and Stream Instability Countermeasures (1999)

Advanced Composites in Bridges in Europe and Japan (1997)

Asian Bridge Structures (1997)

Bridge Maintenance Coatings (1997)

Northumberland Strait Crossing Project (1996)

European Bridge Structures (1995)

All publications are available on the Internet at www.international.fhwa.dot.gov.

Chapter 2. Overview of Participating Agencies

Chapter 4. Agencies Help Elected and Appointed Officials be Better Stewards of Transportation Assets

Chapter 5. Agencies Focus on Outcomes and Operate as Service Providers

Chapter 6. Investment Priorities Are Known and Stakeholders Are Held Accountable for Their Actions

Chapter 7. Agencies Invest in Workforce Capacity Development and Succession Planning

Chapter 8. Efficiency and Value Drive Program Delivery Approaches

Chapter 9. Application of Key Findings in the United States

Chapter 10. Implementation Strategies, Dissemination, and Recommendations

Appendix B. Amplifying Questions

Appendix C. Host Country Contacts

Figure 1. Support provided by IPWEA

Figure 2. Rijkswaterstaat roles and responsibilities

Figure 3. Transport roles, responsibilities, and governance in England

Figure 4. Assets managed by Transport for London

Figure 5. Role of the long-term financial plan (IPWEA)

Figure 6. Illustration of methods of accounting for pavement assets by component (IPWEA)

Figure 7. Transport for London's framework

Figure 8. Strategic plan for building a better land transport system in New Zealand (NZTA)

Figure 9. Example of a two-coat seal (VicRoads)

Figure 10. Spending opportunities for the Highways Agency (England)

Figure 11. Highways Agency (England) spending opportunities on pavements

Figure 12. Yellow line used to brand asset management in the Netherlands

Figure 13. The three-legged stool used by Transport for London

Figure 14. Customer values identified by NZTA

Figure 16. Performance Audit Group's Annual Report

Figure 17. Transport for London's assessment of asset management capabilities

Figure 18. Illustration of asset management development plans for Transport for London

Figure 19. Tools and templates developed and distributed by IPWEA

Figure 20. Areas of focus for assessing internal capabilities

Figure 21. Six stages in the Highways Agency maintenance program

Table 1. Agencies participating in scan meetings

| AASHTO | American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials |

| DOT | Department of transportation |

| DPTI | Department of Planning, Transport, and Infrastructure |

| FHWA | Federal Highway Administration |

| GIS | Geographic information system |

| GPS | Government Policy Statement |

| IPWEA | Institute of Public Works Engineering Australia |

| IT | Information technology |

| ITS | Intelligent transportation system |

| KPI | Key performance indicator |

| LOS | Level of service |

| MMS | Maintenance management system |

| NCHRP | National Cooperative Highway Research Program |

| NZTA | New Zealand Transport Agency |

| NPRA | Norwegian Public Roads Administration |

| SLA | Service-level agreement |

| TRB | Transportation Research Board |

| TRL | Transport Research Laboratory |

| VicRoads | Roads Corporation of Victoria |

In the last few years, transportation agencies in the United States have seen the gap between available resources and investment needs widen. At the same time, demand on the infrastructure has been increasing and pressure from the U.S. Congress and State and local governments has been growing to preserve asset conditions and improve transparency and accountability in asset management. These factors have forced agency leaders to reevaluate how they manage assets and adopt innovative and cost-effective strategies for doing more with less.

Internationally, many countries have faced similar challenges and have responded with policies and programs to deal effectively with rising costs, declining revenues, and increasing demands for mobility and growth. They have developed cultures that support a performance-based management approach that accounts for the long-term financial implications associated with system expansion and views transportation decisions from a service-oriented rather than condition-based perspective. The lessons they have learned and the adjustments they have made could benefit transportation agencies in the United States that are considering new strategies for managing transportation assets.

Because pavements represent one of a transportation agency's largest investments, an international scan was conducted to investigate how countries internationally have improved the management of their pavements as they faced the challenges of decreased revenue, deteriorating conditions, and increased public demand for transportation services. The scan, which focused on pavements but was applicable to other assets, was cosponsored by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). Richard Tetreault, director of program development and chief engineer for the Vermont Agency of Transportation, and Butch Wlaschin, director of the FHWA Office of Asset Management, served as scan chairs. The scan took place in June 2011. Since the scan was completed, Congress has passed Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21), legislation that supports the use of performance-based programs such as those found internationally. The lessons learned in the evolution of practices used by the international scan participants will benefit the United States greatly as agencies respond to the accountability requirements outlined in MAP-21.

The scan focused on the following topic areas:

Although the scan team was investigating practices for managing pavements, most of the agencies it met with manage their pavement network in an asset management framework that considers factors such as strategic fit, effectiveness, efficiency, and risk in determining levels of investment for roads, waterways, rails, and other assets. These agencies operate in a culture in which the long-term implications of their decisions are understood and communicated to decisionmakers using strategic performance measures linked to tactical decisions. Therefore, many of the recommendations have an asset management focus that can be applied to pavements or other transportation infrastructure assets.

The transportation agencies and industry representatives selected for the scan had demonstrated the use of sound management principles and philosophies for managing their road (and other) assets. Even though the agencies ranged in size and population, each had implemented systematic processes for preserving and managing its road networks in response to external pressure to improve government efficiency and increase customer satisfaction, even during periods of tightened budgets. Without exception, each transportation agency outsourced most of its road maintenance and restoration activities in response to external pressure. Most incorporated a service-based approach that focused on stakeholder expectations in their road management practices.

The delegates traveled to Australia, England, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Sweden, where they met with representatives from the following agencies:

A separate visit to Adelaide, South Australia, was canceled because of air travel disruptions related to volcanic activity in Chile. South Australia's Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure (formerly the Department for Transport, Energy, and Infrastructure) submitted information to the scan team electronically, and the team conducted a Web conference with agency representatives in June 2012 to discuss their practices.

The economic situation the United States faces is similar to the economic situations many of the countries visited during the scan faced a number of years ago. These agencies, under pressure to improve government efficiency, responded by implementing systematic processes for maintaining the existing road network that emphasized reducing total maintenance and renewal costs over the life of pavement, managing future investment requirements, and minimizing agency risk. Although most of these agencies continue to face declining budgets, they have clearly defined priorities and investment strategies that have been accepted by stakeholders. The stakeholders also understand and accept the resulting impact of these decisions on the condition of the pavement network.

The timing of the scan proved to be extremely beneficial. The facilitated discussions provided the U.S. scan delegates with an opportunity to learn from agencies that had already experienced difficult financial situations and emerged with strong support for road maintenance and renewal among agency leadership, elected officials, and the general public. The challenges they faced and the lessons they learned while evolving their practices led to six key findings:

The scan team noted that although the scan focus was on pavement management, many of the findings relate to the broad application of a systematic process for managing pavements and other transportation assets under constrained conditions. Therefore, the scan findings are equally applicable to pavement management and asset management practitioners, as well as other transportation officials striving to obtain the greatest value possible for the funding levels available.

Pavement Management Is Integrated Into an Asset Management Culture That Supports Agency Business Processes and Long-Term

As in the United States, many of the transportation agencies included in the scan face outside pressure to be more efficient even as customer expectations increase and available funding decreases. In response to these pressures, several agencies have implemented systematic processes for maintaining their road networks, improving customer service, and maximizing the value for each dollar spent. These systematic processes focus on decisions that support a long-term vision for a sustainable pavement management program. The resulting framework is driven by an assessment of the whole-life costs of preserving the value of road assets and documenting the information in a long-term financial plan. In several of the countries visited, agencies must either fund the depreciation in the road network each year or account for the unfunded liability. The scan team also found more flexibility in programs than is typically observed in the United States. For instance, budgets at Transport for London are fixed over a multiyear period, providing flexibility in shifting projects from one year to the next. This feature was especially important to Transport for London so that construction projects were not scheduled during the 2012 Summer Olympics.

The scan team found that project priorities for road maintenance and renewal were based primarily on reducing agency risk and liability. This has led agencies to take very different approaches to managing their pavement networks. For example, the New Zealand Transport Agency has prioritized seven key state highway routes that have been designated roads of national significance for moving people and freight efficiently and safely between the five largest population centers. VicRoads, on the other hand, considers the deterioration of its low-volume sprayed-seal rural road network a catastrophic risk that would be more cost-prohibitive to address than the robust asphalt network in the urban area. Therefore, the preservation of the low-volume road network is a top priority. There was also evidence of multiyear financial plans to manage the road network that provide flexibility to move funding from one year to another and stability because the plans cannot easily be changed once they have been approved.

Agencies Help Elected and Appointed Officials Be

Some of the countries visited, especially Australia, had a strong use of long-term financial plans at the local level. These financial plans outline the strategies that will be used to effectively manage the road network and communicate risk and deferred liabilities for any underfunded maintenance and renewal activities. The long-term financial plans are developed collaboratively with government officials, who are held accountable for the way public funds are used to preserve the condition of infrastructure assets. As fiscal stewards, elected and appointed officials are responsible for the long-term viability and sustainability of the investment programs.

At several of the agencies the scan team met with, government officials are trained to better understand and honor their fiduciary responsibilities, which has led to support of transportation agency programs at all levels of government. This understanding of stewardship responsibilities was catalytic in supporting performance-based programs in several countries. This support has been especially important because transport agencies internationally do not have dedicated trust funds and must compete for funding.

Agencies Focus on Outcomes and Operate as Service Providers

The agencies that participated in the scan are moving toward a service-based approach for managing their road networks rather than a condition-based approach. Under this service-based approach, customer-driven priorities-such as safety, reliability of travel, comfort, and livability-are becoming the primary drivers for road maintenance and renewal actions. This change in philosophy is considered more meaningful than merely reporting on condition-based performance metrics. It has influenced the types of data collected and the performance targets used to drive the maintenance and renewal program. The New Zealand Transport Agency compared the philosophy to managing a utility. Under a more traditional model, a road may not have been available to carry an unusually heavy load because of existing road conditions. Under a service approach, the agency considers itself responsible for finding a way for the heavy vehicle to use the facility, representing a major shift in its philosophy and the way it approaches programming decisions. Rijkswaterstaat, the executive arm of the Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment in the Netherlands, bases decisions on the following key performance indicators, which focus almost entirely on service-oriented metrics:

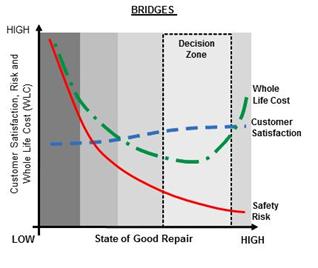

Transport for London considers risk, customer satisfaction, and cost as the three factors that must be balanced to provide an acceptable level of service. The relationship among these factors and the point at which a zone is established for making investment decisions differ based on the particular asset being investigated. For instance, because most highway users are less aware of bridge conditions than road conditions, risk and whole-life costs are the key decision drivers for that asset and the decision zone shifts to ensure that risks are suitably mitigated. For roadways, customer satisfaction is a much higher decision factor, so the decision zone reflects an effort to maintain it at a high level.

Investment Priorities Are Known and Stakeholders Are Held Accountable For Their Actions

As in the United States, most of the agencies participating in the scan face significant budget constraints and increasing demands to improve efficiency. In response, many have established clear priorities that emphasize service levels, while assessing the various options based on strategic fit, effectiveness, efficiency, and risk. As a result, these agencies assign the highest priority to maintaining and renewing the existing highway network rather than spending limited dollars on capital enhancements. In some cases, such as England's Highways Agency, the opportunities for expansion are limited because of space constraints. This places even more importance on the agency's emphasis on asset management as a way to maintain the value of the existing road network. The Finnish Transport Agency has developed long-term strategies aimed at maintaining the current condition of the main roads and letting the remainder of the system absorb the funding shortage. Priorities are typically conveyed in an asset management plan. For instance, Transport Scotland publishes a Road Asset Management Plan that sets objectives, targets, and required financial plans that support the government's targets for improving efficiency, reducing casualties, and lessening the impacts of climate change.

To help ensure the implementation of asset management programs, many agencies have established methods for holding agency personnel and contractors responsible for their actions through audits and contractual agreements. The audits the participating agencies used differed dramatically from those commonly used in the United States in important ways. In the United States, audits are used primarily to verify that a process was followed. In the countries participating in the scan, the audits are tied to the asset management plans and long-term financial plans to see how well the agencies carried out their plans. Transport Scotland programs are monitored and reported by the Performance Audit Group and reviewed and endorsed by Audit Scotland.

Agencies Invest in Workforce Capacity Development and

The agencies that have successfully navigated a paradigm shift in managing road networks have fostered a culture in which road maintenance and renewal costs are known and the long-term implications of decisions are understood and communicated by decisionmakers at various levels. As a result, these agencies have more mature asset management programs. This is evidenced by the branding of asset management at Rijkswaterstaat, which uses a yellow line as a symbol that connects pavement management with the management of bridges, traffic equipment, and people. The yellow line appears on all asset management materials and is featured prominently in the asset management office.

Without exception, the agencies that participated in the scan have committed to building and retaining internal capacity in asset management. As a result, they demonstrate strong investment in asset management capabilities that result in well-established, trained, and assimilated units in the organizations that all stakeholders, including executives and legislators, look to for information. This focus on training was especially evident in the tools and templates provided by the Institute of Public Works Engineering Australia, an association that supports the implementation of financially sustainable public works programs. As a result, the organization focused on the following actions to lay the framework for infrastructure sustainability:

In some cases, internal capacity building focused on regaining some of the internal capabilities lost when maintenance and renewal activities were contracted out. However, there is now a sense of urgency in replacing the competencies that were lost and building new capabilities that allow agency personnel to act as smart buyers of future maintenance and renewal services.

Efficiency and Value Drive Program Delivery Approaches

Most of the participating agencies contract out 100 percent of their pavement maintenance and renewal activities. According to the information the participants provided, these activities were privatized in response to pressure to reduce the debt load or improve efficiency during times of limited funding with a focus on maximizing the value of the investment. Over time, as agencies have gained experience with these types of contracts, contractual terms have evolved, as have the performance metrics that drive the contractor's performance.

The participating agencies were frank about the advantages and disadvantages of contracting for maintenance activities. For example, one advantage is that the cost of programs is known with certainty when the work is outsourced. These contracts have also helped several agencies improve government efficiency. However, several agencies indicated that they lost too much of their maintenance expertise and are in the process of rebuilding it. It has been a challenge to attract and retain skills in the agency because less engineering is being done internally. They also report that it has been difficult to find the right performance metrics and monopolies may form that limit competition. South Australia's Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure found that outsourcing its maintenance activities forced the organization to consider performance requirements from a road user perspective and to link the performance requirements to pavement condition characteristics. Although it was not recognized at the time, the discussions that took place focused informally on managing risk in terms of what risk level was considered acceptable and what was not.

Perhaps the most valuable lesson for the United States is that it takes time to develop contracts that work as planned. Transport Scotland, for example, is using its fourth generation of outsourcing contracts. The Finnish Transport Agency recommends that agencies considering privatized contracts do the following:

The agencies the team met with during the scan provided a wealth of information that will benefit the United States as its transportation agencies strive to find more effective methods of managing pavements and monitoring performance. The scan yielded a number of strategies for addressing the transportation issues the United States faces today:

The scan team included representatives from Federal, State, and local agencies to foster the implementation of the findings into the practices of transportation agencies throughout the United States. The representatives from FHWA and State highway agencies have identified strategies that can be implemented through FHWA programs, the National Cooperative Highway Research Program, and State initiatives. The local agency representative will work with FHWA's Local Technical Assistance Program to encourage adoption of the key findings at the city and county levels.

Based on the findings from the scan, the delegates identified the following implementation strategies to foster the use of systematic processes for managing pavements that support performance-based decisions to improve serviceability, accountability, and stewardship in the United States:

Encouraging use of long-term financial plans and providing technical assistance on how to develop them were the top implementation goals of the scan team. IPWEA has developed templates for use by local agencies in Australia, and the scan team would like to see similar templates, suitable for State agencies, developed in the United States. The financial plans would make agency funding transparent in the same way that publicly traded stocks are transparent: agencies would have to fund the depreciated value of their assets each year or account for this loss of value to the public as a liability.

Program assessments, termed audits by most of the agencies visited, close the loop between the work plan and the work conducted. The agencies depended on these program assessments to reduce political additions to their work plan because they are held accountable for work completed. The program assessment is a regular part of the business cycle and is a tool to keep the program on track and within budget.

In developing asset management plans, long-term financial plans, and program assessments, the countries found that new skills were required in their agencies. The financial plans require close communication between accountants familiar with depreciation accounting and engineers knowledgeable about maintaining the assets. Data are required and data collection and analysis are necessary for sound decisionmaking. Agencies in the United States will need this marriage of financial accounting and technical expertise, as well as the technology to support asset management.

Communication is an important first and ongoing step in implementing any research or scan findings. Through this executive summary, the scan report, and presentations to committees of AASHTO, FHWA, State and local agencies, and the Transportation Research Board, the scan participants are committed to bringing the value of the scan into U.S. practice.

Numerous publications report that the condition of highway pavements in the United States has declined in recent years.[1] Rising costs, increasing traffic, expansion, a worst-first approach to selecting capital projects, and the age of the infrastructure have all been cited as reasons for this deterioration. As a result of these factors, the gap between available resources and investment needs has widened. At the same time, there is growing pressure from the U.S. Congress and State and local governments to preserve asset conditions and improve transparency and accountability in asset management. These factors have forced agency leaders to reevaluate how they manage assets and adopt innovative and cost-effective strategies for doing more with less.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) have supported the use of a performance-based management approach as one strategy for managing assets effectively. While performance-based management approaches have been used in industrial and commercial applications in the United States and abroad for many years, the adoption of these practices at U.S. public agencies has been slow because of disconnects between actual infrastructure performance (conditions) and decisionmaking on financial investment in the highway network, particularly when looking at long-term economics. These disconnects appear to have been related to a lack of quality information, an inability to make meaningful projections linking investments to actual performance (impacting system credibility), and a perception that a business approach is not appropriate for public infrastructure. In addition, during eras of economic growth, such as the one the United States experienced in the mid-1990s, increasing revenues easily offset rising expenditures, which tended to mask the need to address long-term, sustainable solutions.

Internationally, countries such as Australia, England, New Zealand, and Scotland have faced similar challenges and have responded with policies and programs to effectively deal with rising costs, declining revenues, and increasing demands for mobility and growth. They have developed and fostered cultures that support a performance-based management approach that accounts for the long-term financial implications associated with system expansion and views transportation decisions from a service-oriented rather than a condition-based perspective. The lessons they have learned and the adjustments they have made could benefit transportation agencies in the United States that are considering new strategies for managing transportation assets.

To learn how others have successfully addressed these challenges and how the practices could be adapted in the United States, AASHTO and FHWA undertook an international scan. The scan focused on pavement management because pavements represent one of a transportation agency's largest investments. The scan took place in June 2011. Since the scan was completed, Congress has passed Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21), legislation that supports the use of performance-based programs such as those found internationally. The lessons learned in the evolution of practices used by the international scan participants will benefit the United States greatly as agencies to respond to the accountability requirements outlined in MAP-21.

The scan focused on the following topic areas:

Although the scan team was investigating practices for managing pavements, most of the agencies it met with manage their pavement network in an asset management framework that considers factors such as strategic fit, effectiveness, efficiency, and risk in determining levels of investment for roads, waterways, rails, and other assets. These agencies operate in a culture in which the long-term implications of their decisions are understood and communicated to decisionmakers using strategic performance measures linked to tactical decisions. Therefore, many of the recommendations have an asset management focus that can be applied to pavements or other transportation infrastructure assets.

The scan team was cochaired by Richard Tetreault, director of program development and chief engineer for the Vermont Agency of Transportation, and Butch Wlaschin, director of the Office of Asset Management for FHWA. They were joined by representatives of State and Federal highway agencies, academia, and private industry:

The transportation agencies and industry representatives selected for the scan had demonstrated the use of sound management principles and philosophies for managing their road (and other) assets. Even though the participants represented agencies that ranged in size and population, each had implemented systematic processes for preserving and managing its road networks in response to external pressure to improve government efficiency and increase customer satisfaction, even during periods of tightened budgets. Without exception, each transportation agency outsourced 100 percent its road maintenance and restoration activities in response to external pressure. Most incorporated a service-based approach that focused on stakeholder expectations in their road management practices.

The delegates traveled to Australia, England, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Sweden, where they met with representatives from the organizations in table 1.

Table 1. Agencies participating in scan meetings.

New Zealand |

Australia |

Sweden |

Netherlands |

England |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

A separate visit to Adelaide, South Australia, was canceled because of air travel disruptions related to volcanic activity in Chile. South Australia's Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure (formerly the Department for Transport, Energy, and Infrastructure) submitted information to the scan team electronically, and the team conducted a Web conference with agency representatives in June 2012 to discuss their practices.

Pavement Management Perspective and Terminology

Although the scan focus was on pavement management policies and practices, some of the agencies visited conduct pavement management in an asset management framework that considers factors such as strategic fit, effectiveness, efficiency, and risk in determining levels of investment for each asset.[2] These agencies operate in a culture in which the long-term implications of their decisions are understood and communicated to decisionmakers using strategic performance measures linked to tactical decisions. While the focus of the findings and recommendations is on the use of asset management principles and tools for managing pavements, it is understood that the same concepts have also been applied successfully to other transportation infrastructure assets.

These asset management principles and practices are integral to the development of the strategic goals and performance targets in these agencies. From that perspective, the practices identified during the scan are similar to the performance management functions that have been defined in the United States.

The scan team also identified differences in the terminology used in the United States and abroad. For example, U.S. transportation agencies commonly refer to pavement preservation as planned treatments that are applied to pavements in relatively good condition to restore or preserve their functional condition. In the countries visited during this scan, representatives referred to these types of noncapital activities as maintenance and renewal treatments. Capital improvements were often funded differently than maintenance and renewal activities and were not a major focus of the scan. Other differences in terminology are clarified in the report as necessary.

The economic situation the United States faces is similar to the economic situations many of the countries visited during the scan faced a number of years ago. These agencies, under pressure to improve government efficiency, responded by implementing systematic processes for maintaining the existing road network that emphasized reducing total maintenance and renewal costs over the life of pavement, managing future investment requirements, and minimizing agency risk. Although most of these agencies continue to face declining budgets, they have clearly defined priorities and investment strategies that have been accepted by stakeholders. The stakeholders also understand and accept the resulting impact of these decisions on the condition of the pavement network.

The timing of the scan proved to be extremely beneficial to the participants. The facilitated discussions provided an opportunity for the scan participants to learn from agencies that had already experienced difficult financial situations and emerged with strong support for road maintenance and renewal among agency leadership, elected officials, and the general public. The lessons learned from the technology exchange with these individuals led to six key findings:

The scan team noted that although the scan focus was on pavement management, many of the findings relate to the broad application of a systematic process for managing pavements and other transportation assets under constrained conditions. Therefore, the scan findings are equally applicable to pavement management and asset management practitioners, as well as other transportation officials striving to obtain the greatest value possible for the funding levels available.

The report is organized around the scan's key findings, with supporting information from the agencies visited during the scan in each chapter. Chapter 2 summarizes the key characteristics of the agencies visited. The supporting information on each of the key findings is presented in Chapters 3 through 8. Each chapter profiles some of the practices the team discovered during the scan and concludes with team members' key observations. Chapter 3 presents the steps the international agencies and associations have taken to build an asset management culture that supports each agency's business process and considers long-term financial responsibilities. Chapter 4 examines what agencies have done to help elected and appointed officials be better stewards of transportation assets. Chapter 5 presents information on the focus of many of the organizations as service providers. As discussed in this chapter, the emphasis on providing a service to the traveling public has had a significant impact on the types of performance measures used and the level of service provided. Chapter 6 examines the priorities the participating agencies have established and the strategies they use to hold stakeholders accountable. Chapter 7 addresses the investments the agencies have made in workforce development and succession planning, and Chapter 8 summarizes the program delivery mechanisms agencies have adopted to improve efficiency and value. Chapter 9 presents the lessons learned from the scan, and Chapter 10 describes recommended implementation activities to integrate some of the findings into the state of practice in the United States.

References to monetary amounts are reported in the country's own currency. Distance measurements are generally presented in metric units, but conversions to English units are included in the body of the report. No attempts were made to modify graphics provided by the participating agencies, even if different currencies or metric units were used.

The scan team met with representatives from 14 agencies in Australia, Europe, and New Zealand. The agencies were selected based on a desk scan of international practices used to manage pavements and monitor performance. To provide a context to better understand the references to organizational practices described in the report, this chapter summarizes the primary characteristics of the practices found in each agency.

New Zealand Transport Agency, Wellington, New Zealand

At the time of the scan, the New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA, www.nzta.govt.nz) had been in operation for about 3 years, having recently widened its scope by adding the rail network to its responsibilities. The State Highway Network includes 10,909 centerline kilometers (km) (6,779 miles (mi)) of road, which carry nearly 20,000 million vehicle-km per year. The agency's assets are reportedly worth about NZD23 billion, and annual investments total about NZD1.5 billion in state highways and about NZD650 million in local roads.[3] The Land Transport Management Act of 2003 is the legal framework for managing and funding land transport activities in New Zealand. The act provides for a Government Policy Statement (GPS), which sets the strategic direction for investment in the land transport section, allocates funding to activity classes in the National Land Transport Programme, highlights expected impacts from transport investments, and identifies roads of national significance that are priorities for completion. In addition, the GPS requires NZTA to use an integrated approach to transport planning that addresses all transport modes and land uses. Priorities incorporated into the agency's strategic plan include the following:

The agency provides advice to the Ministry of Transport, but considers itself to have primary responsibility for managing the transport system. Virtually all of its work is outsourced, including the design, maintenance, and management of the network. To retain competency in the agency, a Professional Service Group was developed to set performance requirements for contractors. Efforts are underway to ensure that critical infrastructure decisions receive national scrutiny and that the agency continues to be a knowledgeable client. Improvement projects and network management and maintenance are delivered through outsourced contracts managed from one of nine regional offices, but the strategic direction and priorities come from the national office in Wellington.

Department of Planning, Transport and

South Australia is comparable in size to Texas, but one of the major differences is the low density of population in the country. More than 70 percent of the population lives in Adelaide, so one of the agency's challenges is managing the long distances between small, rural towns. Because the state is home to manufacturing facilities, mining, agriculture, and forestry, the road network gets intensive freight use.

The Department of Planning, Transport, and Infrastructure (DPTI, www.dpti.sa.gov.au) maintains 12,650 centerline km (7,860 mi) of sealed roads and 10,000 km (6,214 mi) of unsealed roads. In addition, the agency is responsible for maintaining 1,500 bridges and major culverts, two tunnels, more than 700 signal systems, and 12 ferries. Local governments, considered the third tier of government in Australia, manage about 15,000 km (9,321 mi) of sealed roads and 60,000 km (37,282 mi) of unsealed roads. The national government and the state government represent the first and second tiers of government.

Funding for constructing and maintaining roads and bridges across South Australia is predominantly provided through the allocation of the State Highways Fund, which is administered under the Highways Act of 1926 and consists of money collected from drivers' license and motor vehicle registration fees. State funding is provided in 4-year estimates. In addition to state funding, which represents about 67 percent of the total funding, DPTI receives federal funding from the Australian government as part of a 5-year agreement. About 65 percent of the total funding is spent on pavements.

The agency's Strategic Infrastructure Plan for South Australia[4] outlines six strategic priorities for the agency:

Only the last of the six priorities focuses on asset management, although some of the other priorities are interconnected with asset management. For example, improvements in freight transport may lead to higher loads that may increase the rate at which the road network deteriorates. One of DPTI's challenges is to balance asset and pavement needs with broader transport issues within the available budgets. The focus on a broad range of transport priorities and the shift from internal provision of construction and maintenance activities to primarily external providers have transformed the organizational culture dramatically. As a result, the agency has had to focus more on establishing performance requirements from a customer's perspective.

VicRoads, Melbourne, Australia

Although Victoria is geographically one of the smallest areas of Australia, nearly a quarter of the Australian population lives in this state. Victoria is also home to about a third of the motor vehicles registered in Australia and a quarter of the country's freight tonnage. As the state road and traffic management authority for Victoria, the Roads Corporation of Victoria (VicRoads, www.vicroads.vic.gov.au/home) is responsible for maintaining 22,000 carriageway km (13,670 mi), or about 55,000 lane kilometers, of arterial road network, which includes 3,000 bridges. These assets have a depreciated value of AUD23 billion (about AUD38 billion replacement cost) and the annual program has a budget of about AUD1.9 billion. VicRoads employs about 3,100 professional, technical, and customer service staff in seven regions. The federal government is responsible for the road network that provides linkages benefiting the country as a whole, and local governments are responsible for the local road network using federal funds.

VicRoads has five principal aims that influence agency priorities:

Most of the arterial road network in Melbourne consists of flexible pavements built with crushed rock with an asphalt (bituminous concrete) surface that is typically 2 to 4 inches (51 to 102 millimeters) thick. Throughout the rest of the state, most of the roads are spray seals (also known as chip seals). These designs serve as a low-cost, all-weather system, so maintenance focuses on preventing the pavement structures from failing. Interventions are scheduled to address minor defects to keep the road safe, but also to prevent the minor defect from becoming more expensive to repair. Intermediate resurfacing of the routes is planned on a 13- to 14-year cycle, and restoration work is conducted on about 1 to 2 percent of the network a year if funding is sufficient to address other needs. Because of funding shortfalls in recent years, roads in poor condition are not being restored and VicRoads has elected to allow those roads to deteriorate further because there is no large difference in repair costs once the road is in bad condition. The agency has determined that its highest risk is losing the low-volume road network, so the majority of funding is targeted at preserving the condition of that network.

Most of the maintenance work is performed by contract forces based on broad parameters on the number of miles to be covered annually in each region. Each region prioritizes and selects the projects it will complete using a risk-based analysis that considers factors such as route use and traffic volumes.

Institute of Public Works Engineering Australia

The Institute of Public Works Engineering Australia (IPWEA, www.ipwea.org.au/home) is a professional association that provides its members with training, templates, guidance, and advocacy to support the delivery of public works and engineering services. A primary focus of IPWEA is on implementing financially sustainable public works programs. As a result, the organization focuses on the following actions to lay the framework for infrastructure sustainability:

This three-tier approach and the products that have been developed to support these efforts are reflected in figure 1.

Figure 1. Support provided by IPWEA.

The products include the International Infrastructure Management Manual, which establishes the framework for asset management planning activities, the Australian Infrastructure Financial Management Guidelines, which assists with the development of long-term financial plans, and Practice Notes on condition assessment, long-term financial planning, and asset management for small communities. In addition, IPWEA provides training, videos, and information exchange to support these efforts. IPWEA recently partnered with the Centre for Pavement Engineering Education to develop a graduate certificate program in infrastructure asset management that is accredited by the University of Tasmania. IPWEA strongly encourages agencies to just start using asset management principles and to improve the amount and quality of data over time.

Swedish Transport Administration, Stockholm, Sweden

The Swedish Transport Administration (www.trafikverket.se/om-trafikverket/andra-sprak/english-engelska) is responsible for the construction, operation, and maintenance of all state-owned roads and railways. The network includes nearly 100,000 km (62,137 mi) of government-owned roads and 12,000 km (7,456 mi) of railways. In addition to the state-maintained roads, there are about 41,000 km (25,476 mi) of municipal streets and roads and 76,100 km (47,286 mi) of private roads that are managed with a state grant. Its six districts include Stockholm, which is a single district. Funding for road maintenance is tight, with recent budgets at all-time lows for paved road maintenance, surface measurements, road markings, and drainage.

Norwegian Public Roads Administration, Oslo, Norway

The Norwegian Public Roads Administration (NPRA, www.regjeringen.no/en/dep/sd/about-the-ministry/subordinate-agencies-and-enterprises/norwegian-public-roads-administration.html?id=443412) was one of the transport agencies the scan team visited that is not multimodal. The agency focuses on the planning, construction, operation, and maintenance of the national and county road network, which includes 93,214 km of national roads, some of which are county roads (44,000 km (27,340 mi)) and some of which are considered to be municipal roads (38,515 km (23,932 mi)). The county provides funding for county roads, and NPRA administers the contracts for maintenance. Roads receive about NOK61 billion of the total budget for transport, which is estimated at NOK322 billion. Routine pavement maintenance and rehabilitation activities are performed by contractors under annual maintenance contracts. At the time of the visit, three contractors had responsibility for nearly 75 percent of the total amount awarded in contracts, and NPRA has noticed that costs are increasing each year. Current funding levels are adequate for stabilizing road conditions, but are not sufficient for improving them.

Finnish Transport Agency, Helsinki, Finland

is responsible for maintaining and managing state-owned roads, railways, and waterways. The agency spends about €609 million a year on basic road maintenance, which represents about 60 percent of the total funding available for infrastructure management. The road network consists of 78,200 km (48,591 mi) of public roads, which includes about 13,300 km (8,264 mi) of main roads, 765 km (475 mi) of motorways, and around 5,600 km (3,480 mi) of pedestrian and bicycle lanes, which are considered road equivalents. There are also about 14,600 bridges in the network.

The agency has nine regional offices, which are directed by the Ministry of Employment and the Economy. The Finnish Transport Agency is under the direction of the Ministry of Traffic and Communication. There have been challenges associated with coordinating the program because the central office (i.e., the Finnish Transport Agency) is directed by a different ministry than the users of the funds (i.e., the regional offices). Road improvements are funded entirely by the state budget with no revenue generated by taxes. Road maintenance strategies are outlined over a 4-year program, so pavement management strategies are somewhat stable over that time period.

Since 2004, the maintenance, rehabilitation, and operation of the road network have been entirely contracted out, with only traffic management performed in-house. Routine maintenance contracts are 5 to 7 years in length, but pavement maintenance and rehabilitation contracts are primarily annual contracts. There are about five main paving contractors, and most contractors are now required to provide 3-year guarantees on workmanship.

Danish Road Directorate, Copenhagen, Denmark

is a public authority under the direction of the Ministry of Transport. The directorate is responsible for the construction, extension, development, operation, and maintenance of the state road network. This network includes 3,788 km (2,356 mi), which represents about 5 percent of the entire public road network in Denmark. However, nearly 45 percent of all road traffic travels on these state roads. The Danish Road Directorate has been decentralized since 2009, and in 2012 three regional centers were established with responsibility for using the funds they are provided. All activities are contracted out and there are 4-year contracts for routine maintenance. Funding for road improvements is based 100 percent on taxes.

Rijkswaterstaat, Delft, Netherlands

is the executive agency responsible for the design, construction, maintenance, and management of the main national public works and waterway infrastructure on behalf of the new Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment (formerly known as the Ministry of Transport) and the State Secretary for Transport, Public Works, and Water Management. The organization has a budget of about €4 billion to €5 billion and employs about 9,000 employees. The road network includes 3,250 km (2,019 mi) of highways. The agency has 10 regional departments, which include 19 road districts and 16 water districts, and five specialized departments.

Rijkswaterstaat works to ensure that the Dutch communities have the following:

Asset management is ingrained in the organization's culture at all levels. Roles and responsibilities are clearly defined for the asset owner, asset manager, and service provider, as illustrated in figure 2. The asset owners are responsible for setting the future strategic goals for the network through a consideration of targets, risk, and cost. The asset manager develops tactical plans and investment strategies, and the service providers are responsible for operations, including renewal, expansion, and maintenance. In summary, the asset owners provide money, the asset manager provides knowledge, and the service provider provides the people needed to do the work. All of the maintenance activities are contracted out using 5- to 7-year contracts.

Figure 2. Rijkswaterstaat roles and responsibilities.

In addition to its recent name change, the agency reports that it is in transition and seeking new balance. Stakeholders, politicians, and the market all have different expectations for transport. Politicians want the cheapest approach, users want a system that is always available with no congestion, contractors want clarity on what needs to be achieved, and the public wants a safe place with dry feet. An organization that contracts out 100 percent of its maintenance and renewal activities, the agency relies on asset management to provide the knowledge needed to make decisions and the contract conditions to stimulate contractors to deliver optimal quality. The agency faces mandatory budget reductions of 20 percent, which will be addressed primarily through staff reductions. As a result of these changes, the representatives from Rijkswaterstaat stressed the importance of communication between technical and managerial levels.

Institute for Transport Sciences, Budapest, Hungary

According to representatives of the Institute for Transport Sciences (www.euromar-bridges.eu/index.php?id=kti), the Hungarian infrastructure includes 31,500 km (19,573 mi) of national public roads, 140,000 km (86,992 mi) of local (municipal) public roads, and 6,900 bridges. Since the 1990s, one of the primary focuses in the country has been to develop the motorway at a rate of about 30 to 50 km (19 to 31 mi) per year. Funding for the maintenance of the road network has not been adequate to preserve network conditions, with only about 0.7 to 0.8 percent of the gross value invested in the network each year. However, because of the addition of new motorway mileage each year, the average condition of the network is increasing, which masks the deterioration of the rest of the system. Therefore, it has been a challenge to effectively communicate needs.

To help estimate future needs, 60 pavement sections have been established to represent the performance of 14 different pavement families. These sections are monitored regularly to help establish relationships that can be modeled. These new models will replace the Markov Transition Probability Matrices that have been in use since the 1980s.

Highways Agency, London, England

Figure 3. Transport roles, responsibilities, and governance in England.

The Highways Agency (www.highways.gov.uk) is an executive agency of the Department for Transport responsible for operating, maintaining, and improving England's strategic road network on behalf of the Secretary of State for Transport. The Department for Transport sets policy and reports directly to Parliament and secures funds from the Treasury. This organizational structure is depicted in figure 3.

The national road network includes 7,200 km (4,474 mi) of roads that include motorways and single carriageway trunk roads with a total value of about £100 billion. This road network carries about a third of all the road traffic and nearly two-thirds of all heavy freight traffic in England. Each motorway carries between 30,000 and 200,000 vehicles per day and costs over £2 billion to manage each year. Demand for the facilities is growing each year, and increased competition for funding is expected to add to the challenges of managing this network. Funding for maintenance of the road network comes from public tax revenue. The agency was fortunate to get an additional £500 million for maintaining the road network for the past several years, but it expects funding to return to more typical levels in the coming years because the Department of Transport must compete with other social agencies for funds and the Highways Agency must compete with other groups in the Department of Transport for funds.

The Highways Agency's Strategic Plan for 2010-15 outlines the following strategic goals:

These goals are underpinned by a philosophy that the agency must be able to deliver more with less. The agency expects this to mean that it will have to eliminate some items that have been considered nice to have and coordinate efforts to obtain the information it needs. As a result, the agency has spent more time up front making sure it does the right thing on each project, plans each job correctly, and builds at a time that minimizes interruption to customers while ensuring that safety is not compromised. This focus on efficiency demands that employees and contractors have the skills to perform their duties, so the Highways Agency has established a plan to build internal capability through the following:

Roles, responsibilities, and governance are clearly identified, with the top tier of government (i.e., Parliament) passing legislation, the middle tier (i.e., Department for Transport) setting policy, and the bottom tier (i.e., Highways Agency) carrying out tactics. The Highways Agency Framework Document[6] is required by the Treasury to set out the relationship between the Department for Transport and the Highways Agency. The document was last reviewed in 2009 and is updated on a 5-year cycle.

The Treasury issues funding guidelines for the departments on a 4-year cycle.[7] Annual business plans are prepared by the Department for Transport and the Highways Agency[8] to document planned budget expenditures and expected performance measures. The annual report[9] prepared by the Highways Agency documents each year's achievements. The accounts are audited by the National Audit Office and reported to Parliament in terms of the outcomes met for the money received. As discussed in this report, these audits differ from audits conducted in the United States because they focus more on accomplishment of the achievements outlined in the plan than on verifying that procedures were followed.

Transport for London, London, England

Transport for London (www.tfl.gov.uk) was created in July 2000 as part of the Greater London Authority. The agency is accountable to an elected mayor and is the single integrated organization responsible for London's seven modes of transport. As shown in figure 4, the agency manages a wide range of assets, including carriageways, footways and cycle routes, structures, tunnels, street lighting, drainage, traffic signals, cameras, variable message signs, overheight vehicle detection systems, and green estate. The Transport for London road network consists of 580 km (360 mi) of London's most heavily traveled roads. Although this road network represents only 5 percent of the roads in London, it carries 30 percent of the total traffic and 50 percent of the city's freight traffic.

| Asset type | Quantity |

|---|---|

| Carriageway | 580 network km 2555 lane km |

| Footways & cycle routes | Oveer 1200km of footway 197km of dedicated cycle lanes |

| Structures | 513 bridges, 123 culverts, 696 retaining walls & 304 subways |

| Tunnels | 13 majors tunnels |

| Stree Lighting | Over 40,000 (of approx. 550,000 in London) |

| Drainage | Over 45,000 gullies |

| Traffic Signals | 2,471 units |

| Cameras | 2,471 units |

| Variable Message Signs | 164 units |

| Over height Vehicle Detection Systems | 54 units |

| Green Estate | Over 40,00 trees and over 700 acres of grass, trees & verges |

Figure 4. Assets managed by Transport for London.

The annual budget for capital renewal is about £80 million. About £160 million is spent on revenue maintenance. Broad goals and strategies for managing the transport system are outlined in the Mayor's Transport Strategy. 10] Several outcomes relate to asset management, such as the following:

In response, Transport for London developed its Highway Asset Management Framework, which conveys how it will deliver the outcomes outlined in the Mayor's Transport Strategy. The document includes a section on business management and another on highway asset management. The Highway Asset Management Framework links an investment strategy to the expected levels of service and evaluates performance to determine the value received for the money spent. The results of the analysis were first published in 2007 in the Transport for London Highway Asset Management Plan.[11] A new version of the document was expected to be published soon after the scan.

Transport for London has a long history of emphasizing the efficient and effective management of its existing assets and instituting means of reporting outcomes. One factor that has influenced the focus on managing existing assets is the limited space around London for growth to occur. As a result, there has been little pressure on the agency for expansion activities and asset management has become part of the day-to-day activities of the organization.

Transport Scotland, Glasgow, Scotland

Transport Scotland (www.transportscotland.gov.uk) is the national transport agency for Scotland, which is responsible for delivering the government's capital trunk road and rail investment program. In addition, the agency operates national concessionary travel, integrated ticketing schemes, and lifeline air and ferry services. The agency has more than 400 employees in Glasgow and manages a network of about 3,400 km (2,113 mi) of roads. The agency spends about £150 million on maintenance annually.

The primary focus of Transport Scotland is to invest transport funding in areas that support government priorities in crucial areas. The most recent corporate plan[12] describes the following delivery priorities:

Transport Scotland has contractual agreements with four operating companies to provide professional services associated with managing and maintaining the transport network. These companies administer major maintenance contracts and are required to tender any treatments that will exceed £250,000 in costs. A Performance Audit Group monitors the performance of the operating companies. Audit Scotland reviews and endorses the maintenance contracts. Transport Scotland makes a conscience effort to recruit and grow small- and medium-sized enterprises through these contracting arrangements, which use about 40 percent of the maintenance budget.

Transport Scotland has three teams: Asset Management, Network Maintenance, and Network Operations. Although the teams are independent, they work together to manage the transport network. The agency faces many challenges similar to organizations in the United States, including reduced budgets, government performance targets for organizational efficiency and road casualty reductions, and expectations to minimize negative impacts on the climate and the environment. It has a well-developed Road Asset Management Plan[13] that sets out the agency's objectives, targets, and required financial plans. However, current funding scenarios are not adequate to meet performance targets. Further complicating the issue are the government's targets to improve efficiency in all branches by 2 percent each year.

Transport Research Laboratory, Berkshire, United Kingdom

The Transport Research Laboratory (TRL, www.tri.co.uk/default.htm) is the United Kingdom's leading independent center for international transport research, providing advice on and solutions to transport issues. TRL has established partnerships with a number of government agencies in the United Kingdom, providing specialized transport expertise in several subject areas. Under this type of partnership, TRL is responsible for the development, operation, and accreditation of specialized equipment that collects pavement condition information at near-traffic speeds for England's Highways Agency. TRL performs similar processes for local authorities in the United Kingdom, including Transport for London. TRL manages and audits an extensive array of data collection equipment for the Highways Agency, including vehicles to collect surface distress, roughness, skid resistance, surface texture, structural condition, and construction thickness using ground-penetrating radar. Much of the information this equipment collects is stored in the Highways Agency's pavement management software for use in highway management activities. In addition to collecting data, TRL also serves as a consultant to government agencies in the United Kingdom. For instance, TRL has developed a whole-life cost analysis program for the Highways Agency and assists in developing and reporting key performance measures. In 2011-2012, about 45 percent (£20 million) of TRL's revenue was from work for government agencies in the United Kingdom.

As in the United States, many of the transportation agencies in the countries included in the scan face outside pressure to be more efficient, even as customer expectations increase and funding decreases. In response to these pressures, several agencies have implemented systematic processes for maintaining their road networks, improving customer service, and maximizing the value they receive for each dollar spent. These systematic processes focus on decisions that support a long-term vision for a sustainable pavement management program. The resulting framework is driven by assessing the whole-life costs of preserving the value of the road assets and documenting the information in a long-term financial plan. In several of the countries visited, agencies must either fund the depreciation in the road network each year or account for the unfunded liability. The scan team also found more flexibility in programs than typically observed in the United States. For example, budgets at Transport for London are fixed over a multiyear period, providing flexibility in shifting projects from one year to the next. This feature was especially important to Transport for London so that construction projects were not scheduled during the 2012 Summer Olympics.