U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Main Roads—www.mainroads.qld.gov.au

Transportation Infrastructure ManagedBy Main Roads

|

Queensland is the size of Alaska (2.5 times the size of Texas), but has a population similar to that of Iowa. This could change, because Queensland expects a 50 percent population increase over the next 25 years, making it the fastest-growing state in Australia and possibly its most populous in 30 years. In concert with this population growth, freight demand is expected to double over the next 20 years. This is a particular challenge to road managers because much of this truck growth will be in the natural resource industry. Three of the top five exports are natural resource-related and the trucks serving this industry tend to be long and heavy. All of this growth places increasing pressure on Queensland's transportation network to handle significant increases in travel.

The Department of Main Roads is the agency responsible for 34,000 km (21,127 mi) of Queensland's road network, representing 20 percent of the state's total road network but carrying 80 percent of the traffic. This road network is the state's largest single physical asset, with a replacement value of A$26.6 billion (US$20.1 billion). To manage this network, Main Roads is divided into four regions and 14 districts. Routine maintenance of this network is often carried out with Road Maintenance Performance Contracts.

About one-third of the maintenance is done this way, and of this one-third, two-thirds is done by maintenance organizations or firms and one-third by local government. Although Main Roads has considered outsourcing all maintenance, the employment needs of rural Queensland have created political pressure to keep public employment. The prominent player in outsourced maintenance delivery is RoadTek, Main Roads' internal commercial business provider. With a usual contract period of 1 to 2 years, contractors become an important component of the network condition and operations management structure.

According to Main Roads' officials, the key transportation challenges Queensland faces include providing the infrastructure necessary to accommodate increasing travel growth, dealing with increasing congestion (including incorporating transit services into major road corridors), serving rural areas accessible only via roads, rehabilitating a large number of bridges subject to heavy truck loads, and meeting customer expectations in a financially constrained environment. Main Roads' officials stated that they want their agency to be viewed more as a road management agency, not just a road builder.

A 1994 law that required government agencies to adopt an outcomes-based approach to business decisions was a major impetus for Main Roads' evolution toward asset management. This was the beginning of Main Roads' concerted effort to adopt a road network strategy based on performance monitoring.

The first major steps in a government-wide approach to asset management occurred in 1997 when Queensland's Treasury Department adopted the Financial Management Standard 1997, which required agencies to undertake asset strategic planning as part of their strategic and operational planning processes.[24] Such planning was charged with focusing on an asset's life cycle, associated costs, and how the asset aligns with service delivery outcomes and government priorities. An asset strategic plan was required, which was intended to reinforce the government's policy that public investment in infrastructure should adopt a whole-of-government approach so that limited resources could be focused on obtaining the most value to the community. Queensland's public-private partnership (PPP) policy also states that when an asset has an initial capital cost exceeding A$30 million (US$22.6 million) or when the net present value (NPV) of the asset's whole-of-life costs exceeds A$50 million (US$ 37.8 million), then agencies must, in conjunction with the Asset Strategic Plan Guidelines of the Queensland Treasury, undertake an analysis using a value-for-money framework.[25]

Because the 1997 standard was so important in initiating asset management practices throughout Queensland's government, it is worthwhile to examine what was required in the asset management plan. The plan required the following:

Although Main Roads had already begun some effort in pavement and bridge management before 1997, the standard spurred the agency to make its asset management program more comprehensive. In addition, as of 2000/2001, only one-third of local governments had some form of pavement management system, so the standard spurred interest among local officials as well for more comprehensive asset management efforts.

In 2000, Queensland Treasury issued guidelines to replace the 1997 standard that have had an especially strong influence on asset valuation. The Non-Current Asset Accounting Guidelines for the Queensland Public Sector provide guidance on identifying, valuing, recording, and writing off noncurrent physical and intangible assets.[26] This new guideline requires assets to be measured either at historical cost or fair value. This has resulted in Main Roads adopting an asset management approach to asset valuation that is one of the few such applications the team observed on this scan. This asset management approach has led to, or at least occurred simultaneously with, a changing Main Roads philosophy of wishing to be viewed more as a road manager than a road builder.

“In the short term, we must deliver our capital program, but over the long term, we are responsible for the investment in our road asset. . . . It is not an either/or decision; we must do both.”

— Main Roads Official

Another driver for asset management found in Victoria, but not as prevalent in Queensland, was the legal treatment of liability. Unlike Victoria, where the law on nonfeasance[27] was overturned (resulting in the need for a defensible investment decisionmaking process), Queensland has kept its nonfeasance law. Queensland is waiting to see what happens in Victoria to determine if it is workable and desirable.

Main Roads has established a Road Asset Maintenance Steering Committee (RAMSC) to oversee the development of road and bridge maintenance policies. This group oversaw the publication of the Road Asset Maintenance Policy and Strategy, a vision for road asset management practice in the agency. In the agency itself, the primary organizational unit responsible for asset management is the Road Network Management Division, although many other units contribute data and expertise. This division is responsible for asset management information systems, which, according to the division's description, are “integral to enabling our division to play a major part in the analysis of road network and maintenance solutions.”

Important to the implementation of asset management in Main Roads are principal engineer positions that are responsible for network performance, including asset management delivery, which have been established in all regional offices. Main Roads' asset management program has also developed targeted training programs and courses aimed at improving the asset management capabilities of its own staff.

Main Roads has established a unique institutional structure for decisionmaking at the regional level. Called the Roads Alliance, this program encourages local governments to join with peers with mutual interest in the road network to identify and assign priorities to roads of regional significance.[28] Regional road groups (the term used to describe this peer committee) have been formed in all 15 regions. Main Roads participates in these road groups, which now include 125 of the 126 local councils. Local governments and Main Roads contribute investment funds to a regional pot of money to spend on roads of regional significance.

By 2005/2006, the regional road groups are expected to develop 5-year investment programs that will be incorporated into the Main Roads Improvement Program. These investment programs will include a 4-year fixed schedule of investment along with one indicative year. Other conditions are that at least 80 percent of Main Roads' funds must be allocated to the state road network, no group member is required to spend its funding outside of its jurisdictional boundaries, and all routine maintenance is the responsibility of the road owner. Preliminary experience with this structure has suggested that local governments understand the need for a regional perspective on asset management and, in some cases, have allocated their own funds to support projects outside of their jurisdictions.

Another benefit of the Roads Alliance is that it has developed joint purchasing and resource-sharing practices. These practices range from improved project-scheduling procedures to better methods of identifying risks. A Roads Alliance Road and Bridge Asset Management Kit has been developed that lays out the key steps in asset management practice. The Roads Alliance also sponsors workshops and training sessions on tools and techniques to improve the productivity of public works employees.

Main Roads relies on plans and decision support systems to support policy development and organizational decisionmaking. For example, Roads Connecting Queenslanders is the overall statement of vision and strategy for a cost-effective road investment program in Queensland.[29] This plan, referenced in all asset management documents, establishes the overall framework for Main Roads' activities in asset management.

Figure 20.Similar to other Australian states, Queensland has numerous timber bridges that present important challenges to its asset management program.

A Road Asset Maintenance Policy and Strategy (RAMPS) was published in September 1999 with the goal of fostering a whole-of-life performance approach to Main Roads' investments in maintenance.[30] It also defined maintenance performance standards, and recommended that an analysis-based planning approach be used to support decisions. Such a decision support system should exhibit the following desirable functions:

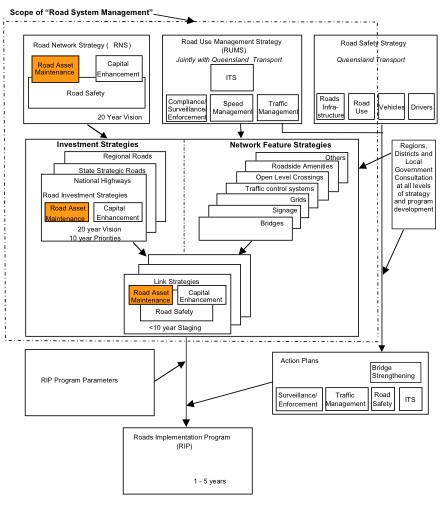

In RAMPS, Main Roads defined the relationship among the many different components of a road system management program, including the role for asset management. Figure 21 shows where road asset management and maintenance fit into this broader scheme. The concept of road system management has been recently reinforced with the development of a strategic framework for asset management that links different asset management functions to decisionmaking (based on Austroad's Integrated Asset Management Framework). This framework is called the Road System Manager, whose purpose is to provide “a consistent state-wide understanding of how Main Roads conducts its business” and a “high level view of Main Roads' end-to-end processes and key deliverables in meeting Government priorities and community outcomes, thus providing an environment for decisionmaking, policy development and support."

Note that the word “asset” is not in the term “road system manager.” Main Roads officials believed that because of confusion about what asset management might entail (maintenance? preservation? rehabilitation?) it was best to keep asset out of the term. The specific objectives of the road system manager framework are the following:

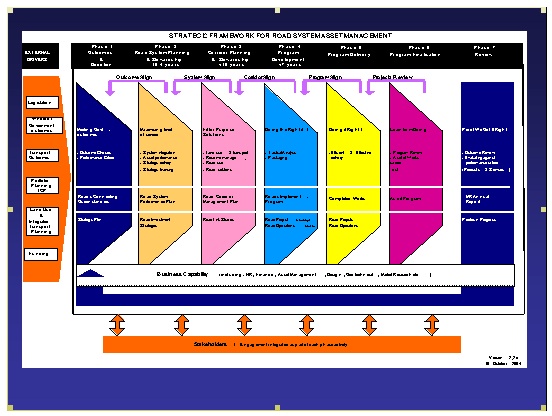

Figure 22 shows the strategic framework for road system management. As noted by Main Roads' officials, this framework also represents a subconscious change in organizational mindset. Even though changes in performance-oriented business practices in the agency had been tried, funding allocations had still been done on a traditional basis and at levels similar to those of previous years. There was thus a sense that something more than just performance-based decisionmaking was necessary. The Road System Manager framework is attempting to evolve toward a road system performance perspective, strongly tied into budgeting.

Because of its importance in explaining the linkage between asset management and decisionmaking in Main Roads, the key components of this framework will be described below. The first set of framework phases—phases 1 to 4—was called “aligned decisionmaking.” This meant the framework was intended to relate agency outputs to desired government outcomes, align prioritization of plans and programs with these desired outcomes, conduct sensitivity analyses with funding scenarios, and accommodate broad policy statements. It adopts a whole-of-government outcomes orientation and, when institutionalized, is expected to survive any change in government or administration.

Figure 21.Road asset maintenance in the context of road system management in Queensland.

Figure 22.Strategic framework for road system management in Queensland.

Phase 1: Outcomes and Direction—Sensing and interpreting the external environment to provide tangible direction to Main Roads' outcomes and outputs. This phase uses government policies, community input, market research, and Main Roads' documents that outline the desired directions for the road network as a means of making sure Main Roads is following the direction desired by the public. Main Roads' strategic plan is a primary input into this phase.

Phase 2: Road System Planning and Stewardship (15-plus years)—Translating policy directions and strategic choices/priorities into action plans. This phase includes modeling and other data-based analysis efforts to understand different aspects of road performance and to conduct investment analysis, including forecasting of future performance. The major output of this phase is a Road System Performance Plan that includes a financing plan, a priority network plan, identification of strategic asset metrics (such as condition measures), identification of 39 strategic delivery metrics (e.g., dollars per kilometer), and a network safety analysis.

Phase 3: Corridor Planning and Stewardship (less than 15 years)—Developing future-oriented plans and investment strategies for corridors, as well as stewardship of the current asset and operation conditions. The corridor plans should be multimodal and include consideration of land use and cultural heritage. The term used to describe the types of actions to be considered is “fit-for-purpose” solutions. Main Roads regional directors must present proposed corridor investment plans to the deputy director-general of Main Roads for approval and final decision.

Phase 4: Program Development (less than 7 years)—Producing priorities for projects in maintenance, operations, and network enhancement. Weighting methodologies for seven elements have been developed and approved legislatively. The major result of this effort is a 5-year Roads Implementation Program (RIP) and production of road project concepts. Main Roads referred to this phase as “Doing the Right It!”

The next three phases were labeled “co-ordination of program, project and works management.” This meant that the Main Roads budget allocation process would be tied closely to the desired outcomes defined earlier, that all aspects of transportation system performance (including land use coordination) would be included in the Main Roads strategy, and that the community would be engaged in program development.Phase 5: Program Delivery—Delivering the RIP, including the preliminary and detailed project designs, construction, and maintenance within road corridors. In essence, this phase includes all steps necessary to design, construct, operate, and maintain a road network. Main Roads referred to this phase as “Doing It Right!”

Phase 6: Program Finalization—Comparing completed projects and program delivery with baseline performance requirements. This phase compares actual performance with what was desired originally. In addition, investigations are conducted to determine what lessons can be learned from program and project experience. Main Roads referred to this phase as “Learning from Doing.”

Phase 7: Review—Measuring the actual outcomes against desired outcomes. This is the feedback loop to the decisionmaking process that informs future decisions. Main Roads referred to this phase as “Proof We Got It Right!” The band across the bottom of figure 22 represents the engagement of the community and key stakeholders throughout the decisionmaking process.

To identify a program of investments, the program is tailored to target whole-of-government outcomes, and to show increased accountability and transparency. However, Main Roads' officials stated that over time this is becoming much more complex, especially considering the many factors outside of the transportation sector that now must be considered. With uncertainties surrounding a changing federal role in funding the national road network, programming of road investments is becoming even more uncertain.

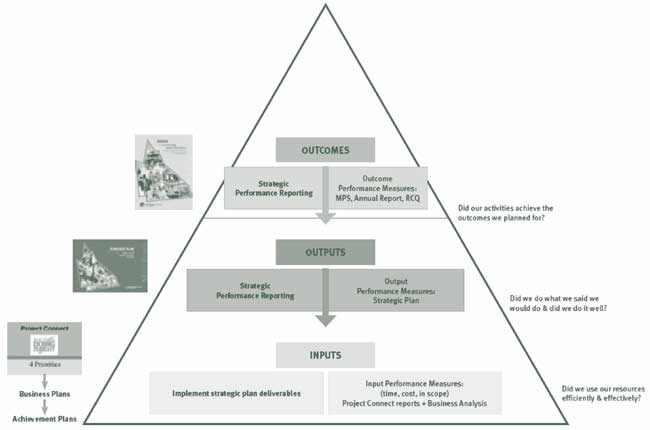

Enhancing transportation system performance and meeting the government's desired outcomes drive much of the investment decisionmaking in Main Roads. A distinction is made with the terms outcomes, outputs, and inputs, as shown in figure 23. As described earlier, Roads Connecting Queenslanders establishes the overall performance outcomes desired from the road network. Four outcome categories were identified in the report—efficient and effective transport to support industry competitiveness and growth, safer roads to support safer communities, fair access and amenity to support livable communities, and environmental management to support environmental conservation.

Main Roads' strategic plan defines the relationship between these four outcome categories and agency outputs. These outputs were defined at different levels, including road system, road corridor, road operation, road project, and business capability. Specific deliverables and schedules were specified as well. In addition, this plan explains how Main Roads will meet government and customer expectations.

Individual unit business plans specify the resources, time, and costs associated with putting in place the organizational capacity to deliver desired performance. Performance measures are defined at varying levels of specificity at each level of decisionmaking. At one time, Main Roads had a composite level of service measure for system performance, but the public and elected officials did not understand its meaning so Main Roads went back to travel time as the key measure.

Figure 23.Performance management at Main Roads in Queensland.

Although the plans identified above provide general information on how the road network's performance relates to broad performance goals, data on specific measures of interest to Main Roads' management are also collected. For example, a recent Main Roads' workshop on data and the relative importance of different data categories found that the desired data relating to network condition included, in order of preference, roughness and rutting, surface texture, field inspections, skid resistance, digital video records, pavement strength, and surface condition (e.g., cracking, patching, and edge break).

The Queensland Treasury guidance on asset management stated that “a prerequisite of sound asset management is relevant, reliable and timely information about asset resources.” According to the Treasury, this information, best provided in a structured way through asset management systems, is important for undertaking the following tasks:

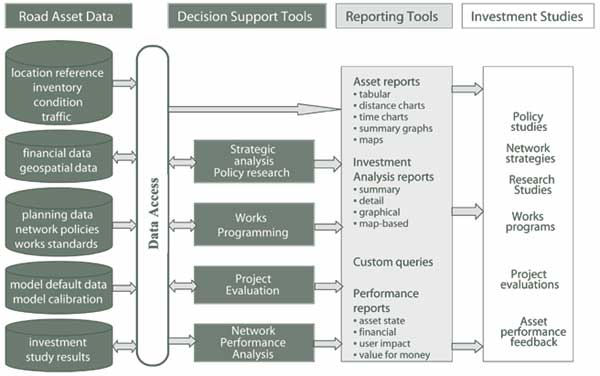

Main Roads has been developing asset management systems since the 1990s, when both pavement and bridge asset management systems were first developed. Figure 24 shows the basic configuration of the road asset management system (RAMS) used today. As shown, RAMS uses data on finance, inventory, condition, traffic volumes, and policies/standards for the decision support function it provides. A variety of reports can be generated on asset condition, network performance, and project investment.

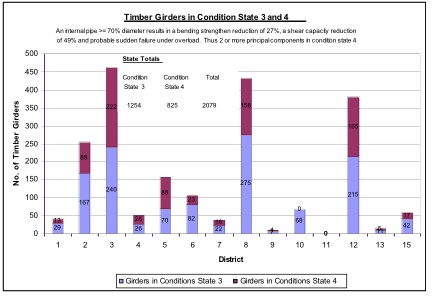

A bridge asset management system (BAMS) was first developed in the late 1990s when senior managers wanted a better sense of the condition and performance of the approximately 2,700 bridges under state control. BAMS contains Main Roads' inventory of all bridges (including 560 timber bridges) and 20,000 major culverts, and allows the user to address the risks associated with defective structures (see figure 25). The management system includes not only the inventory, but also a prioritization method for assigning priorities for bridge maintenance (discussed below), and guidelines for the types of strategies appropriate for substandard and defective bridges. As noted in the BAMS description, BAMS produces “defensible maintenance programs from non-feasance and risk perspectives.” Figure 26 illustrates the type of information BAMS can produce.

Figure 24.Road asset management system in Queensland.

Figure 25.Bridge asset management system framework in Queensland

Figure 26.Condition of timber bridges in Queensland.

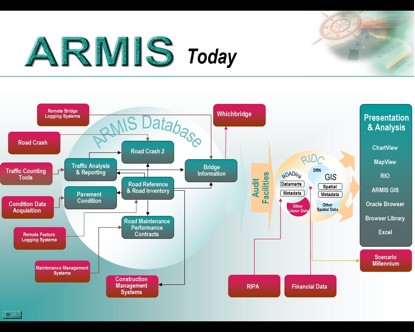

The comprehensive database available to Main Roads, called A Road Management Information System (ARMIS, see below), has several operational systems that allow Main Roads employees to manage road system data. These include a Road Reference/Road Inventory (RR/RI), Bridge Information System (BIS), Pavement Condition System (PAVCON), Traffic Analysis and Reporting System (TARS), Road Crash 2 System (RCRASH2), and a Road Maintenance Performance Contracts Management System (RMPC). For example, BIS produces the following types of asset management reports: progress against performance measures, trends in inspection, outstanding inspections, defective bridges by severity and trend, and heavy vehicle vulnerability maps. The PAVCON system provides information on such things as total district network status, relative status and priorities between road classes, detailed distribution of different types of road condition along a road section, and identification of project and maintenance priorities.

Main Roads began building a comprehensive database system in the early 1990s. This system has evolved into ARMIS. As shown in figure 27, ARMIS encompasses much of the data that a modern transportation agency needs for network management, including data on crashes, traffic volumes, pavement condition, road inventory and referencing systems, bridge condition, and road maintenance contracts. This database is linked to reporting systems such as the maintenance management system and the construction management system, allowing data to be updated when network changes occur. The data can be accessed via different media, both online as well as in print form. Those interviewed during the scan indicated that Main Roads is at a crossroads. Given that this database system has been in place about 20 years and data-collection technologies have evolved since then, the question Main Roads faces is what is the most cost-effective way of getting, storing, and accessing the data necessary to support agency decisionmaking?

Figure 27.A Road Management Information System in Queensland

To begin answering this question, officials have given thought to what types of data should be collected. For business operations at the system level, desired data include maintenance of sealed road apparent defects, sealed road pavement surface deficiencies, pavement structural deficiencies, maintenance of unsealed road apparent defects, crash investigations, network-level crash analysis, hazardous grades, and intersection upgrading records based on high crash rates/potential. For business operations at the corridor level, desired data include management of roadside and surface delineation, fatigue management, skid resistance, and traffic-generated noise in urban areas. For bridge data, Main Roads has adopted a schedule for inspections, ranging from once every year to 8 years, depending on bridge type and the results of prior inspections. For roads, 20 percent of the kilometers on which data were collected are audited, (that is, data are collected again). The district road manager must sign off on the quality of the data collected.

According to Main Roads officials, video log data are by far the most actively used by both Main Roads engineers and consultants. On an average week, this video log Web site receives about 1,000 hits.

One of the major products feeding into agency investment decisionmaking (and thus establishing an overall analysis framework) is the Road Network Investment Strategy. The purpose of this strategy is to 1) formulate a vision for the network based on industry and community demand, sound engineering principles, and realistic funding scenarios; 2) develop appropriate standards of performance and prioritize capital and maintenance dollars for each link in the network; and 3) assess benefits in terms of several criteria, including freight, efficient vehicle routing, safety, access for industry, benefit-cost ratio (BCR), community access to essential services, emergency access, environmental sustainability, and agency risk.

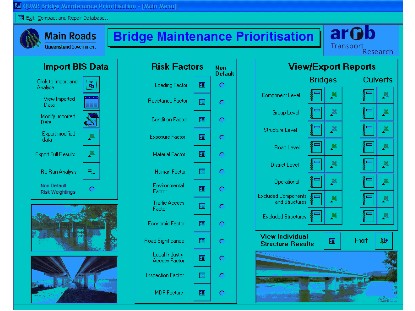

For bridge maintenance needs, Main Roads has developed a program called Whichbridge that assigns a numerical score to each bridge based on the risks attached to the condition of the bridge. The factors considered in this assessment process include condition of bridge components, effect of multiple defective components, significance of members to load-carrying capacity, global and local environmental impacts, component materials, currency of inspection data, obsolete design standards, and traffic volumes. The system, relying on Level 2 inspection reports, ranks structures based on risk exposure and safety considerations (a relative, not absolute, ranking). The probability of failure is multiplied by an assessment of the consequence of failure. The probability is expressed as a function of such things as loading, resistance, condition, inspection data, and exposure.

Consequence is a surrogate for the costs of failure, which relate to such things as human factors, environmental, traffic access, economic, road significance, and industry access consequences. Figure 28 shows the input screen for Whichbridge and the types of factors that can influence the prioritization outputs.

Table 6 shows an example of the results presented to Main Roads' management. In this table, the current risk scores are related to the best possible scores for bridges in each region. The ratio of current to best scores gives managers a sense of which region faces the most severe bridge problem (the higher the number, the worse the problem). The use of risk measures in analysis and performance monitoring has also been a very useful strategy for getting the attention of elected officials. Some Main Roads officials believe that the concept of risk is one that elected officials can grasp easily, making them willing to consider funding allocations to reduce this risk.

Figure 28.Bridge prioritization program in Queensland.

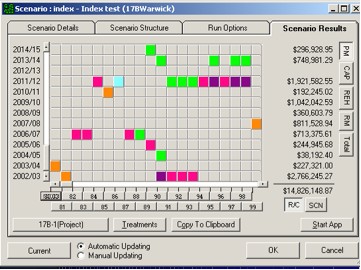

Main Roads has impressive capabilities for conducting scenario analyses. A series of software programs allows Main Roads officials to understand the consequences on network performance of different input factors such as budget levels. One of these programs, called SCENARIO Millenium, is a rule-based decision support tool that assists in maintenance treatment programming by selecting treatments based on rules and conditions, calculating costs and benefits, making optimal treatment selections for road segments, and predicting condition according to deterioration models. The program examines each road segment in a typical group and produces suggested maintenance strategies and associated costs. The user can change input assumptions relating to such things as discount rate and unit costs. Figure 29 shows a typical SCENARIO output. The colored boxes in the middle of the figure represent different treatment strategies that occur on different road segments (on the x-axis) during different years (y-axis). The users of this tool can also change the scheduled activities (colored boxes) to different time periods and assess the resulting performance consequences.

Use of this tool has already resulted in significant policy-related findings. According to Main Roads officials, the analysis has shown the following:

An interesting finding from the Queensland visit was the approach Main Roads has adopted for valuing its assets, which Treasury has approved. The original approach to this valuation, following the Financial Management Standard 1997, was fairly simple. Only four road network components were considered: bridges, surfacing, pavements, and formations. A straight-line depreciation method was used, as were standard useful lives and current replacement costs. Very small residuals (one-seventh to one-fortieth) were incorporated into the valuation. The valuation was based on road length and number of lanes, and there was very little linkage to the agency's asset management processes.

Figure 29.Illustrative results from a Main Roads SCENARIO analysis.

Given new Treasury guidelines, a reassessment of the valuation process was undertaken, resulting in 19 recommendations. The primary focus of the recommendations was to provide a stronger linkage to Main Roads' asset management processes. The most important recommendations for asset management were the following:

Main Roads adopted several of these recommendations. For formations, bridges, and surfaces, a residual value and a review of standard useful lives were introduced. Straight- line depreciation was retained for these assets because the consumption of the service potential of these assets was driven primarily by environmental factors (time) and commercial or technical obsolescence. For pavement depreciation, the rate of depreciation followed the consumption of future economic benefits (consumption of service potential), and the determination of where the asset is in its life cycle was based on the current asset management approach in Main Roads.

The effect of these changes on the discounted asset valuation was as follows:

Queensland is one of the world's leading practitioners of asset management, in particular in the application of tools and techniques. Several aspects of Main Roads' asset management program stand out.

Similar to New Zealand, the level of asset management integration with agency activities was quite impressive. The asset management plan that was developed in the late 1990s was a very important point of departure for Queensland's asset management strategy. Decisions relating to asset preservation and maintenance, linked to this and other plans, rely heavily on the performance measures laid out in Roads for Queenslanders, Main Roads' strategic plan. The level of consistency among the different levels of plans and the linkage to performance measures were found to be two critical foundations for an effective asset management program.

The evolution away from asset management toward road system management seems a logical step in the evolution of asset stewardship. The RSM framework, in which asset strategies are aligned with decisionmaking and program delivery is coordinated among different agencies and linked to a variety of goals, is a useful approach to a broader concept of network management. The linkages between the different steps in this framework, and the logical relationship between planning, programming, and coordination, result in a good model of how to consider asset needs in agency decisionmaking in the most effective way.

Main Roads clearly had the most impressive analysis capability of all the sites visited. The Whichbridge program for prioritizing bridge maintenance and the SCENARIO package for conducting scenario analysis are state of the art. In particular, the application of risk assessment in the Whichbridge program is an intriguing example of how risk can be incorporated into prioritization schemes. Both programs are excellent examples of how analysis can educate both decisionmakers and the public on the infrastructure needs facing a community.

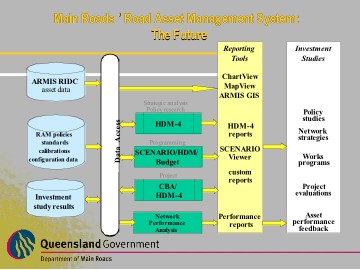

Main Roads has been developing its road network database for the past 20 years. ARMIS is recognized as having served a very useful function in Main Roads, and in itself is a valuable resource to the agency. However, questions remain about what happens next in the development of an information support base for agency decisionmaking and road system management. Given Main Roads' reputation for being at the cutting edge of information-based decision support, it will be worth watching to see what it comes up with. Figure 30 shows the latest thinking on what Main Roads' future asset management system might look like.

An interesting aspect of Queensland's asset management approach is the direction it is heading in asset valuation. Unlike other cases, where straight-line depreciation is used as part of the valuation process, Main Roads has an agreement with the Treasury to use management system outputs in determining the remaining useful lives for pavements, thus producing a more realistic assessment of asset replacement value. The assessment that Main Roads went through in examining different assumptions underlying the valuation process and determining what impact they have on net present value is an important learning experience for other transportation agencies.

Main Roads understands the human resource element of asset management as well. It provides training courses and publications on asset management aimed at increasing organizational capability in asset management practice.

Finally, the innovative, coalition-building approach seen in the Road Alliance is an excellent example of how to extend concern for asset management beyond a state's jurisdiction. Tying these activities to budget recommendations and developing an institutional structure that reinforces the mutual gain that comes from investments in asset preservation is a model to emulate for increasing the effectiveness of asset management efforts at state and local levels.

Figure 30.Future asset management system at Main Roads.

[24] Queensland Treasury, Financial Management Standard 1997, Reprint 3C, Brisbane, QL, see: http://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/LEGISLTN/CURRENT/F/FinAdminAudSt97.pdf.

[25] Queensland Treasury, Asset Strategic Management Guidelines, Brisbane, QL, July 2003, see: http://www.treasury.qld.gov.au/office/knowledge/docs/asset-planning/asset-strategic-plan-guidelines.pdf.

[26] Queensland Treasury, Non-Current Accounting Guidelines for the Queensland Public Sector, Brisbane, QL, May 2001, see, http://www.treasury.qld.gov.au/office/knowledge/docs/non-current-assets/non-current-assets.pdf.

[27] Nonfeasance can be defined as the failure of an agent (employee) to perform a task he/she has agreed to do for his/her principal (employer).

[28] For the latest progress report on the Roads Alliance, see: http://www.mainroads.qld.gov.au/mrweb/prod/Content.nsf/fbadb90201547b374a2569e700071c81/d514e8ed960961904a256bc100802eb1!OpenDocument.

[29] Main Roads, Roads Connecting Queenslanders, A Strategic, Long-term Direction for the Queensland Road System and Main Roads, Brisbane, QL, May 2002, see: http://www.mainroads.qld.gov.au/mrweb/prod/Content.nsf/fbadb90201547b374a2569e700071c81/7ceb01526342d9a84a256bc6008394e3/$FILE/MR%20RCQ%20Report1.pdf

[30] Main Roads, Asset Maintenance Policy and Strategy, Brisbane, QL, Aug. 2002, see: http://www.mainroads.qld.gov.au/mrweb/prod/Content.nsf/fbadb90201547b374a2569e700071c81/a9b38e68267717d14a256c4d00171fb7/$FILE/Part1.pdf