U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Chapters 3 and 4 of this report describe both material and workmanship and short-term (5 years or less) performance warranties in Europe. The long history of success with these short-term performance solutions has recently evolved toward longer-term guarantees of performance through the use of maintenance contracts, PPCs, and DBFO contracts. Similarly to the United States, the European hosts are dealing with growing capital project needs, as well as backlogged maintenance needs. They are also dealing with a shortage of staff and a changing role of government. All of the host countries are looking at alternative delivery methods as a mechanism to increase innovation without creating a burden on highway agency staff. While these long-term performance contracts were not the focus of the scan, all of the host countries viewed them as a natural evolution of their warranty program and spent a significant amount of time presenting them to the scan team during the visit.

The alternative delivery methods use many of the same mechanisms discussed in the short-term warranties. For example, the previous discussions of existing conditions definitions, final acceptance, performance indicators and thresholds, performance measurements, and corrective action are all very similar in the long-term performance warranties. The primary differences involve the products warranted, the lengths of warranties, procurement methods, bonding requirements or financial guarantees, design and construction contract award, payment, and responsibilities for operation and maintenance.

This chapter presents three categories of long-term performance warranties: maintenance contracts, PPCs, and DBFO contracts (see figure 5.1). The discussion focuses on those items that are significantly different from short-term warranties. All of the long-term performance contracts include both a warranty and maintenance activities. The first group only includes maintenance and is generally shorter in term (5 years). The pavement performance warranties include the maintenance necessary to warrant the project for approximately the design life of the pavement. The DBFO contracts include maintenance over the life of the project, and the term can span over multiple pavement rehabilitations.

| Material and Workmanship Warranties |

Short-Term Performance Warranties |

Maintenance Contracts |

Pavement Performance Contracts |

Design-Build- Operate-Finance |

|

|

|||

The reader should be aware that these alternative delivery methods are a relatively new mechanism in Europe. As noted in chapter 2, significant use of long-term performance warranties has only been in effect since the 1990s in the majority of host countries, and they are still widely considered to be an alternative form of contracting in these countries. There is not yet the documented success and core knowledge found with the short-term warranties. However, the European host countries are placing a lot of faith in these contracts to deliver performance by tying the contractor into the full life cycle of the product.

The majority of short-term warranties does not include routine and preventive maintenance in the contract, but rather include corrective maintenance through the performance measurement terms of the contract. Spain and the United Kingdom provided the scan team with examples of maintenance contracts that place the responsibility for routine and preventive maintenance on the contractor. In addition to maintaining pavement at a predescribed level of performance, these maintenance contracts also include items such as smaller, less serious forms of corrective action performed to prevent a distress from reaching threshold levels, signage removal and repair, snow removal, salting/sanding, mowing, and guardrail improvement or repairs.

These maintenance contracts are not necessarily tied to the original construction contract, but they are still a natural evolution of warranties as they move from short-term to long-term performance warranties. Where material and workmanship and short-term performance warranties need only examine the pavement performance after 1 to 5 years as a prediction of future performance, they do not typically warrant pavements into the preventive maintenance cycle. However, long-term performance warranties continuously examine the pavement performance well into this preventive maintenance cycle, and it follows that the contractor will perform that maintenance so that there is a clear delineation of responsibility. The contractor may also want to control the routine maintenance to ensure that drainage and other critical elements of the roadway performance are met.

Spain provided an excellent maintenance contract case study for the research team. In the 1980s the first Spanish national highways were constructed, and the maintenance of the highways was contracted externally through bids. Prior to that time the Spanish government was in charge of the maintenance. In 1987, the Spanish government awarded the first contract for the maintenance of the M30 loop around Madrid. As of September 2002, there were more than 120 contracts to manage over 3000 km of highways in the national region. Fifty-sixty companies managed these contracts, and the government still managed about 20 percent of the system. The municipalities have similar contracts for cities and urban areas.

The Spanish maintenance contracts were originally awarded on a 4-year term, but the term has recently been switched to a 2-year award with two 1-year options. The contracts are typically for 100 km of highway, but they are often shorter for rural roads. The maintenance contacts are divided into three groups:

The cost breakout for the entire network is approximately 30 percent to 40 percent for Group 1, 50 percent to 60 percent for Group 2, and 10 percent to 20 percent for Group 3. The Ministry of Transport maintains the system-wide pavement management database. Group 1 collects the data (using a subcontractor with the laboratory), but the Ministry makes the decisions when to repair the road. These data are made available to the maintenance contractor, but are maintained by the Ministry. If maintenance is required on a systemwide basis, the project is let as a large bid. If the work is less than 1 or 2 km, the maintenance contractor may do it. Typical performance indices include IRI, deflection, cracking indices, wearing, and friction.

The United Kingdom uses managing agent contracts (MAC) for term maintenance of its motorway and trunk road system. The United Kingdom started with 3-year maintenance contracts for a limited scope of work. Currently, the term is 5+1+1 (5 years as a base plus two 1-year options) if the provider, the contractor, is achieving the performance indicators successfully. The scope of work has also expanded from the initial concept. Emphasis is being placed on integrated supply chain management. The selection process includes evaluation of the plan to provide goods/services, also risk allocation within the contractor team. Maintenance includes routine matters and limited reconstruction work—if reconstruction costs are above a specified level, the job is separately procured.

As previously stated, these maintenance contracts are somewhat outside the scope of this warranty scan, but they are a natural evolution of warranties as they move from short-term performance to long-term performance. As contractors move into the longer-term pavement performance warranties described in the next two sections, they may need to acquire these maintenance competencies in order to deliver the scope of services being required by the government.

U.S. Parallel: Asset Management ContractsThe Virginia DOT embarked on a 51/2 year, fixed-price maintenance agreement for more than 1,000 lane miles on I-77, I-81, I-95, and I-381. The work includes all required restorative work, such as roadway resurfacing and bridge deck replacement (Garza and Voster, 2000). |

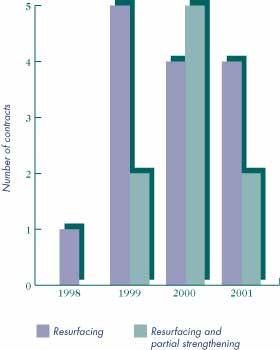

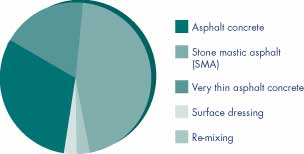

Various forms of PPCs were observed in all countries on the tour. Denmark had awarded close to 20 contracts at the time of this scan. Sweden was using PPCs for about 10 percent of its pavements at the time of this scan and is hoping to double the number by 2007. The exact number of Danish PPCs and the type of surfacing is shown in figures 5.2 and 5.3. Germany refers to these contracts as “functional contracts,” and they had awarded only two at the time of the scan. The United Kingdom uses a form of PPC though its “framework contract.” The term PPC will be used to describe all of these contracts for clarity in this report.

Figure 5.2: Danish pavement performance contracts (number of contracts)

Figure 5.3: Danish pavement performance contracts (type of surfacing).

PPCs extend performance warranties to include a warranty period that is closer to the design life of the pavement. In a PPC, the contractor is responsible for designing, constructing, and maintaining the performance of the pavement to prespecified levels. The advantages to the owner are readily apparent. Table 5.1 offers a comparison of the lengths of warranties on standard Danish contracts and PPCs. As displayed, the owner is assured of performance over a period of 11 to 16 years in the PPCs, rather than just 1 to 5 years as seen in traditional contracts. Additionally, impenetrability of surface water and load-bearing capacity are warranted in the PPCs, but not in the standard contracts.

| Performance Indicator | Standard Contracts | Performance Contracts |

|---|---|---|

| Friction | 5 years | Throughout contract |

| Surface regularity | 1 year | Throughout contract |

| Profile and drainage of surface water | 1 year | Throughout contract |

| Rutting | 5 years | Throughout contract |

| Instability | 5 years | Throughout contract |

| Durability (raveling, joints, cracking, potholes) | 5 years | Throughout contract |

| Impermeability of surface layers | None | Throughout contract |

| Load-bearing capacity | None | Throughout contract |

| Road marking (friction, reflection, color) | 3 years | Throughout contract |

In Spain, Germany, and the United Kingdom, the highway agencies are promoting the contracts. However, the industry is the catalyst for PPCs in Denmark and Sweden. In all of the countries, the PPC forms are developing with close government and industry collaboration.

Depending on how the contractor proposes to build the pavement, the maintenance can include a number of items from filling of isolated potholes and minor pavement remarking to a complete mill and overlay of a significant section of pavement. The highway agencies are simply looking to the industry to provide a pavement that performs to prespecified standards. The PPCs allow for much more innovation from the industry. However, there is a substantial risk that the industry must be willing to take. The contractors must have design, construction, and maintenance competencies to compete for a PPC.

The advantages of PPC include that the contract is directly related to pavement performance; there is greater involvement of the contractors and contractor innovation in the process; agency demands on design oversight, supervision, and quality control are minimized; and there is an improved control of contract economy and reduced risk of exceeding the budget for the owner. Likewise, the contractor can plan its work in a long-term fashion rather than a reactive fashion upon successful award of short-term contracts. The disadvantages stem from dedicating money for a potential large network to one contractor for a long period, increased liability for the contractors, and changing environmental, political, and societal issues that are difficult to tie into long-term contracts. Unfortunately, these advantages and disadvantages are speculative given that PPCs are relatively untested by the industry.

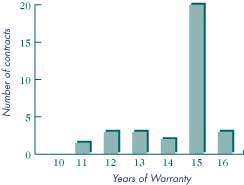

The lengths of PPCs varied. The length of the contract is loosely tied to design life of the pavement, but type of pavement, existing road conditions, and financing approach all play a role in the length of PPCs. Table 5.2 summarizes the various lengths of PPCS in host countries where the information was available, and figure 5.4 provides the lengths for Denmark's initial PPCs.

| Germany | Denmark | Sweden | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of contracts through 2002 |

2 | 17 | 23 |

| Length of contracts (years) |

20 | 11-16 | 5-12 |

|

* Germany stated that it would increase the length of the contracts to 25 years in its next set of pilot projects. |

|||

Figure 5.4: Danish pavement performance contracts (warranty periods)

In Germany's first PPC, the Federal Ministry of Transport allowed for alternate bids between concrete and asphalt. It chose a period of 20 years and based the award on a life cycle cost evaluation. Concrete was selected as the most economical material for a period of 20 years. Our hosts stated that the next set of contracts would be let with a period of 25 years and that they expected that asphalt would be the more economical choice given the expense to repair concrete joints after a 20-year period.

Denmark and Sweden have begun to more aggressively employ PPCs. In Denmark, the municipalities are the sole users of the contracts and they are choosing 11- to 16-year contract lengths. Their motivation for these lengths seems to be tied to the cash flow and financing aspects of the contracts, which is explained in more detail in the following pages of this report. Swedish PPCs currently vary in length between 5 and 12 years. The main motivation for the use of these contracts in Sweden is the outsourcing of administration to the private sector. The length is tied to the current risk appetite of the industry, and the future may see longer contracts.

The length of contract will also have a large bearing on the procurement, bonding requirements, and financing/payments of the PPC. These issues are discussed in detail in the following sections.

The best-value process, as described in chapter 3, is the procurement method of choice for PPCs. A key aspect of the best-value procedure is the application of engineering economy to the procurement—particularly equivalent annual value (please refer to figure 3.2). PPCs extend the best-value example presented in figure 3.2 because the contracts can involve a number of planned construction and maintenance cycles throughout the life of the project. The Danish Road Directorate provided the scan team with an example plan of activities and payments, which is shown in table 5.3.2

| Year | Plan of Payments Total Price (DKK)* | Plan of Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 100,000 | Pavement repair |

| 2002 | 200,000 | Pavement repair |

| 2003 | 3,650,000 | Milling, strengthening, temp. road marking |

| 2004 | 2,000,000 | Wearing course, road marking |

| 2005 | 8,000 | Maintenance |

| 2006 | 8,000 | Maintenance |

| 2007 | 8,000 | Maintenance |

| 2008 | 8,000 | Maintenance |

| 2009 | 250,000 | Road marking |

| 2010 | 8,000 | Maintenance |

| 2011 | 8,000 | Maintenance |

| 2012 | 8,000 | Maintenance |

| 2013 | 8,000 | Maintenance |

| 2014 | 500,000 | Pavement repair |

| 2015 | 50,000 | Pavement repair |

| 2016 | 300,000 | Pavement repair |

| TOTAL | 7,114,000 | Pavement repair |

| Total present value: 5,876,443 DKK | ||

| Average yearly cost: 566,150 DKK | ||

|

*All in 2001 prices. The average yearly cost is used to compare individual bids. The average yearly costs are calculated by multiplying the total present value with the factor “K”. K = r*(1+r)n / ((1+r)n - 1) |

||

2 Simonsen, P., and Thau, M. (2002). "Pavement Performance Contracts: The Alternative Contractual Relationship," Roads, PIARC, World Road Association, No. 315, pp. 45-56. This example was subsequently published in the journal Roads. Examples from this article are used for reference throughout the remainder of this section.

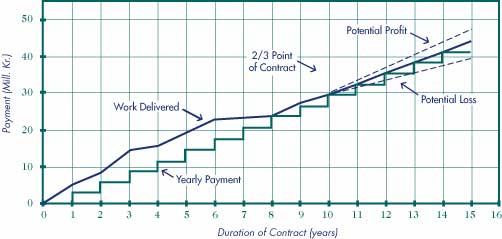

Different contractors may have alternative construction activity strategies. For example, one contractor may choose to conduct major construction in the first year to minimize the maintenance costs throughout the life of the project, while a second contractor may choose to keep the existing pavement performing at acceptable levels through minimal repairs and defer the major construction until later in the contract. As seen in figure 5.5, the contractor chose to delay milling and strengthening until year three of the contract. This will delay its major investment, but it will need to conduct any necessary pavement repair in years one and two to maintain the pavement at the level of performance specified in the contract. The average annual value for each of the strategies can be determined and used in the best-value procurement described in figure 3.2.

U.S. Parallel: Pavement Performance ContractsThe following is a quote from "Performance-Based Contracting for the Highway Construction Industry" by Carpenter, Fekpe, and Gopalakrishna, 2003.

|

While this procurement process has been successful on a number of projects in the host countries, the scan team noted that it could be quite sensitive to both the period of analysis and the discount rate specified by the owner. The formulas used to calculate average annual value are, after all, just a model of the actual costs that will be realized throughout the life of the project. As the length of this analysis increases, the models are potentially less accurate. The owners must also take care in choosing appropriate discount rates, which is not a simple task. Inappropriate analysis periods or discount rates yield inaccurate results.

Bonding on PPCs is even more critical than bonding on standard warranty projects because the contractors assume a larger investment over a much longer period of time. PPCs create a burden on both the contractor and the surety industry. Ideally, a large performance bond (5 percent or more) could be written for the life of the contract. In 1999, Denmark experimented with several different models for setting up performance bonds. One of these comprised a 5 percent bond based on the total contract sum for the life of the contract. In addition, a minimum of 15 percent of the total contract sum should not be paid before two-thirds of the duration of the contract. Another model called for a bond of 10 percent throughout the contract. But as Denmark later discovered, bonds of this size and duration are not maintainable within the policies of the surety firms. Since 2000, Denmark has settled on a 5 percent bond for 5 years and is working on other innovative payment mechanisms to ensure the solvency of the contractors.

Payment mechanisms for PPCs have the potential to be attractive for both the owner and the contractor. Multiple payment models were shown to the scan team, but they all involved much more standard payment sums than that found in traditional planning and bidding. The government or municipality has the option to offer an equal annual sum payment for the contract, which allows it to plan its budget. The contractor can expect an even cash flow, which allows it to plan its work and equipment investment. However, the contractor may need to finance some of the construction costs, as work will be completed before the payment is received from the government. PPCs often require the contractor to partner with a financial institute. The financial institutes are likely to see this type of contract as a good risk because the government is the source of revenue for the contractor. The graph in figure 5.5 is based on the payment mechanism for a PPC in Ronnede, Denmark.

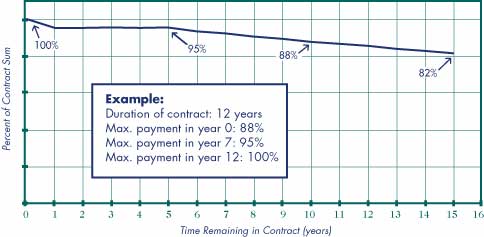

Figure 5.5: Payment model example.

Figure 5.5 is only one model for payment, and it can create a large financial burden for the contractor. Other models do not pay on a stipulated annual basis, but rather pay as a percentage of work completed for the first two-thirds of the contract. The contractor is only paid for work accomplished, until two-thirds of the warranty period has passed, whereupon it is paid according to the schedule whether work is required or not. This will allow the contractor to make a profit in the same manner as described in figure 5.5, but it will not create such a significant financial burden. However, the government is at greater risk of having the contractor default in the last 5 years of the contract. The Danish Draft Pavement Performance Specification recommends a payment schedule with significant retainage for completed work to protect against such a default. Figure 5.6 displays the recommended retainage schedule from the Draft Specification.

Figure 5.6: Maximum accumulated payment as percentage of contract sum.

Given the payment schedule in figure 5.6, the contractor will not be paid for 100 percent of the work until the final year of the contract. For example, if the work is completed in year 1 of a 16-year PPC, the government will pay only 88 percent of the construction cost. This retainage is lower as the contract moves forward. In years 10 to 15 of the contract, this retainage remains constant at 5 percent, and full payment is made in the final year. This payment system obviously protects the government in case of contractor default, and although the retainage creates a financial burden for the contractor, the long-term assurance of work allows for better planning of resources and equipment. The contractor also has the same incentive to keep the pavement at peak performance in the last years because it is paid the stipulated annual sum regardless of whether it is performing work or not.

Additional payment incentives and penalties are applicable to this system. In cases of noncompliance with the stated pavement specifications, PPCs often include a penalty system. These penalties may include no payment until the performance conditions are met or a monetary penalty in addition to not receiving the payment. Bonuses may include a monetary incentive or a contract extension. The hosts all mentioned penalty clauses, but none discussed the specific application of bonuses.

The performance indicators, thresholds, and measurements in PPCs are similar to those found in short-term performance warranties as discussed in chapter 4. The main difference is the frequency of inspection for these items. Table 5.4 provides an example of the method of measurement and evaluation of compliance with the pavement specification. If the pavement specifications are not fulfilled, the pavement distress will be subject to remedial action. PPCs used in Denmark specify a selection of remedial methods that can be accepted (Simonsen and Thau, 2002).

As seen in table 5.4, the performance indicators are quite comprehensive. They require a comprehensive pavement management system to measure, verify, and store the data. These data are critical because they will correlate to the conditions of the roads for the users and also the contractor's profits or losses. Note that a combination of visual and equipment-based measurements are conducted. These are described in more detail in chapter 4. Note also that the time of year for the measurements is given. Many performance attributes vary in the course of time, e.g., seasonal variations affect smoothness. It is important that specifications are clear on when and where measurements are to be made.

| Performance indicator | Method of measurement | Period of Measurement | Frequency | Responsibility (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friction | ROAR | Fall | (2) | Agency |

| Longitudinal evenness | Laser | Fall | (3) | Agency |

| Transversal profile and drainage of surface water | Visual inspection | Acute | Agency | |

| Rutting | Laser | Fall | (3) | Agency |

| Instability | Visual inspection | Fall | Annual | Contractor |

| Durability | ||||

| Raveling | Visual inspection | Fall | Annual | Contractor |

| Joints | Visual inspection | Fall | Annual | Contractor |

| Deterioration: | ||||

| Longitudinal cracks | Visual inspection | Fall | Annual | Contractor |

| Transversal cracks | Visual inspection | Fall | Annual | Contractor |

| Alligator cracking | Visual inspection | Fall | Annual | Contractor |

| Potholes | Visual inspection | Fall | Annual | Contractor |

| Light reflection | Beta value | During construction | During construction | Contractor |

| Noise emission | Method not decided | |||

| Road marking: | ||||

| Reflection | Reflectometer | 1/5 - 15/10 | Annual | Contractor |

| Friction | Pendulum | Fall | By request | Agency |

| (1) Responsible for the execution of the measurements. The Employer reserves the right to supplementary measurements. (2) First and fifth year, then every 5 years. (3) First and second year, then every 2 years. |

||||

Data collection for the performance indicators shown in table 5.4 is the first part of the PMS. Once the data are collected they must be analyzed for decisions to be made. The following example was provided to the scan team for the PMS in Ronnede, Denmark. The PMS data are collected by means similar to those described in table 5.4. The data are then cataloged in a computer program such as the one shown in figure 5.7.

|

Road Id. 515-9408-0 |

From st. 0,000 |

To st. 0,155 |

Name Virkelystvej |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precent Conditions Index 3, 5 | ||||

| No. Observation | Severity | Category | % | Abs. |

| 1 Alligator cracks | 3 Large > ½ m2 | A | 7 | 56 m2 |

| 2 Longitudinal cracks 0-1 m from edge | 1 Width < ½ cm | C | 70 | 217 m |

| 3 Longitudinal cracks > 1 m from edge and tr | 1 Width < ½ cm | C | 70 | 217 m |

| 4 Ravelling | 2 Fine particles dislodged | B | 35 | 282 m2 |

| 5 Spalls or potholes | 2 Medium < ½ m2 | A | 7 | 56 m2 |

| 6 Depriessions Settlemants | 1 0-2 cm | B | 35 | 282 m2 |

| 10 Patshes | 1 Sporadically | A | 7 | 56 m2 |

| 18 Kerb | 3 < 7 cm elevation | B | 35 | 108 m |

| 19 Crossfall | 2 Along gutter | C | 70 | 217 m |

| 21 Footway | 2 Reasonable | B | 5 | 189 m |

The data from PMS are then aggregated into a “condition index.” The condition index is an aggregate of the measurements shown in the severity column above. The thresholds for the condition index are set at the beginning of the contract and correlate to the maintenance levels of each street segment, as follows: type 1 is a traffic road with bus routes, prime network streets; type 2 is a local road with bus routes; type 3 is a local road without bus routes; and type 4 is all other streets. A condition index is generated for the network as shown in table 5.5.

| Maintenance Level | Mean Condition Index | Maximum Condition Index | Maximum Percentage of Patches |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5 | 3 | 20 |

| 2 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 40 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 60 |

A survey is done on one-third of the network each year. The mean condition index must not be exceeded or corrective action will be required. The percentage of patches can be used for aesthetics. As the conditions change, the contractor may change its work plans, but the overall performance measure will remain.

Although PPCs represent only a small portion of the road network in Europe, their use is expected to rise. The contracting industry is helping to initiate this change with the goal of being allowed to introduce innovations in contracting methods and materials. The municipalities are more willing to allow innovation because the contractor is at risk for these innovations throughout the life cycle of the product. The owners are also lacking expertise to evaluate these innovations, and PPCs offer a mechanism for quicker improvement to network condition. The owners think that they are benefiting through better prices and better quality because the contractors have an incentive to provide quality products early in the process to gain profit in the end. Owners see a benefit to the public through higher-quality roadways for the duration of the warranty period (15 years).

The PPCs have mainly seen innovation to date in processes rather than products. Work is often done in April through November in a number of European countries. By planning their work ahead, contractors can get early starts and attract better workers. They can also have a better workflow or leveling for their staff. This level workflow also allows for time to do research and innovate. Finally, there is a “value chain effect” through better supplier relations that is created by the consistent workflow.

Where PPCs have extended the warranty concept to approximately the equivalent of one design life cycle, DBFO contracts are extending the concept through multiple pavement maintenance cycles. DBFO contracts are used for both construction and maintenance of European motorways. Drivers for the use of DBFO contracts range from lack of public funding to a belief that private financing and maintenance delivers a higher quality product and provides benchmarks for public sector performance.

The United Kingdom and Spain provided the team with examples of DBFO contracts. DBFO periods vary, but were commonly found to be 30 years. Both public agencies and DBFO companies commonly obtain long-term warranties from their contractors, but the team observed the use of maintenance contracts in lieu of warranties. The German, Danish, and Swedish hosts noted limited use of toll projects, but they did not share specific examples from these projects, and it was not clear if these were true DBFO projects. However, other examples of DBFO contracts throughout Europe found on other scanning tours will be discussed in this section.

DBFO contracts, commonly referred to as concession contracts, can take many forms, and the definition of a concession contract can vary slightly from agency to agency. The French have perhaps the longest history of concessions in Europe. A definition of a concession contract is found in A Draft Typology of Public-Private Partnerships as written by Rémy Prud'homme for the French Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Housing (Perrot and Chatelus, 2000):

“The concessionaire carries out all of the capital investment, operates the resulting service and is remunerated through service fees paid by users. The facilities are to be handed over to the oversight public authority at the end of the contract period.” From this definition, it can be seen that DBFO contracts are an extension of warranties, maintenance contracts, and PPCs as discussed previously in this report. However, the primary difference lies in the private sector financing mechanism and the length of the contract, which is often double that of a PPC.

The United Kingdom began its DBFO program in the late 1990s as an outcome of its Private Finance Initiative. The motivation for the contracting method has many similarities to the motivation for the use of warranties. The objectives of this program are explained in the report “DBFO - Value in Roads: A Case Study of the First Eight DBFO Road Contracts and Their Development” (British Highways Agency 1997) as follows:

To ensure that the project is designed, maintained and operated safely and satisfactorily so as to minimize any adverse impact on the environment and maximize benefit to road users;

To transfer the appropriate level of risk to the private sector;

To promote innovation, not only in technical and operational matters, but also in financial and commercial arrangements;

To foster the development of a private sector road-operating industry in the UK; and

To minimize the financial contribution required from the public sector.

The final performance results will not be known until the end of the contract. However, some selected lessons learned on the first eight DBFO projects completed in the United Kingdom are listed in the report as follows:

DBFO contracts have accelerated the introduction of cost efficiencies, innovative techniques and whole-life cost analysis into the design and construction of road schemes and the operation of roads (although the Agency had started to review these possibilities in the context of traditional methods of procurement).

The full potential of efficiencies, innovation and whole-life cost analysis inherent in the Private Finance Initiative is likely to be fully unlocked only when the private sector is involved in the outline design of the road scheme, which they are then obliged to construct, operate and maintain under a DBFO contract. This requires the private sector to assume some planning risk. Some of the DBFO projects announced introduce the concept of planning risk and will test the proposition that this will deliver better value for money.

The risk allocation on DBFO contracts has been encouraging. Two areas where transfer of risk to the private sector has delivered good value for money are protestor action and latent defect risk. The Agency will continue to look for risk transfer to ensure that the DBFO contracts remain off- balance sheet.

DBFO contracts have delivered value for money. Cost savings (compared with the public sector comparator) have ranged from marginal to substantial; for Tranche I and 1A DBFO contracts, the average cost saving is 15%.

With eight contracts let and expressions of interest received for further projects, it is clear that a road-operating industry is developing. The same consortia (with a few changes in composition) have appeared as bidders on projects within each group.

Durations of concessions in Europe can be found from less than 5 years to more than 75 years, but the majority are under contract for 15 to 30 years. Many of the contracts also contain windows of profitability for determining the end of the contract given that traffic forecasts for 30 years in the future are questionable. If traffic forecasts are wrong, there are only two options for equitable compensation for the project: change the rate of tolls (or payments) or change the duration of the contract. Political and financial viability typically limit changes in the rates charged. Possible solutions to problems caused by inaccurate traffic forecasts are to provide some mechanism for changing toll rates and, if necessary, changing the total duration of a concession to provide an equitable compensation to the concessionaire.

The hosts discussed a number of financing and payment options for funding DBFO projects. The United States typically employs a user-based toll paid directly by the user. Both the United Kingdom and Spain described the use of “shadow tolls” for their DBFO projects. Shadow tolls are an alternative financing payment mechanism in which the government pays a private sector partner (DBFO or concessionaire) for a project on the basis of the number of vehicles that use the facility. Traditional sampling methods and high-tech real count mechanisms are in use to count the vehicles for the shadow toll payments. The government receives the initial project financing from the private sector partner, and the partner takes the risk/reward for the number of vehicles that use the road. In addition, the operational nature/characteristics of the shadow toll payments may assist the government in more effectively managing its debt. This is because shadow toll payments are determined and made on a periodic basis—most commonly on an annual basis. Accordingly, the government and investment community may properly consider these shadow toll payments to be an item of operating expense; and, as an operating rather than capital expense, it generally need not be included in calculating debt ratios or debt capacity. Such an operating definition thereby provides the government with debt- management flexibility in the event that its revenues fall below expectations or if its cash-flow position deteriorates for some other reason.

As previously described, the role of a concessionaire goes far beyond simply warranting a project. Not only do the concessionaires have to maintain prescribed quality for the government, but also they now must prove to their financial lenders and shareholders that they are delivering and maintaining a quality product. From what the host concessionaires described on the scan tour, these lenders and shareholders are sometimes more demanding than the highway agencies have ever been.

Unfortunately, the European hosts on this Asphalt Pavement Warranty Scan did not provide the performance terms of the DBFO contracts. However, the performance terms of a similar DBFO project were provided from Portugal for the 2002 Contract Administration Scanning Tour (FHWA, 2002). The performance terms of that contract include:

The Concessionaire must keep Motorways in very good conservation and perfect condition of utilization, carrying out all the necessary works in order to permanently satisfy the Motorways purposes.

The Concessionaire is responsible for the high standards of conservation and functioning of environmental monitoring equipment, environmental conservation and preservation systems and noise protection system.

The Concessionaire must respect minimum quality standards, such as pavement bond and smoothness, conservation of signaling, clients assistance and safety equipment.

They have four separate performance contracts:

- Contract 1

- Contract 2

- Contract 3

- Contract 4

As demonstrated above, the performance terms of the DBFO contract are based on many of the same performance measurements being used for warranty contracts. Because the overall goals of ensuring performance for the traveling public are similar, the DBFO contracts can be viewed as an extension of warranty contracts. However, DBFO contracts transfer much more of the risk for financing and performance to the private sector. DBFO contracts constitute a major departure from traditional highway delivery in the United States, but if the evolution of performance contracting in the United States follows that of Europe, there may be more DBFO contracts on the not-so-distant horizon.

U.S. Parallel: Public-Private PartnershipsU.S. PPPs most closely resemble the European DBFO models described in this chapter. The following is an excerpt from the American Association of Transportation Official's Primer on Contracting for the Twenty-First Century: A Report of the Contract Administration Task Force of the AASHTO Subcommittee on Construction, which describes the use of PPPs in the United States. (AASHTO, 2001).

|

This chapter provided an overview of the evolution of short-term material and workmanship warranties to performance warranties, maintenance contracts, PPCs, and DBFO contracts. The long history of success with these short-term performance solutions has provided incentives for the European hosts to experiment with these alternative delivery methods. All of the host countries are looking at alternative delivery methods as a mechanism to increase innovation without creating a burden on highway agency staff. The contracts described in this chapter are new and somewhat untested when compared with the warranty methods described in previous chapters, but the hosts were confident that these approaches could be applied in a balanced contracting program to deliver value to the public.

The alternative delivery methods use many of the same mechanisms discussed in the description of short-term warranties found in chapters 3 and 4. Performance indicators, thresholds, and measurement are perhaps the most similar in nature. The primary differences involve the lengths of warranties, financing, and responsibilities for operation and maintenance.

The United States may well benefit from the alternative delivery methods described in this chapter. PPCs in particular may hold great benefit for counties and municipalities throughout the United States, and could gain acceptance relatively quickly. The continued application of pavement warranties will help the United States gain an understanding of performance contracting, which is critical for successful application of these alternative delivery methods. It is difficult to say if the United States will follow the same path as the Europeans in the application of alternative delivery methods, but a similar evolution may be forthcoming.

| << Previous | Contents | Next >> |