U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Figure 13. Winter maintenance on porous asphalt in Europe.

Denmark cleans TLPA pavements with a high-pressure water blast (100 bar/125 pounds per square inch (psi) followed by a vacuum to remove the fluid and solids (figure 13). Vendors using specialized equipment conduct the work. The first cleaning is conducted 3 months after construction, and cleaning is done semiannually thereafter. The water is filtered and recycled for future cleaning operations. The solids contain heavy metals, so they must be disposed of in an approved facility. To date, the benefits of cleaning have not been clearly established and the Danish Road Institute (DRI) plans to conduct future research in this area.

The Danes indicate that PA pavements begin to clog within the first year, although high-speed pavements fare better because of the cleaning action of high-speed vehicles. The Danes also indicated that if a pavement is not cleaned on a regular basis, it could become too clogged to be cleaned effectively after 2 years or less. When a pavement’s permeability becomes less than 75 seconds/10 cm, the pavement is considered too dirty to be cleaned (initial permeability is less than 10 seconds/10 cm). The test sections indicate that by the fourth year the permeability of low-speed PA pavement is significantly reduced and the noise-reduction benefits are reduced.

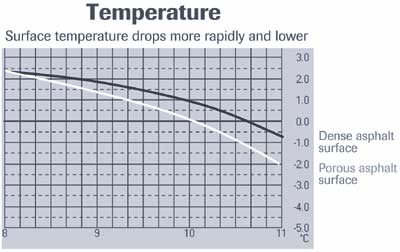

In Denmark, porous pavements require additional maintenance during the winter because of the potential for icing conditions. This is due in part to the additional surface area, which allows the surface temperature to drop 1 to 2 degrees C faster than DGA (see figure 14).

Figure 14.Comparison of surface temperatures in dense-versus-porous asphalt surfaces.

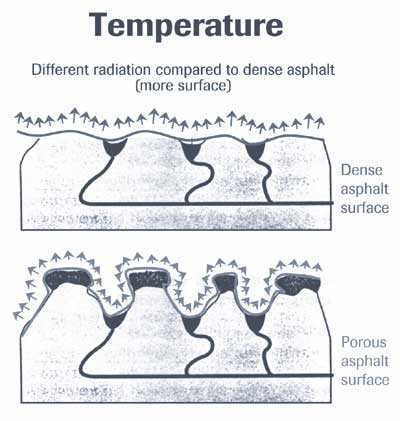

For snow and ice control, DRI does not use friction media (sand), but instead uses a wetted salt solution (water applied at the back of the truck). DRI indicated that the formation of black ice is also an issue. However, prewetted salts seem to work well and have the added benefit of leaving the top dry but with a white coating, which results in drivers slowing down. Calcium chloride and wetted salt are used to increase the even distribution of the salt and to prevent the formation of ice hats. Ice hats form because the salt tends to wash from the top of the open-graded surfaces into the pore spaces, leaving the surface susceptible to icing (see figure 15). DRI is also looking at larger salt grains to perhaps minimize this problem. DRI indicated that the porous surfaces increase salt consumption by 50 percent and result in increased callouts for maintenance.

Figure 15. Comparison of radiation from dense-versus-porous asphalt surfaces.

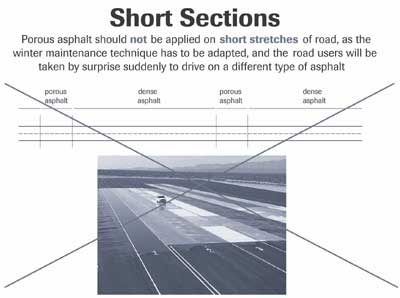

The Danes also expressed concerns about transitions from dense to porous surfaces because they may “spook” drivers in winter conditions, and indicated that short sections of porous surfaces should be avoided. DRI recommended not using porous surfaces in intersections because of the winter risks (see figure 16).

Figure 16. Short sections of porous surface.

In the Netherlands, safety is a top priority and skid resistance is required for all new surfacings. On porous pavements, the Dutch occasionally have experienced poor skid based on the slipped wheel skid test. They do not know why this happens, and they are considering requiring that a 5-year warranty be included to encourage the use of better aggregates and construction methods. When low friction is detected, speed reductions or post treatments are required. However, these treatments may negatively affect the acoustic properties of the porous pavement.

The Dutch also expressed concerns about acoustic durability resulting from clogging. Porous pavements are cleaned regularly using high-pressure water blasting (100 bar/125 psi) and then vacuumed. This is done twice yearly, but it is highly dependent on traffic, speed, and other factors. If the surface becomes completely clogged, it is impossible to clean. Following cleaning, the noise reduction and permeability are worse (because material is brought up to the surface), but these properties improve shortly thereafter. The Dutch indicate that clogging begins to manifest after 6 months. However, their experience shows that clogging does not affect noise reduction as much as first thought, perhaps 1 to 2 dB. The effectiveness of pavement cleaning is still being investigated and debated.

The Dutch no longer use PA pavements in urban areas because of clogging. In rural, high-speed applications, traffic reduces clogging, so they may high-pressure wash and vacuum only the emergency lane (shoulder).

In the Netherlands, porous pavements require additional maintenance during winter weather. About 50 percent more salt applications are required. The formation of black ice, especially on the eastern side of the country, is a challenge. The best solution is the use of prewetted salt applied as soon as the pavement begins to freeze. To address winter maintenance concerns, the Dutch use communication (signage, news, weather reports), lane closures (direct two lanes onto a single lane to assist in ice break-up), and preventive actions such as presalting before storms.

Raveling is the predominant failure mechanism, and when raveling exceeds 25 percent, the surface is replaced. The use of fog seals has not been evaluated to retard raveling.

Age hardening of the binder occurs within 6 to 8 years, but cracking or rutting is not a problem.

Test EAC sections on N279 built in 2002 are performing well. Beyond the initial roughness of the roadway, there have been no maintenance concerns.

In France, porous pavements are obtaining a service life of greater than 10 years. The French indicated that clogging is more of a problem in porous pavement than in very thin asphalt concrete. The French do not try to clean clogged porous pavements because they have not found cleaning to be effective. Instead, the mix design is optimized to eliminate or reduce clogging. When it is necessary to rehabilitate the pavement surface, milling is employed. If the worn surface is completely plugged, it is permissible to overlay the existing pavement. Porous pavement is no longer used in built-up areas because of fast clogging.

Although porous mixes can be used on any type of pavement, France has experienced some problems with the mixes freezing during the winter. As a rule of thumb, porous mixes are not used in France east of Paris’ meridian and at altitudes above 600 m. Thin mixes are typically used east of Paris’ meridian and porous mixes are used west of the meridian. Porous pavements and, to a lesser degree, very thin asphalt concrete are susceptible to the cold and can facilitate the production of black ice. In France, porous pavement surfaces fall to the frost point about 30 minutes before dense surfaces.

In the event of a prolonged winter storm, salt must be supplemented by a calcium chloride solution to remove thick ice and snowpack from the spaces in the porous surface. In France, a combination of dry salt, wet salt, wet salt enhanced with calcium, and straight calcium chloride solution is used, depending on pavement conditions (ice versus snow), preventive-versus-reactive maintenance, and wet-versus-dry surface.

In Italy, 34 percent of the Autostrade system has PA. To date, the Italians’ experience with PA has been good, but they have experienced clogging issues with various types of porous pavements. Attempts to clean porous pavements have not been beneficial and the noise-reduction capability of the pavement has been reduced. However, the Italians indicated they have developed a new machine that allows them to thoroughly clean the pavements, which they plan to do every 2 years. Mill and overlay is the typical method for replacing the porous surfaces.

The Italians reported up to a 50 percent increase in salt use for porous pavements in the winter. The typical combination used is magnesium and calcium. In Italy, runoff of the salt brine is an environmental concern.

The British prefer thin, noise-reducing surfacings to PA surfaces. Their experiences with PAs in the 1980s indicated these tended to clog even on high-speed motorways and were also subject to raveling after a fairly short life. Less winter salt is required for the thin surfacing because the texture of the pavement holds the salt on the road surface for a longer time period. With open-textured PA, much of the salt disappeared into the voids below the surface.

In the United Kingdom, pavement management (PM) drives the delivery needs. The target is to cover 60 percent of the system within 10 years. The British estimate this will benefit three million people living within about 500 m of the strategic network. To accomplish this goal will require the overlay of 2,000 lane/km per year. A budget of ₤700 million per year is dedicated to covering network maintenance costs.

| << Previous | Contents | >> Next |