U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

A key report for the New South Wales RTA is called Blueprint: 2008–2012 RTA Corporate Plan. It links the Australian state's aspirations with the day-to-day activities of its transportation agency.

Such reporting, which clearly demonstrates how transportation fits into larger societal goals, was evident in the scan of selected transportation agencies conducted in summer 2009. The scan on linking transportation performance and accountability provided substantial insight into how transportation agencies can incorporate broad national or state goals into their transportation performance management systems. This linkage of national and state goals to agency performance allows the agencies to illustrate how transportation serves larger societal goals and document accountability, performance, and need. The examples appear to hold clear lessons as the United States considers a national performance management system for its transportation programs. In this chapter, the underlying philosophy and strategy of the agencies' performance management systems are discussed.

A direct linkage between what society expects from its transportation agencies and what they achieve was strongly evident in the case study agencies for four reasons.

First, the national or state government articulated clear goals for the transportation system. Policy goals or expectations, such as economic development, safety, environmental sustainability, or best value for the money, were set as broad national or state transportation goals.

Second, the agencies negotiated service agreements that translated these broad goals into clearly articulated performance measures and targets. Third, the agencies' performance management systems reported their accomplishments in achieving the measures and targets. Fourth, the agencies continually refined their processes during more than a decade of performance management. Their officials cautioned that years of effort are needed to fully develop the performance management process.

The performance management systems set clear performance expectations and created transparency, not only on how the agencies perform but also on how their efforts contribute to broad national policy goals. In the agencies visited, it was apparent that transportation was considered a means to important societal ends. It also was apparent how effectively the agencies achieved those ends.

Despite the strong linkage between central government strategy and transportation agency execution, the scanning study did not find requirements that transportation agencies or regional planning organizations have long-term plans with specific projects lists, or fiscal constraint and air quality conformity requirements. The long-term plans the team saw tended to focus on policies, strategies, corridors, and general approaches to providing transportation, not on detailed long-term project plans. Plans that included specific, fiscally constrained lists of projects tended to be of shorter terms, such as 5 years. The team did not find analogies to the U.S. model, which requires fiscally constrained, 30-year, project specific plans.

The Australian state of New South Wales has more than 7 million people in a sprawling landscape 15 percent larger geographically than Texas. Its major city is Sydney, with its iconic bridge and opera house and a rapidly growing population.

At the time of the scanning study, the New South Wales State Plan included 34 priorities developed after an extensive public involvement process that began in 2006. The State Plan had several priorities that directly linked to the Business Plan and subsequent performance management system for the state highway agency, the New South Wales RTA. The strategic priorities for RTA were enumerated clearly in the State Plan and were included among other critical social objectives. The plan includes a goal-priority-target framework with the elements in table 1.

Building on the State Plan, RTA developed its own strategic document and framework, Blueprint: 2008–2012 RTA Corporate Plan. It noted, "The NSW State Plan is the key focus for the RTA's activities... The State Plan provides the vision for NSW for the next ten years." It notes that of the 34 priorities in the State Plan, RTA is the lead agency on the safer roads priority and is a partner agency for five others. "The Blueprint directs our organization in achieving these priorities," it stated.

Further specifying the agency's focus is the annual Results and Services Plan (RSP), a contract-like document negotiated between RTA and the central government ministry. The RSP is a confidential document that provides specifics on how the agency will spend its resources and direct its activities during the year to achieve the larger objectives set out in the State Plan and Blueprint. The RSP is a candid assessment that the central government can use to monitor agency progress. For public accountability, RTA produces its (annual report) corporate plan and budget papers, which lay out its short-term expenditures and expected accomplishments. The result of these documents is a comprehensive performance management approach to managing the agency. The framework started with the State Plan and cascaded throughout the organization down to the level of individual employees. New South Wales officials noted that within 6 months of being hired, an employee needs a personal performance plan that documents how he or she links to the agency's strategic priorities.

RTA officials noted that the evolution of the performance management framework created a direct link between what the public stated as its priorities and the activities carried out by the agency. They noted that in the original drafts of the state plan, transportation was not a prominent issue. However, during the extensive public involvement process, issues of congestion and infrastructure rose to prominence.

| State Focus | Transportation Agency Focus | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Area | Goal | Priorities | Targets |

| Delivering better service | An effective transport system | Increasing share of peak-hour journeys on a safe and reliable public transport system | Increase public transport share of trips made to and from Sydney's central business district to 75%. Increase the journeys to work in the Sydney metropolitan region by public transport to 25% by 2016. |

| Safer roads | Road fatalities continue to fall relative to distance traveled. | ||

| Growing prosperity across New South Wales | New South Wales: open for business | Maintain and invest in infrastructure | Maintain average growth of 4.6% in capital expenditure. |

| Environment for living | Practical environmental solutions | Cleaner air and progress on greenhouse gas emissions | Meet national air quality goals in New South Wales. |

| Cut greenhouse gas emissions by 60% by 2050. | |||

| Improved urban environments | Jobs closer to home | Increase the number of people who live within 30 minutes of a city or major center of public transport in metropolitan Sydney. | |

| Improve the efficiency of the road network | Maintain current travel speeds on Sydney's major road corridors despite increase in travel volumes. | ||

"Congestion and maintenance were not on the government radar because they didn't think they were on the public radar. It came up from the bottom and became state priorities (during the public involvement process). People were concerned about congestion and wanted roads maintained. They did not want a lot of new highways, but they did want congestion and maintenance addressed," said an RTA official. As a result, the priorities in the RTA Blueprint and Results and Services Plan can be directly traced to the priorities expressed by the state's taxpayers.

The central government of Sweden and its main transportation agency, SRA, also demonstrate clear linkages between the nation's overarching goals and how those goals are incorporated into the agency's transportation performance management system. SRA manages the road network for the nation of 9 million people spread across a landmass the size of California.

SRA demonstrates a robust performance management system that cascades national transportation performance goals throughout the agency and down to local governments. SRA receives few mandates or prescriptive performance requirements from its ministry, yet it still manages to translate the general guidance into detailed performance measures that direct the agency to achieve broad national goals. SRA expressed six broad goals to enable the transportation department to achieve the overall national objectives for transportation:

From those, SRA negotiated a comprehensive set of 18 objectives supported by more than 300 individual performance measures it developed for both internal and external reporting. Hard targets for those measures were negotiated between the agency and the ministry. For instance, its target was to reduce traffic fatalities by another 20 in 2009 as a short-term milestone toward a national vision of zero fatalities. It also targeted a department reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of 70,000 tons in 2009 as a short-term milestone toward reducing national carbon emissions. Both targets were negotiated with the central government. If SRA fails to achieve them, the performance is noted and a determination is made on what tactics are needed to achieve the goal in following years.

Even without prescriptive mandates, SRA has set clear goals on which it has achieved considerable progress in core business areas, including the following:

The Australian state of Victoria has a long-established performance management framework (figure 1) that has articulated goals for its transportation agencies.

Figure 1. The The Victorian planning and accountability cycle.

The performance management framework has evolved through several iterations of state plans in the southeastern Australian state of 5.2 million people. The state's highway agency, known as Vic Roads, and its transit agency, known as the Department of Transport, have long been recognized for their highly developed performance management systems.

The state's central government articulated a recent Victorian Transport Plan, which was developed by two state ministries, the Ministry for Public Transport and the Ministry for Roads and Ports. It significantly expanded the performance objectives for transportation beyond traditional highway condition performance measures. It specified six action priorities for the transportation agencies, including the following:

The strategic priorities of reshaping the transportation network in the face of overwhelming population growth created a profound impact on the agency's strategic goals. Its officials expressed an overriding focus on integrating land use and transportation, improving personal mobility, deemphasizing vehicle movement in lieu of moving people, and reducing transport's greenhouse gas emissions. As a result, the goals and performance metrics of the transportation agencies have evolved to include these priorities as well as traditional measures of highway condition and performance and organizational efficiency.

Victoria's transportation performance management system could be described as an advanced "posthighway era" or "sustainability era" transportation performance management system. Although its performance report retains its state-of-the- art reporting on highway conditions, it has advanced into additional areas of measuring sustainability and land use integration. In fact, the Department of Transport's secretary said he has concluded that land use planning and transportation planning are virtually the same. If his agency is to achieve the state's economic development and sustainability goals, it will need to measure its success by how well it links land use and transportation. The agency's performance management system is evolving to ensure the agency's transportation outcomes link to these evolving societal objectives.

The lightly populated but geographically diverse island nation of New Zealand is known in transportation circles for its advanced asset management and performance management processes. Those processes remain in place, but are undergoing a shift in priorities as a new government implements a new direction in national transport policy. The new government is strongly promoting improvements to national highway corridors as a component of a national economic development strategy. As a result, the transportation agency's performance management system is shifting rapidly to respond to and incorporate the new government objectives. The New Zealand experience in 2009 provided an example of how a longstanding performance management system shifts priorities to respond to changing social objectives.

New Zealand is a nation of only 4.2 million spread over two major islands that combined are the size of Great Britain. With its diverse terrain and relatively small population, the nation faces significant transportation challenges, both in sustaining its internal transportation network and shipping exports to international markets. NZTA was created in 2008 by merging Transit New Zealand, the highway agency, and Land Transport New Zealand, the funding and planning agency. Despite the country's small size, it has been cited frequently in international studies of best practices in asset management and safety.

NZTA is a crown entity administered by a board of up to eight apolitical professionals appointed by the minister of transport guided by State Services Commission guidelines. NZTA is headed by a chief executive, who reports to the board and has a team of 11 senior managers. This creates a dynamic in which the political priorities of the majority party set policy direction for the transportation agency, which is run on a day-to-day basis by longtime professional staff. One senior ministry official described the arrangement in sports terms. "The government gets to make the rules. But we have our players on the field and we can influence them so they know the game plan and are well coached. We in ministry have to help the government be a good coach."

The strategic framework begins with the periodic updating of the New Zealand Transport Strategy, a long-range strategic plan with a horizon of up to 30 years (figure 2). When new government elections are held every 3 years, the parliamentary majority forms a government and adopts a Government Policy Statement, which spells out its detailed transportation policies and associated spending priorities for the next 6 years and outlines a further 4-year forecast for a total of 10 years. However, the statement must be updated every 3 years. The NZTA Investment and Revenue Strategy is developed from both the government's policies and the long-range agency strategic plan. The strategy provides a direct link between the Government Policy Statement and the National Land Transport Programme and demonstrates how the program carries out government priorities.

Figure 2. New Zealand's performance management steps.

An additional intermediate link is the Statement of Intent, a forward-looking 3-year plan updated annually that spells out how the agency will link its efforts with the Government Policy Statement. The Statement of Intent is similar to a business plan in that it sets the agency's budgets and priorities and demonstrates how it intends to make progress on the Government Policy Statement priorities over 10 years.

Next the agency updates the National Land Transport Programme (NLTP), which sets out the allocation of funds to transport activities for the next 3 years. It is similar to a Transportation Improvement Program in the United States. The NLTP lists the activities and projects to be funded. The NZTA program includes projects it will manage as well as the allocations to local governments for projects and maintenance activities they will develop. The NLTP also describes the significant issues facing land transport and includes a 10-year forecast of anticipated revenues and expenditures. From the funding provided by NZTA and the money raised by local authorities through rates, the regions develop transport programs, which include projects and maintenance activities sponsored by the local governments. Local authorities develop 10-year plans called Long-Term Council Community Plans, which must be updated every 3 years. These set the levels of service for funding. Projects for financial assistance must be assessed as part of the Regional Land Transport Programme, which is guided by the Regional Land Transport Strategy (RLTS.) The RLTS is often guided by regional growth management, economic development, and spatial strategies. Substantial input on local programs and local asset management practices come in the form of legally required asset management practices, which NZTA evaluates.

NZTA and its predecessor agencies conclude their performance management cycle with annual reports. The new merged agency, NZTA, produced its first annual report for the financial year 2008, ending June 30, 2009. The report had extensive metrics to document agency performance in achieving the Statement of Intent and illustrate how that performance linked to larger governmental goals.

For the past decade, the British have evolved a performance management system in which the central government's approach shifted from setting many precise performance targets for its transportation agencies to setting broader, more general goals. National, regional, and local transportation agencies develop their own metrics and business plans to carry out the national goals. Regular reporting of results provides feedback to the central government on how effectively its priorities are being achieved by the complex network of central, regional, and local transportation agencies, as well as by the many private contractors who operate in the highly privatized British transportation system.

The performance management framework applies to the transportation network in England, with separate governance structures in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

The main British transportation agency is the Department for Transport, which oversees both HA and monitors the private contractors who operate the nation's rail passenger system. HA improves, operates, and maintains strategic roads for the 51 million people in England, who live in a 50,000-square-mi (129,499-square-km) nation about the size of Alabama.

The British governance structure is substantially different from that in the United States. This may reflect the Next Step movement in the 1980s and privatization initiatives in the transportation sector in the 1980s and 1990s.

The day-to-day responsibility for strategic roads lies with HA, a semiautonomous arm of the Department for Transport with its own board and chief executive. The relationship between HA and the Department for Transport is formalized. The department approves and sets HA's budget and agrees to its business plan and targets. HA is responsible for delivery. In delivering some of its functions, HA relies on contracts with external organizations and commercial companies. For example, routine maintenance is provided by private companies under contracts let by competitive tender.

As a result of privatization, passenger rail services are also provided by private companies, in this case operating franchises and contracting directly with the Department for Transport. Service levels and certain types of fares are controlled by the Department for Transport, with companies either paying a premium or receiving a subsidy (contracts are let after a competition). In this case remedial action, including financial penalties, may be taken against rail operators that fail to provide acceptable services.

The Department for Transport operates under five broad strategic goals that it negotiates with the central government:

From those five flow an extensive performance management structure that measures dozens of aspects of British transportation performance. Most individual targets are not set by the central government, but are developed by the transportation agencies for measuring success on achieving the national goals. Top-level targets are approved by ministers. The implementing agencies include HA and various regional and local agencies that receive government transportation funds.

From the Department for Transport strategic goals flow the objectives for HA, which has an aim of "safe roads, reliable journeys, informed travelers." HA's objectives are the following:

Figure 3. Great Britain's performance management approach spurred increased efforts to manage congestion.

The Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads displays another well-articulated strategic management framework in which broad, catalytic state goals flow through a performance management process in the transportation agency down to the individual project and activity level. Queensland is Australia's most rapidly growing state, with a population of 4.2 million spread across a huge landmass twice the size of Texas. Queensland is a diverse state that includes the upscale Miami Beach-like Gold Coast, the Great Barrier Reef, and thousands of square miles of sparsely populated interior.

The state and municipal governments have been coping with significant urban population growth and have invested heavily in an integrated, multimodal transportation network. The emphasis on integration extended to a recent merger of Queensland Transport, the former transit agency, with the Queensland Department of Main Roads to form the Department of Transport and Main Roads.

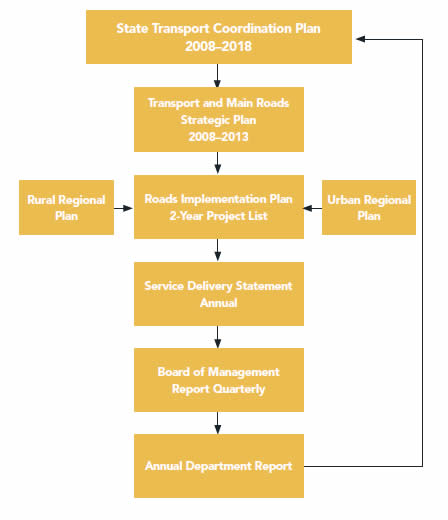

For more than a decade, the two agencies operated under a state strategic transportation plan. In 2008, the Queensland minister for transport, trade, employment, and industrial relations and the minister for main roads and local government jointly developed the updated state transportation plan known as the Transport Coordination Plan for Queensland (figure 4, see next page). This plan set the strategic direction for both the highway and transit agencies before and after their merger. It expressed the strategic context and challenges facing the state. The state is coping with rapid growth, high congestion, automobile dependency, environmental changes, high community expectations, a threatened quality of life, and diverse regions with differing transportation needs. The Transport Coordination Plan laid out 10 strategic objectives for the transportation agencies:

Figure 4. The Queensland transportation agencies have a well-articulated performance management system.

The Department of Transport and Main Roads converts these broad goals into an increasingly specific set of reports and metrics by which it can assess-and be measured-on how well it is implementing the state government's overall transportation aspirations, including the following:

The scan team's overall impression after reviewing the Queensland process and interviewing its officials was that the state has created strong linkages between its strategic goals and the day-to-day activities of its transportation agencies.

Despite the greater linkage of national goals to agency activities, the central governments mandated few explicit and quantitative national transportation targets for the transportation agencies. It appeared that as the agencies' performance management systems matured, the central government shifted from insisting on precise performance targets to monitoring long-term system trends.

The scan team seldom found one level of government mandating the performance of another. Rather, the service-level agreements or other negotiated documents between the central government and the transportation agency were used to define performance measures and targets for which the transportation agency was held accountable. The service-level agreements communicated priorities and clarified outcomes while allowing each state or region to negotiate measures and priorities important to its unique circumstances. These negotiations were supported by extensive data collection that showed trends in systemwide performance. Negotiations between the agencies and their central governments were fluid and continuous. Flexibility in adopting strategies and targets was key, particularly in major cities with unique transportation needs and solutions.

The combination of national goals cascading into state or regional performance measures appeared to create a greater emphasis on outcomes than on process. Results, not process, appeared to be what was closely monitored.

The New Zealand system was typical of what the scan team found in its study. A Government Policy Statement spells out broad objectives for transportation. The transportation agency produces a Revenue Investment Strategy and a Statement of Intent to articulate how it intends to invest in transport and achieve the central government's broad transportation goals.

"This structure requires the government to say, ‘This is what we want you to achieve,'" said a New Zealand official. "One of the critical points is a mechanism for government to articulate its policies and for the agency to have a dialog about those priorities."

The 2009 New Zealand Government Policy Statement for transportation includes no hard, numeric targets. The only numbers in the document are for budget appropriations — minimum and maximum investment ranges for each investment category. However, it provides clear strategic direction on what it wants from NZTA.

"The government's priority for its investment in land transport is to increase economic productivity and growth in New Zealand," said the Government Policy Statement. "Quality land transport infrastructure and services are an essential part of a robust economy. They enable people and businesses to access employment and markets throughout the country and link them to international markets through the nation's ports and airports. Investing in high-quality infrastructure projects that support the efficient movement of freight and people is critical."

The Government Policy Statement lists seven national corridors as part of a Roads of National Significance network. It directs NZTA to focus resources on these routes to achieve economic growth and productivity. It designates the routes as the nation's most important and says they require significant investment to reduce congestion, improve safety, and support economic growth.

Two important exceptions to the rule that the central government did not set hard targets were in safety and greenhouse gas emission reductions.

"In pursuing economic growth and productivity, the government also expects to see progress on other objectives. The Land Transport Management Act 2003 requires the Government Policy Statement to contribute to achieving an affordable, integrated, safe, responsive and sustainable land transport system, and also to each of the following:

The following are other impacts the Government Policy Statement sets for the agency:

After the Government Policy Statement is published, the agency develops its Revenue and Investment Strategy and negotiates its Statement of Intent with the government, setting out what it will achieve during the next 3 financial years. The Statement of Intent explains how it will spend the government's resources to achieve its desired ends.

"The government has provided clear expectations for service delivery for the financial year 2009-2010 and out-years," stated NZTA's Statement of Intent. "This clarity has enabled the organization to focus on what matters most, and to develop five business priorities to ensure organizational resources, behaviours and decisions give effect to the government's intent. Over the coming three financial years there will be a particular focus on improving road safety, improving the effectiveness of public transport, improving the efficiency of freight movements, planning for and delivering roads of national significance, and improving customer service and reducing compliance costs."

The Statement of Intent sets comprehensive targets, such as achieving 90 percent of all project development milestones on the Roads of National Significance, achieving specific travel time goals on major routes, and receiving a 75 percent satisfaction rating in surveys of road users. The Statement of Intent includes 64 such comprehensive performance measures. Most are cumulative, programmatic measures, such as achieving a certain level of pavement condition across the entire network. Listed with each group of measures is the accompanying budget expenditures. This pairing allows the agency to link its budget inputs with its desired outputs and illustrate how those outputs achieve the government's objectives.

As a result, the New Zealand system produces clear measures of expenditure and accomplishment, but without a set of rigid, centrally mandated targets. Instead, the targets are negotiated between the political minister and the professional staff of the transportation agency.

Similar to the Statements of Intent in New Zealand are the Public Service Agreements in Great Britain. The Public Service Agreement is a widely used device to set goals between units of government (figure 5). The Department for Transport has a Public Service Agreement with Treasury to specify the department's performance goals for a budget cycle. Likewise, the department has developed agreements with local governments for 10 major urban areas with accompanying measures that underpin the indicators in its own Public Service Agreement.

Figure 5. The British rely on service agreements to implement government goals.

The British experience over the past 12 years has been movement toward negotiated agreements and away from a large number of mandated targets. The number of measures, targets, and mandates has steadily fallen and the process has evolved from a hierarchical, mandate-driven one to a more collaborative one. The British experience provides a cautionary tale on the use of centralized performance metrics. In the initial stages of British performance management in the 1990s, the number of metrics proliferated to a cumbersome level. Central government imposed an estimated 2,000 metrics on local government and about 600 across national departments. From 2000 to 2009, those metrics were steadily consolidated to 188 for local government and 30 across national departments. The Department for Transport now primarily operates under one Public Service Agreement with underlying indicators.

Not only have the measures on local governments fallen from 2,000 to 198, but local governments only have to set targets for up to 35 of those measures, along with 18 mandatory targets for education and children's services. The local governments agree on up to 35 targets, based on which improvements are most important to the local community. Local governments report the values of the other measures, but they are used only as indicators of condition or trends, not specific targets that have to be met.

British transportation officials emphasized that the dialogue between the various levels of government in negotiating and monitoring the Public Service Agreements was as important—or perhaps more important—than the setting of the hard performance targets. The setting of targets and the continuous dialogue on how to best achieve them resulted in increased consensus, alignment, and understanding between the central government and the transportation agencies it funds.

British officials said the current system began in 1998 when a process called the Comprehensive Spending Review was initiated. In that process, the central parliamentary government prepared 3-year spending plans and developed Public Service Agreements with each national department on its expenditures for the priorities it would pursue. They cited the following as strengths of their system:

An example of a key Public Service Agreement is Delivery Agreement 5: “Deliver reliable and efficient transport networks that support economic growth.” The Treasury is the government entity that works on behalf of the prime minister to negotiate the Public Service Agreement with the Department for Transport. It set a broad government goal of having “reliable and efficient transport networks that support economic growth.” From that goal, the government and the Department for Transport negotiated the following indicators (not hard targets):

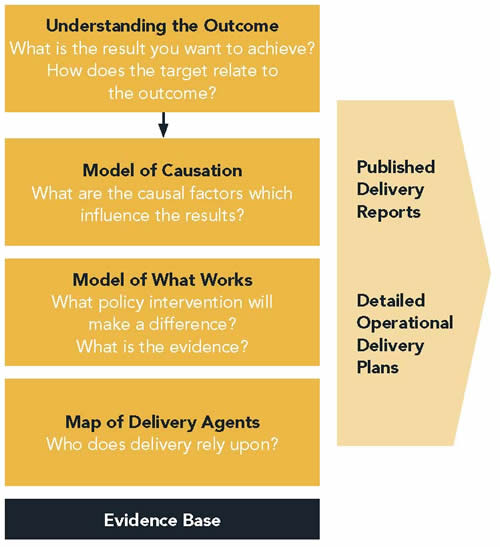

SRA operates under a similar framework in which Parliament issues broad, qualitative goals to the transportation agency in its annual budget process (figure 6). These directives contain few metrics and the entire document may be less than 10 pages of general discussion on what Parliament wants SRA to focus on.

Figure 6. The Swedish system translates broad government goals into agency action plans.

SRA incorporates this periodic guidance into two key documents. One is SRA's Strategic Plan, which includes an intermediate horizon of 10 years and key priorities articulated by the government. On a short-term basis, SRA produces a much more detailed Operational Plan and a short-range document that focuses on activities in the upcoming budget cycle. The Operational Plan is influenced by government priorities, parliamentary direction, and the extensive public outreach process Sweden deploys. In a nation of 9 million people, 9,000 are annually surveyed on their satisfaction with a number of basic issues. These include traditional issues, such as pavement smoothness, winter snow and ice control, and how promptly they received a driver's license from the licensing bureau. But other measures are much more personal. SRA found that 66 percent of parents report their children have a safe route to school, while up to 10 percent believe their child's route is very unsafe. The results of these surveys, as well as a customer satisfaction index and input from Customer Councils, are combined with parliamentary direction to influence the Operational Plan.

Directly from the Operational Plan flows a Balanced Scorecard reporting process. The Balanced Scorecard reporting is scalable throughout the agency. A summary report rolls up agency performance. However, the performance of individual units or districts also can be reported. All results are on an agency Web network and are shared with the government ministries.

SRA officials said, however, that the most valuable part of their reporting process–at least in communicating with the central government–are the frequent update meetings they hold with budget officials in the ministries. SRA must provide four mandatory update reports on its Operational Plan and Balanced Scorecard accomplishments. However, much more frequent and informal communication occurs, providing continuous opportunities for budget officials to understand the progress, challenges, and issues confronting SRA.

Similar to the U.K. Public Service Agreements, the New South Wales RTA generates a Results and Services Plan and a Budget Paper that specify how it will spend its budget, what priorities it has, what targets it expects to meet, and what activities it seeks to accomplish during the budget period. Senior agency officials described the Results and Services Plan as a contract-like document that specifies how they will invest AUD4.4 billion in state and federal funds.

While the Results and Services Plan is a private document given to the state government, the two annual Budget Papers are public documents that explain spending to achieve government transport priorities (figure 7). One is a 30-page document that lists major budget expenditures, general accomplishments, areas of policy emphasis, the status of major projects, and key indicators of performance proposed by the agency. The other is a much longer Infrastructure Statement that addresses investments in sustaining and improving all forms of the state infrastructure, including transportation. These two documents reflect the parallel nature of the New South Wales budgeting process and accountability process. One aspect focuses on shorter term operations, while the other focuses on longer term total asset management priorities.

Figure 7. New South Wales translates government strategy into measureable outputs.

Among the operational performance indicators it reports are the following:

Agency officials said the targets in the Results and Services Plan, Budget Papers, and total asset management plan are realistic ones they set after negotiating with state government officials. "Imposing targets is likely to be ineffective and we prefer the carrot to the stick. If you set an imposed target, you will get resistance constantly. We say, 'you give us the target and we will work with you on whether it is the right target,'" is how one agency executive described the target-setting process.

Although setting reasonable targets involves negotiation, once targets are set clear processes are in place to ensure progress toward achieving them. A monthly performance meeting between agency managers and the chief executive officer focuses on progress on accomplishing the agency goals, targets, and business plan. They use an internal dashboard for each measure and only spend time talking about areas in red, which are out of tolerance. They limit agency executives to a two-sentence explanation during the fast-paced meeting to explain how they will get performance back on target.

Periodic oversight from what are called the Central Agencies further enhances accountability. The New South Wales Treasury and the Auditor General conduct periodic performance audits and oversight functions to ensure achievement of agency performance goals.

Agency officials described the budgeting process as a "results budget" that compels the agency to think about important societal outcomes and decide what the public wants from government services. Instead of merely processing driver's licenses, officials think about producing more competent drivers. Instead of building highways, they consider whether they provide reliable journeys or high-performing highway assets. They described the results budgeting process as an ever-progressing evolution to link changing societal needs with the agency's performance. An official said the agency wants metrics that contribute to a performance culture.

The New South Wales budget and performance management processes are closely linked to a long-term total asset management approach that is legislatively mandated throughout the state. The New South Wales Treasury oversees a statewide total asset management approach that applies to all state assets, including highways, state buildings, information technology networks, water systems, and other public assets. The New South Wales RTA manages an extensive Total Asset Management Manual that covers all phases of an asset's life cycle, from planning through retirement. This manual drives a total asset management plan, which is closely linked to the budgeting and performance process.

The agency plans a 10-year transportation asset management strategy operated in parallel with the 3-year Results and Services Plan. The intention is to keep the shorter term political budgeting process linked to long-term highway asset management needs. As described later in this report, the syncing of the budget and asset management processes has not resulted in the total amount of investment that the agency identified. However, the linkage has clearly illustrated long-term asset needs as part of the short-term budgeting cycle.

As in other agencies, New South Wales transportation officials said the dialogue and increased understanding that comes from the negotiation and reporting process is an important benefit of the integrated performance management budgeting approach.

Similar to the New South Wales RTA, the Victoria Department of Transport produces voluminous accountability documents that set out detailed aspirations based on state and regional goals. Its short-term priorities are strongly influenced by the state's focus on coping with rising congestion and environmental impacts caused by the substantial growth the region is experiencing. The short-term objectives the Department of Transport pursues stem directly from the long-term state goals to further integrate transportation with land use, offer more transportation choices, reduce emissions, and improve the overall sustainability of the region. Because of the many similarities to the process used in New South Wales, the Victoria process of setting short-term targets will not be described in detail. One difference is that it appeared the focus on land use and transportation integration is even more pronounced in Victoria.

Victoria officials describe how their outcome-driven approach has influenced even their accounting process. They said the state moved from cash-based accounting to accrual-based accounting as part of an effort to clearly link expenditures with outcomes. They said the historical approach to public sector financial management in Victoria and other jurisdictions was to apply cash budgeting and reporting. Management of services was based on programs with a focus on inputs to the government instead of outcomes for the public. Department assets and liabilities were not financially recognized in annual reports, and the overhead costs of leave and pensions were reported by the central Department of Taxation and Finance, not the transportation agencies. By moving to accrual-based accounting, the future liability of accumulated pensions, leave, and infrastructure needs can be recognized on the transportation department's books.

As a result, departmental services could not be fully costed on a competitive and neutral basis with other agencies or the private sector. Further, the input focus did not promote achievement of actual service delivery outputs. A reform process in the 1990s instituted a much more outcome-focused budgeting process that fully accounted for all agency costs to provide services, including all department overhead.

| Victoria DOT 3-Year Priorities | |

|---|---|

| Priorities | Strategies |

| Integrate transport and land use planning | Shape Melbourne and regional Victoria to reduce the amount and distance of travel. |

| Ensure legislative and governance arrangements support emerging transport challenges. | |

| Improve long-term planning and secure strategic reservations. | |

| Support the Victorian economy with an effective and resilient transport system | Increase the capacity of the transport system. |

| Maximize the operation and use of the existing transport system. | |

| Improve the accessibility and service quality of the transport system and address transport disadvantage. | |

| Ensure safety for all transport users | |

| Ensure safer roads, roadsides, vehicles, and users. | |

| Ensure safer public transport services and create personal safety of public transport users. | |

| Ensure safety and security of freight transport. | |

| Ensure safer waterways. | |

| Improve the sustainability of Victorian transport | |

| Support mode shift to more sustainable travel modes. | |

| Improve the environmental efficiency of transport activity and the transport fleet. | |

| Mitigate the impact of transport activities and adapt to the effects of climate change. | |

| Build a collaborative and effective organization | |

| Transform the culture of the department to maximize performance on behalf of the community | |

| Improve program development and delivery and risk management. | |

| Communicate effectively with the community, industry, and other government agencies. | |

As a result of the budget and programming reforms, the Victoria Department of Transport now expresses more of its programs in terms of outcomes to the public and alignment to long-term goals.

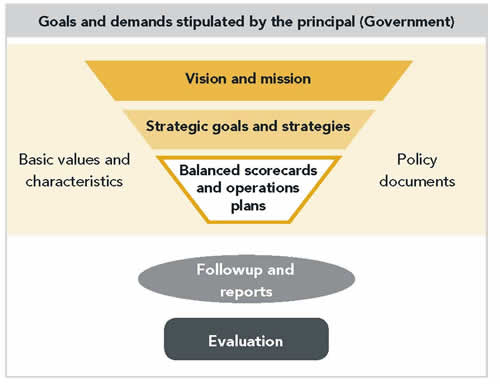

As emphasized in the other agency examples, the state government has not imposed hard targets on the Victoria Department of Transport. However, its performance management and performance budgeting processes have evolved consistently so that they now link their programs to outcomes that support broader government objectives (figure 8). Agency officials said their plan aligns performance measures for each priority in the state plan and state budget priorities.

Its 3-year and annual reports include achievements, such as the opening of a new section of highway. It includes outputs, such as the miles of road that meet pavement smoothness goals. It also reports outcomes, such as an improvement in travel time as a result of the new projects.

Figure 8. Victoria's performance pyramid illustrates linkages between broad government goals and agency services.

| << Previous | Contents | Next >> |