U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

In Australia, the study team perceived a strong emphasis on entrepreneurship and the application of sound business principles to department of transportation (DOT) operations, including right-of-way acquisition and management and utility coordination. Examples of business strategies include the following:

An emphasis on effective communications, appropriate performance measurement (that focuses on measuring what matters), and customer satisfaction (through an institutional environment and business culture that fosters a good relationship between the DOT and the public and other transportation stakeholders) has resulted in some of the agencies visited being ranked among the highest in their states on public satisfaction with their performance.

Through a consensus process, the Australian Transport Council developed a Transport System Management Framework (figure 3) that focuses on strategic plan delivery and review, strategic alignment of activities, sound justification of activities, identification of future transportation needs, and definition of activities consistent with future plans.(6) A key component of the framework is the emphasis on iterative feedback throughout the lifetime of a transportation facility, including the use of performance measures to determine the effectiveness of initiatives, programs, and strategies, enabling a direct link between the operation and management of a transportation facility and overall planning activities.

Click image to enlarge

Figure 3. Australia Transport System Management Framework.(6)

Individual states have processes consistent with the national framework. For example, figure 4 shows the project initiation process that South Australia's DTEI follows for developing and implementing transportation projects. This process relies heavily on the preparation of certain critical documents, such as a risk assessment and a business case to provide adequate justification for projects. The risk management approach extends to the assessment of risks and cost contingencies associated with property acquisition and relocation of utilities. Queensland's road planning framework (figure 5) also relies heavily on strategic planning, resource management, performance measurement, evaluation, and continuous improvement.

Click image to enlarge

Figure 4. DTEI's project initiation process.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 5. Queensland's road planning framework.

In Canada, substantial differences exist between Alberta and Ontario on transportation planning challenges, practices, and strategies for project development. Alberta's energy sector is largely responsible for the large budget surpluses the province has enjoyed in recent years. The budget surpluses give the province considerable flexibility in developing and delivering transportation projects. However, rapid growth in population and economic activity is putting considerable pressure on Alberta's ability to respond to public needs and requirements in a timely fashion. In contrast, Ontario has a mature manufacturing economy, which imposes significant limitations on the province's ability to deliver needed transportation projects.

Before 1995, nine commissions handled land use planning in Alberta. In 1995, in response to requests from local jurisdictions for more local control, municipalities were given greater authority for land use decisions (Alberta has about 300 municipalities, 200 of which are in the southern region). Although well intentioned, more local control resulted in practices that were not necessarily consistent or appropriate (e.g., allowing disproportionately massive developments at certain locations, charging much lower development permit fees at some locations than at other locations, and requesting highway interchanges at locations that were not appropriate from a network connectivity perspective). Alberta Transportation is addressing this issue by tying the provincial contribution to locally requested projects to the number of years into the future the department was already considering those projects for construction (90 percent for 1 year, 80 percent for 2 years, 70 percent for 3 years, and 0 to 60 percent for more than 3 years).(7) For Alberta Transportation to consider a cost-sharing plan, the project must be included in the department's business plan.

Recently, the government of Alberta developed a new land use framework for the province that will consolidate land use planning into six planning regions.(8) Strategies for land use planning consolidation include creating a cabinet-level overseeing committee; establishing regional advisory councils; developing a cumulative effects management strategy to manage development impacts on land, water, and air resources; developing a strategy for managing private and public lands; establishing an information, monitoring, and knowledge system; and including the aboriginal population in land use planning. Additional priorities include developing strategies for managing surface and subsurface activities (e.g., completing an oil and gas policy integration initiative, reviewing the process for identifying major surface concerns before public offerings of Crown mineral rights, and developing a major transportation and utility corridor (TUC) strategy).

A number of contracting approaches have been implemented in the United States for delivering projects in addition to the traditional design-bid-build (DBB) approach. Examples of public-private partnerships (PPPs) that enable greater private sector participation in delivering and financing transportation projects than conventional delivery methods include the following:(9)

PPP approaches are common in Australia and Canada. In New South Wales, Australia, the limit for traditional design-bid-build contracts is Au$100 million. For design-buildmaintain contracts, the range is Au$100 million to Au$300 million. Regardless of project delivery method, RTA usually retains the responsibility for acquiring property. Likewise, RTA's goal is to relocate utilities before construction starts. In practice, meeting this goal is not always possible. For the traditional delivery method, RTA reserves a certain amount to coordinate utility relocation activities with utilities. As needed, RTA asks utilities to request quotes or bids from potential contractors, which RTA uses to review and approve the proposed work and budget. Recently, RTA started to require contractors to have utility coordinators at the jobsite. According to RTA officials, this tactic has been very effective.

A contracting approach gaining popularity in Australia is the "alliance" contracting approach. First developed by British Petroleum (BP) in the 1990s in connection with problematic, risky oil reserves in the North Sea,(10) the alliance contracting approach requires project owners and contractors to work together as a single team, with clearly defined shared risk and reward contractual provisions. Australian states use the alliance approach in situations with significant uncertainties on the optimum solution for a project. Those uncertainties include unpredictable risks, a project that is difficult to scope or for tenderers to price, time pressures, and the state's desire for breakthroughs and innovation.

For example, on the Seacliff Bridge project in New South Wales (figure 6), a road segment between Coalcliff and Clifton was closed to traffic for more than 2 years because of geotechnical instabilities (including frequent rock falls and slippage of road sections into the sea) and intolerable risks to the public. RTA chose an alliance approach because it was difficult to define the scope and the optimum solution and because strong pressure from the community to reopen the road as soon as possible resulted in a tight delivery schedule.

Figure 6. Seacliff Bridge project in New South Wales.

Figure 7. North-South Transport Corridor in Adelaide, South Australia, with Anzac Highway underpass.

In the case of the North-South Transport Corridor in Adelaide, South Australia, DTEI faces numerous challenges to realize the vision of a free-flow corridor in a complex urban environment that includes numerous signalized intersections—some with major arterials, right-of-way acquisition, and utility relocations. Figure 7 shows the final design of the underpass at Anzac Highway. DTEI chose an alliance approach because of the complexity of the project and the requirement for a constructable solution.

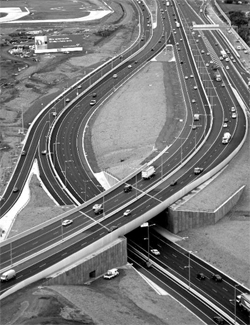

On the Tullamarine–Calder interchange project on the south side of Essendon Airport in Melbourne, Victoria, VicRoads chose an alliance approach because of the complexity of the project environment and the need for a speedy completion schedule (figure 8). In this case, the alliance was not directly responsible for land acquisition, although it played a key role in negotiating outcomes that allowed the project to proceed. Utility relocations were the responsibility of the alliance, which was also able to modify the design to mitigate utility relocation costs. Flexibility in design allowed additional shortening of one runway for a slightly larger land take, eliminating the need for retaining walls.

Figure 8. Tullamarine–Calder interchange

project in Melbourne, Victoria.

In the alliance approach, the transportation agency uses an early contractor involvement (ECI) model that focuses on assembling and integrating the best possible leadership, management, and project execution teams based on qualifications and experience. Each team includes participants from both the selected consortium and the transportation agency. For example, for the Tullamarine–Calder interchange project in Melbourne, Victoria, VicRoads used an alliance management framework that included an alliance leadership team to provide overall leadership for the project, an alliance management team in charge of day-to-day alliance management responsibilities, and a wider project team in charge of delivering the project (figure 9 below).

In the alliance approach, decisions are made on a "best-for-project" basis (as opposed to a "best-forindividual" basis) since the alliance wins or loses as a group.(10) In the case of the Tullamarine–Calder interchange project, a best-for-project approach included the selection by the alliance management team of the most suitable individuals for specific project roles (figure 9). As table 2 shows, those individuals could be from the selected consortium or the transportation agency, depending on the specific expertise area needed. In some cases, VicRoads determined that one party would be best suited for certain roles. For example, VicRoads determined that bridge design and construction would be the responsibility of the selected consortium. Conversely, it determined that right-of-way acquisition would remain the responsibility of VicRoads or a specially appointed consultant.

Click image to enlarge

Figure 9. VicRoads alliance management framework for the Tullamarine–Calder interchange project in Melbourne, Victoria.(11)

| Core Competence/Skill Area | Primary Source of Resource(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VicRoads or direct consultant | Proponent | Best for project basis | |

| Road design (grade separated) | X | ||

| Road construction | X | ||

| Traffic management during construction | X | ||

| Bridge design | X | ||

| Bridge construction | X | ||

| Drainage system design | X | ||

| Project management, controls and reporting | X | ||

| Estimating | X | ||

| Multidisciplinary design management and coordination | X | ||

| OH&S Management | X | ||

| IR | X | ||

| Environmental management during construction | X | ||

| Maintenance provision during construction | X | ||

| Land acquisition | X | ||

| Service relocation | X | ||

| Airport facility design | X | ||

| Airport facility construction | X | ||

| Traffic management/planning/modeling (design) | X | ||

| ITS | X | ||

| Noise design | X | ||

| Geotechnical investigation | X | ||

| Feature survey | X | ||

| Pavement design | X | ||

| Lighting design | X | ||

| Road safety audit | X | ||

| Environmental design/landscaping,flora,etc. | X | ||

| Legal advice re subcontracts/suballiances | X | ||

| Community relations management | X | ||

| Communications/PR | X | ||

| Community consultation | X | ||

| Legal advice re stakeholder agreements | X | ||

| Maintenance provision during defects liability period | X | ||

An early contractor involvement approach means the alliance team is involved during the project scoping and design phases. Because no bidding occurs at the end of the design phase (since the consortium was selected earlier), the alliance approach requires transparent communications between the parties, particularly on compensation and cost structures, to ensure the best possible result while minimizing the risk of cost overruns. Strategies to achieve this goal include establishing a fee structure for all direct project costs that uses open-book accounting and is viewable by all parties, a separate corporate overhead and profit calculation (e.g., as a fixed lump sum set as a percentage of the target cost), and clear gainshare-painshare arrangements.(10) Development of the target cost is one of the most important elements because that cost is used as a benchmark against which actual costs are compared at the end of the project.

Gainshare-painshare arrangements involve sharing risks as well as opportunities. For example, if a pipeline is unexpectedly found during construction, the focus is on finding a solution instead of blaming one of the parties for not identifying the pipeline earlier during the planning and design phases. In general, the alliance team is responsible for coordinating effectively with utilities early and finding optimum relocation strategies. Only one team interacts with utilities during the design and construction phases. The alliance team also presents a unified front for dealing and negotiating with property owners.

Gainshare provisions include establishing how to share any net monetary savings at the end of the project (e.g., x percent for the DOT and y percent for the commercial partner). To minimize risk, the DOT has a clearly identified list of objectives it wants to achieve during the life of the project, including good working relationships with other transportation agencies and adjacent property owners and no disruptions to traffic. Innovation is also encouraged. For example, as part of the North-South Transport Corridor in Adelaide, South Australia, the alliance team has used three-dimensional (3-D) visualization techniques and posted video clips on the Internet to explain the project to a wide audience.

At Alberta Transportation, regardless of project delivery method, right-of-way acquisition is usually the responsibility of the department because the agency's power of expropriation cannot be extended to the highway contractor easily. Without this power, assigning the contractor right-of-way acquisition responsibilities would have a large negative impact on the costs and schedule. In the case of DBFO projects (e.g., the Northwest Anthony Henday Drive project, which is part of the Edmonton Transportation/Utility Corridor(12)), if the contractor decides that additional land outside of the right-of-way is required for the project, the contractor is responsible for acquiring that additional land. After the DBFO contract expires, the contractor transfers the land to the department for a nominal purchase price of $1.

In the traditional DBB project delivery method, Alberta Transportation (via its consultant) retains responsibility for ensuring that all utility relocations are completed or at least prearranged before letting the highway construction project. For DB and DBFO projects, the contractor is responsible for the road design and therefore is responsible for coordinating utility relocations. Depending on the magnitude of the utility relocation effort, some preliminary investigation of relocation requirements may take place during the tendering phase when bidders establish contact with utility stakeholders. The department might also establish contact with utility stakeholders on behalf of the bidding teams (e.g., by holding utility stakeholder meetings or even starting some relocation work early when it is clear that the relocation work would otherwise jeopardize the project schedule if left to start at the time of project award).

In reality, Alberta Transportation is able to determine actual utility relocation costs only in the case of DBB projects. For DB and DBFO projects, utility relocation costs are typically buried in the overall bid prices. Alberta Transportation officials suspect that bidders inflate their bids with contingency allocations because it is not possible for bidders to advance their designs far enough during the bid stage, which, in turn, forces utility companies to provide conservative utility relocation cost estimates. The department accepts this additional cost as a reasonable premium to pay to transfer the utility relocation risks to the contractor.

In Ontario, MTO has relatively limited experience with alternative project delivery methods. Highway 407ETR is the only example of a finance-operate model, and only a few smaller contracts have followed the DB model. In cases in which MTO has used an alternative project delivery method, it has retained responsibility for the right-of-way acquisition process because it could not extend expropriation powers to the private partner.

In recent years, developers have built a number of transportation structures in Ontario, particularly interchanges. In this case, the developer is responsible for everything, including right-of-way acquisition, utility relocations, design, and construction. MTO provides oversight at every step to ensure the developer complies with appropriate MTO standards and specifications. At the end of the project, MTO takes ownership. As part of the agreement, MTO charges an upfront fee to cover anticipated operation and maintenance costs of the new facility. The fee is based on a life-cycle cost analysis. On occasion, developers have agreements with local municipalities in which the municipalities agree to assume responsibility for maintaining the facility. In this case, MTO considers both options, always ensuring a cost-neutral situation for the ministry.

In general, training and professional development takes place at the project level. Requirements and programs vary, but all the agencies visited place a strong emphasis on training, professional development, and continuing education.

In Australia, several universities offer formal educational programs for property valuers. A typical full-time, 3-year program offers a degree with a major in property. Coursework usually covers areas such as accounting, construction, property valuation, contract law, statistics, business finance, marketing, geographic information systems (GIS), property economics, property law, planning and environmental law, and property and asset management. Valuers have the opportunity to become members of the Australian Property Institute. In New South Wales, valuers must be registered with the Office of Fair Trading before undertaking valuation work. Other Australian states do not have similar licensing or registration requirements.

In New South Wales, the NSW Streets Opening Conference sponsored the development of a pilot training course for transportation and utility personnel involved in locating utility facilities in the field. The focus of the course was to increase awareness and provide basic information about the different types of utility infrastructure within the road reserve. The course includes several modules, one for each type of utility (e.g., water, electric, communications, and so on), and includes descriptions of commonly used utility features as well as sample pictures and corresponding drawing symbols. The material also includes tips on how to read and understand record plans. The training course will provide the foundation for a formal accreditation process for utility location services.

Through VicRoads International, VicRoads has an active presence abroad. VRI is a commercial arm of VicRoads that provides export opportunities for Victoria's practices and technology by leveraging VicRoads' technical support and knowledge base. VRI works with Australian and international business partners to export its roadrelated consultancy services. VRI has delivered project management and consultancy services in more than 25 countries across numerous project disciplines. An integral component of the VRI program is to provide staff members with the opportunity to travel and work abroad, which in the long term benefits VicRoads because it promotes personal growth and professional development. Staff members who participate in the program usually report high levels of personal satisfaction. VicRoads also promotes its presence abroad as a recruitment strategy.

In Alberta, Alberta Transportation outsources most work, including right-of-way acquisition and utility coordination. However, the agency is revisiting its 100 percent commitment to outsourcing. Alberta Transportation property agents are required to have the Accredited Appraiser Canadian Institute (AACI) designation with the Appraisal Institute of Canada (AIC) or Senior Right-of-Way Agent (SR/WA) designation with the International Right of Way Association (IRWA) and be members of either association. Department staff members attend the annual Alberta Expropriation Conference and semiannual partnering conferences with consultant land agents and engineering consultants.

Most employees at Alberta Infrastructure's Realty Services are also members of AIC or IRWA. Realty Services is a corporate member of the Alberta Expropriation Association. To promote the government as an employer of choice for right-of-way professionals, a member of the Land Process Management Committee (LPMC) (a crossdepartmental committee with members from both Alberta Transportation and Alberta Infrastructure) gives annual presentations at institutions such as Olds College (which has a 2-year program to train land agents).

In Ontario, MTO outsources much of its work, except right-of-way acquisition, although some regional offices prepare some appraisals. Similar to Alberta Transportation, MTO has begun to do more work internally to develop in-house expertise to address needs such as succession planning, the ability to provide needed services, and the management of services that continue to be outsourced. Retention and professional development opportunities at MTO include flexibility and training, usually through outside sources such as professional organizations (e.g., AIC or IRWA).

| << Previous | Contents | Next >> |