U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

One of the most important aspects of the scan team's experience is that we learned what we in the U.S. could do better, and we learned what we should do together globally.

—Debra Elston, Scan Team Cochair

During the early days of the scan, the team approached gathering its findings in a segmented manner—looking at the important information discussed and exchanged organized by country and then by each of the primary themes. As the scan progressed, the significant aspects of the thematic areas emerged, forming a body of information for consideration of its applicability to U.S. research program administrative policies and practices. This chapter discusses the key findings of the team organized by the four primary themes of interest.

The transport research agenda is closely related to visions of society development, global competitiveness, citizen and company needs, [and] political government programs.(2)

—Matti Roine, Chief Research Scientist, VTT

Areas of interest within the research framework theme span subthemes such as identification and scope of the research frameworks, addressing consensus, and elements of program portfolios. Issues dealing with national policy and direction as well economic position were also important topics of consideration.

Transportation research is directly related to national economic growth and competitiveness. In every country visited, the prevalent belief was that "if you aren't doing transportation R&D, then you won't be globally competitive." The international counterparts appreciated their R&D activities in the context of the entire world. Their perspective on transportation research differed greatly from the U.S. public sector model; the host countries saw research as an essential piece of their efforts to maintain or create a more robust national economy. Individually as well as collectively through the European Union, European countries clearly saw a role for transportation and infrastructure research activities as a major avenue to achieve a higher global competitive stance. They viewed the outcome of research as an economic stimulus to start new businesses and increase economic growth.

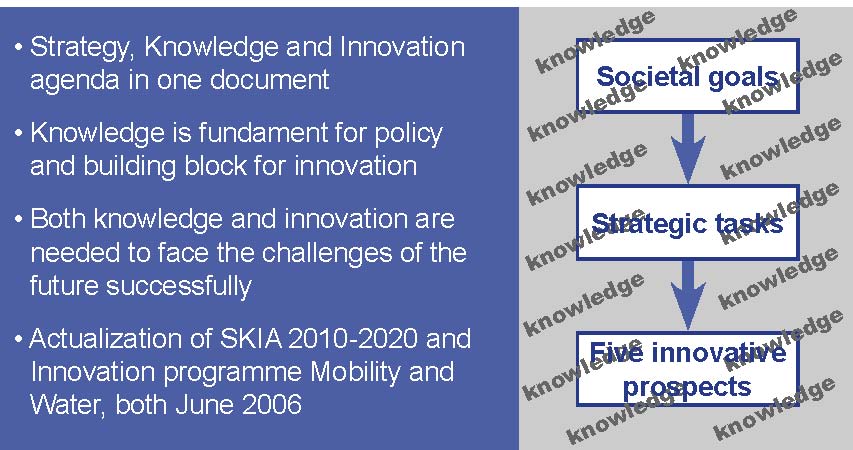

For example, the European Research Area (ERA), a European Commission program, is using knowledge as its basic building block to achieve leadership for Europe (figure 1). This knowledge-based society is created through a strong triangle of research, education, and innovation. These three aspects of science and technology produce sustainable growth and employment. Transportation research is an integral part of ERA and is continually associated with the opportunities and vision for producing economic advantage for Europe.(3)

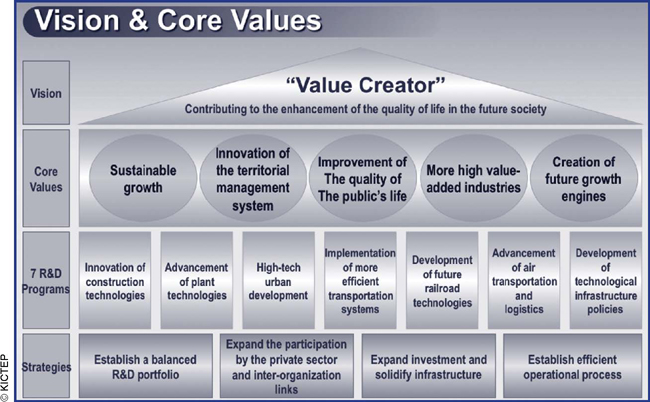

South Korea and Japan, while expressing the economic competitive stance in different terms (such as "for societal good"), were well aware of the powerful relationship between research outcomes and creating economic value. In fact, creating value and quality of life enhancements in both countries was a commonly expressed goal of transportation research. The vision for KICTEP's long-term plan is "contributing to the enhancement of the quality of life in the future society." In figure 3, societal benefit is a core value expressed in terms of sustainable growth, more high-value-added industries, and creation of future growth engines. Similarly, long-term strategic objectives of the KICT include building a safe social infrastructure and using land and resources efficiently.(4)

Figure 1. European Commission research is integral to economic growth, creating knowledge-based leadership.

Moreover, every country visited had recent legislation for research and technology efforts, which addressed more clearly the issue of transportation R&D value and its direct relationship to economic advantage. Certainly, the concept of transportation R&D as a lever to create value for the economy was a dominant concern.

Strategic and policy-driven frameworks for transportation research are the standard. The scan team found that in the countries it visited transportation research frameworks are developed nationally through a strategic process closely tied to national policy goals and objectives. These research frameworks include broad societal issues, and transportation is a primary focus area integrated with other topics to address national concerns. In nearly every country, the effort committed to preparing and using a national research framework was notable. In conjunction with the national perspective, a number of countries, especially in Europe, have well-defined mechanisms to incorporate the country's operational and user needs into the framework.

Comprehensive planning and identification of a European research agenda by the European Commission benefits Sweden, which incorporates and uses as a guide the ERA agenda for determining where it will direct its research resources. The Swedish Road Administration cites three basic principles that link its work to the European research framework(5) :

Particularly exemplary are the activities the Rijkswaterstaat Transport and Navigation Department (DVS) in the Netherlands performs. DVS uses an integrated Strategy, Knowledge, and Innovation Agenda (SKIA), which is used throughout the Dutch Ministry of Transport, Public Works, and Water Management. (See figure 2.) "Given the close connection between knowledge and innovation, and the importance of both for policy, implementation, and supervision, both knowledge and innovation [are] incorporated into one agenda." Both knowledge and innovation are required to "realize the future societal challenges against acceptable costs . . . action is required now in order to be prepared for the future. Therefore: start 'thinking for tomorrow' today."(6) The process for defining a research framework at DVS involves a top-down approach fused with strong bottom-up input. Corporate considerations linked to policy outcomes are incorporated with regional experiences and linked to daily operations. Workshops with a broad reach in the organization are conducted to facilitate the identification of research program portfolios and topics of importance to the field organizations.

Figure 2. The Netherlands DVS integrated Strategy, Knowledge, and Innovation Agenda.

©Dutch Ministry of Transport, Public Works, and Water Management

Other countries' framework development models included multitiered strategic planning activities. France develops a medium-term plan that includes its strategic priorities for a 4-year period. The example provided to the scan team included five thematic priorities (each having a corresponding research program) in the medium-term plan, each priority having about 10 research areas and each area having three to four topics yielding 150 to 200 research problems. Top-down strategic orientation is used to accomplish this planning process, but bottom-up origination proposals are received for describing and conducting the research.

Figure 3. KICTEP research framework development: long-term plan (innovation roadmap) creating value.

The example of a model transportation research framework shown at the KICTEP was a process established through formalized strategic planning. There were some similarities to the French system, such as meshing top-down guidance for long-term strategic direction with bottom-up response for midterm project identification. For KICTEP, planning processes were very well defined.(7) KICTEP's strategic approach includes a long-term planning process (innovation roadmap) leading to its "value creator" vision, as shown in figure 3. The ultimate vision is to seek enhancement of the societal good. To reach this vision, core values are integral. They include comprehensive areas that address providing sustainable, economic, and quality benefits; management excellence; and a focus on future growth. KICTEP uses seven R&D programs to achieve its value contribution. Programs focus on topics such as innovation of construction technologies, implementation of more efficient transportation systems, and development of technological infrastructure policies. These programs are developed by incorporating strategic needs and including continuity with existing projects, ministerial cooperation, technology trends, and private and public sector demands. Furthermore, strategies that allow accomplishment of these programs are establishment of a balanced R&D portfolio, expanded participation by stakeholders, expanded investment in infrastructure, and efficiencies in operation. Elements of this long-term planning process are familiar to U.S. transportation research managers. However, a key to the success of the KICTEP model is the level of commitment to developing a process, assuring that the process serves the organization well and that the process provides integration with the national strategic framework.

The long-term plan or innovation roadmap is one part of the planning process that enables KICTEP to contribute to the national strategic framework. KICTEP assesses the national R&D policy against its construction and transportation R&D policy every 5 years. For its program response, KICTEP develops a long-term plan every 10 years (with periodic assessments during the 10-year timeframe). A midterm plan is developed every 5 years, and action plans and project plans are developed annually. The process is detailed and comprehensive and allows the organization to contribute effectively to national priorities.

Exemplary research frameworks are accompanied by well-defined processes to create comprehensive transportation research roadmaps. The Netherlands and South Korea are excellent examples of how expertise in developing research frameworks affects downstream processes, such as fostering comprehensive roadmaps for determining effective research programs. To show the widespread application of this finding, however, another example from Japan is useful. The Japanese MLIT uses a highly developed process to determine its research framework and projects for research. The outcome of the process is the MLIT Technology Basic Plan (currently for 2008-2012).(8)

MLIT's Technology Basic Plan uses as guidance the Japanese Cabinet-adopted "Long-Term Strategy Guideline," which provides the following society-wide objectives:

Further input to the Technology Basic Plan is provided through an Innovation Promotion Outline, also adopted at the national level. Items in the outline that address infrastructure include the following:

The Technology Basic Plan is a component of the country's Science and Technology Basic Plan— the national research framework.

The Technology Basic Plan is developed by technology working groups of councils established through law. These working groups seek input by analyzing prior plans and activities; surveying regional organizations, research institutions, private sector organizations, and industry groups; and conducting management of technology and R&D workshops that incorporate perspectives of academic experts and other private sector participants. The output of the working groups is consistent with other government plans, such as those provided for infrastructure development. As with other plans, the Technology Basic Plan receives public comment.

The current Technology Basic Plan identifies eight problems requiring urgent attention:

Using these identified problems and societal aims, officials develop R&D priorities that give R&D results back to society, establish a common foundation for innovation, and provide international contribution. The plan continues to detail measures to assure these three priorities are achieved. Additional information about the plan is in this section under the Conduct of Research theme.

All of the research projects that we undertake concern policy issues relevant to actual societal needs.(9)

—Professor Dr. Shigeru Morichi, President, Institute for Transport Policy Studies

The countries had an ability to align the transportation research framework with a common vision. In addition to a clear and purposeful approach to establishing strategic frameworks, the countries demonstrated a notable focus on communicating the frameworks to stakeholders, including the public. For European countries, the strategic framework developed for transportation research at the EU level was fully understood and incorporated as part of the vision and mission for the individual EU countries visited.(10) In Sweden the scan team heard that "there is a common view shared in Europe on how European roads and road transport should be developed, [and] Sweden has adopted the European way ahead for the renewal of roads and road transport."(11)

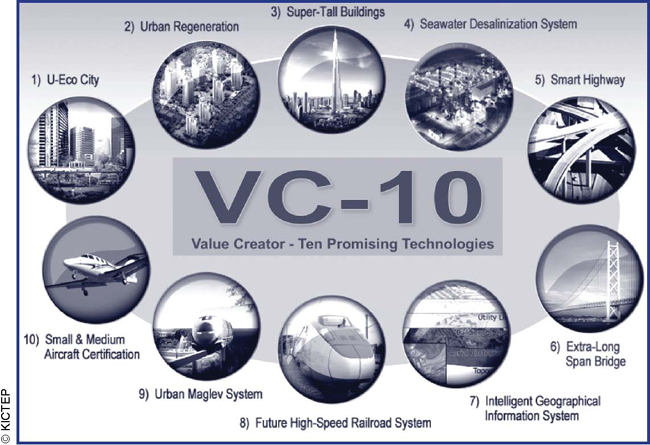

Figure 4. KICTEP developed 10 promising technologies aligned with common vision.

For KICTEP, the common vision of the national research framework extends deeply into the program portfolio and project definition aspects of its research planning process (see figure 4). Twenty strategic projects are identified that lead to the development of 10 promising technologies. The process through which these projects and technologies are identified reaches broadly throughout the transportation community, including expert workshops and government council participation. The 10 promising technologies focus on creating value to enhance of the quality of life in the future society.

South Korea and Japan have a unique cultural emphasis on the coordinated society, which helps communicate the framework to support a common vision for research activities.(12) Japan places a great deal of emphasis on responsibility to society, trust, and regard of traditions, which may make it easier to create and accomplish research based on common vision. The Public Research Institute of Japan (PRWI) articulates its research philosophy as follows:

All of the host countries give a great deal of attention to assuring the vision is communicated well and owned by all stakeholders. They do it through effective planning and extensive incorporation of industry and academia in building the common vision and accomplishing the research activities. The main drivers are societal rather than industrial goals, using transportation to improve the quality of life.

The issue of common vision also is evident in the way the various modes and elements of the transportation industry are brought together to perform R&D efforts. In the European host countries (France, for example) the vision for transportation research was to solve larger issues—such as reinventing the city, climate change, or creating knowledge for economic advancement—thus bringing autos, trucks, roads, safety, environment, technology, private sector, quasi-public and public sectors, academia, and other areas together to work on the problems at hand. In the Seventh Framework Program (FP7), the European Union's comprehensive research initiative for reaching growth, competitiveness, and employment goals, the research subtheme on sustainable surface transportation includes activities that address environmental concerns, congestion and mobility, safety, and the economy. (see box below)

| EU Seventh Framework Program Research Activities Subtheme: Sustainable Surface Transport |

|---|

|

Senior-level individuals frequently emerge as visionaries or champions and play an instrumental role in national program focus and support. In a number of the entities and host countries visited, such as the European Union and Japan, senior experts who have earned a respected place in the transportation community are often regarded as highly credible opinion leaders on a national level. These influential individuals are likely directors of R&D institutes, provide counsel to government and joint research activities through personal contact and various organizations, and possess extensive networks through which they operate. Because of their positions, expertise, and contact with a wide network, these senior-level people also serve as champions for unique research issues, advancing research in a way that attracts financial resources, technical expertise, and political influence. The noteworthy aspect of these individuals is their access to national policy formulation and decisionimaking. The scan team observed that the accurate and expert transportation R&D knowledge these champions provide to national leaders is a key factor in a country's support of the necessity for and value of R&D efforts.

One of the best examples is the role, accomplishments, and valuable contribution made by the president of ITPS in Japan. This highly respected professional works within a broad network that includes academia, government councils, semipublic organizations (foundations), private sector entities, and transportation and policy institutes. His knowledge of the transportation arena is often sought by national policy figures. His expertise and support from the institute and others provide Japan's leaders with reliable, high-quality information that enables them to make effective decisions.

National research frameworks had common topics in many of the host countries, and these frameworks are being addressed by cross-ministerial R&D activities.

It is understandable that many of the European countries had common topics for their national research framework. Considerable effort has been made by the European Union to reach consensus and communicate the common themes to the member countries. The host countries' national frameworks had a remarkable series of topics that were independent of country or location, yet were highly relevant to each country. Problems included in national frameworks tended to be global concerns as well as country concerns. Many issues articulated in Europe were also important to Japan and South Korea:

Not only were most of these framework topics brought up in individual country contexts, but solutions to these vitally important national issues were also being addressed by broad resources in the countries. National problems were being solved by incorporating extensive cross-ministerial bodies that include land, infrastructure, energy, environment, culture, and sports, for example. In some countries, the primary ministry that sponsored transportation research incorporated the wider perspective. In France, the LCPC is a state-owned institute under the authority of two ministries, including the Ministry for Ecology, Energy, Sustainable Development, and Spatial Planning. In Japan, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism incorporates surface and air transportation as well as land use and other infrastructure topics.

The value of having cross-ministerial or cross-functional organizational structures perform transportation research is that they bring a greater body of resources to finding transportation solutions. Transportation problems include not only facilities and infrastructure, but also energy, ecology, mobility, and land use. The scan team found that many countries address national priorities in such a comprehensive manner.

It was evident that topics of concern in the international transportation research community are also of concern to U.S. researchers. The United States has many opportunities to initiate joint efforts to solve some of these pressing problems. Furthermore, there are excellent examples of the use of multi-or cross-discipline sponsors and resources for transportation research activities for the United States to consider.

In the host countries, transportation research partnerships and joint research efforts are essential, ubiquitous, and actively promoted. The role and use of partnerships and the collaboration of multiple players are integral elements of the research activities in the various countries visited. For Europe, the effort of creating a single economic market is a catalyst for fostering joint research. The European FP7 research activities spawned a number of independently formed venues for collaboration, including ERTRAC and ECTRI. Furthermore, there is a strong sense of "we know we can't do all this separately," and organizations such as the FEHRL are actively promoting the attractiveness and effectiveness of stewardship and leveraging of resources for all research processes (program portfolio content to implementation and deployment).

Typical partnership concepts in use in Europe are as follows:

| Maximum reimbursement | RDT activities |

Demonstration activities |

Management of consortium/ other activities |

|

| Collaborative project | 50 75 |

50

|

100

|

non-profit academic & research organizations SMEs security related research (in certain cases) |

| Coordination & support action | 100 | |||

| Network of excellence | 50 75 |

|

100

|

© ECTR Figure 5. EU funding levels vary depending on type of R&D partner.

Host countries' transportation R&D collaboration activities begin substantially further upstream than in the united states. Research programs in host countries incorporated academic and industry participation in research activities earlier in the research process than in the United States. In the host countries, collaboration flows throughout the research process—from problem definition (which may include participation in establishing the research framework) through the conduct of the research and the delivery of research products. All programs reviewed had more integration among the various elements of the research process than in the United States. U.S. research activities tend to be divided into discrete elements (e.g., problem definition, researcher selection, conduct of research, technology transfer and implementation, and full deployment). U.S. research administrators are tempted to involve partners only in the later research processes, such as implementation activities or deployment. In the host countries, industry and academia were integral to the problem definition and worked in conjunction with research administration throughout the research effort, accruing numerous benefits to host country programs. For example, in some host countries, the early incorporation of academia provided added potential for the research to develop knowledge as well as provide resources to build workforce capacity for sustainable economies and global competition. Likewise, the integration of industry early in the process confirmed that research is a factor in growing national income-generation opportunities. Host countries noted that academia provided knowledge creation and industry provided knowledge application. Encouraging these collaborative activities early in the research process enables a more robust result with a higher likelihood of producing benefits.

Research institutes are an important vehicle for exercising transportation partnerships and collaboration. Without exception, each host country had some form of research institute that is a primary vehicle to either fund and financially manage or foster, house, and accomplish collaborative research efforts. The formation and structure of the research institutes varied from country to country, but each brought together government, quasi-government organizations, foundations, government-funded independent organizations, academia, and industry to more effectively respond to the national strategic framework than each organization could on its own. Institutes often were the venues bringing together the responsibilities for knowledge creation, knowledge management, and knowledge application aspects of R&D. In a number of instances, R&D collaboration is written into law, facilitating industry, university, and government collaboration. The United States does not have comparable unique entities to facilitate collaborative research on this level. Some U.S. structures can accomplish portions of the roles of these institutes, but integration of the various responsibilities in one institutional structure is clearly a non-U.S. model.

An example of the use of institutes is LCPC, which facilitates partnerships with the French National Research Agency, universities, and industry for precompetitive research (research on topics that are not product specific or that have no identified industrial application or capability for commercial exploitation), for research calls by the EU framework program, and for work with FEHRL and other European technology platforms such as ERTRAC (private sector). LCPC promotes research pools of expertise to address research topics, executes memoranda of understanding (MOUs) to accomplish research domestically and internationally, and promotes activities of the Centers for Competitive Capacity, a multipartner R&D effort.

The French commitment to research partnerships extends also to a premier institute structure, the Carnot Institute network. This network includes 13,000 researchers at 33 member institutes, such as the INRETS, located throughout France. The "Carnot" label connotes research partnerships to foster innovation and competitiveness for major economic and social challenges. The Carnot Institute network competencies address seven major themes, one of which is environment, energy, propulsion (including transport), and chemistry. The institute structure is one of the largest European research and technology organization collaborations. The Carnot Institute network and the institute structures in Sweden, Japan, and South Korea, for example, clearly demonstrate the value placed by host countries on this organizational arrangement to accomplish effective transportation R&D.

An important role for research institutes was fostering coordination of research activities and programs. Frequently, the institute structure allowed experts on a topic to come together and provided a forum to advance research efforts, more effectively use resources, and prevent duplication of effort. In addition, research institutes often incorporated private sector organizations that were essential to the research problem design and research conduct and well positioned to put the research results into practice. The Safer Vehicle and Traffic Safety Center in Chalmers, Sweden, is a consortium institution with 22 partners, including the Swedish Road Administration, the University of Gothenburg, vehicle manufacturers, transportation institutes, and other private sector technology organizations. Safer is a joint research unit with a physical location, staff resources, and equipment, but it is not an entity of any of the member organizations. Funding sources are one-third government, one-third university, and one-third private sector. Partners provided a 10-year commitment—2006-2016—to accomplish research.

Institute structures like Safer also focus on innovation. The structural organization of an institute is designed by an agreement that is workable for all parties. Often such flexibility in structure allows greater diversity of partners and provides for a greater level of expertise and resources to solve difficult problems. With commitments for funding stability and long-term research efforts, institutes often were formed to produce innovation or leaps in technology rather than small, incremental steps that may come from isolated research project efforts.

Another example of the usefulness of institutes is the KICT experience with exchange agreements with 37 organizations, including the Republic of Korea Air Force, the Korea Institute of Industrial Technology, and the Incheon Free Economic Zone. The institute makes its resources available, including opening its laboratories to construction specialists and students, as part of its role as a learning center that combines classroom theory with field-based research.(14)

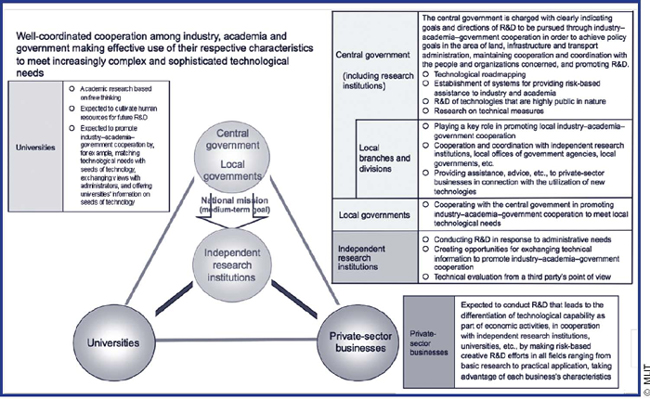

An example of the central role of institutes in accomplishing research is illustrated in figure 6 from MLIT in Japan.(15) A similar model was used in myriad contexts at host organizations. Each of the three partners of the institute has specific roles and responsibilities. In the MLIT model, universities bring unbiased thought and research capacity, can develop future workforce skills, and are vehicles to promote cooperation; private sector members bring the perspective of economic advantage to the research efforts; and government at various levels sets direction and policy, assists in research results implementation, and provides a link to other necessary government entities. Independent research institutes take the responsibilities of the partners and add their capabilities to conduct research; promote cooperation among the government, industry, and academic partners; and provide an essential third-party perspective for evaluation.

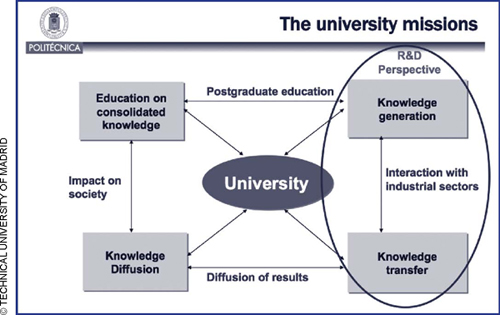

Academic partners are integral to transportation research performance. In every host country, academic partners in transportation R&D had a more integral and integrated role in research activities than seen in comparable U.S. research efforts. In Europe, academics were always incorporated into an innovation group that also could include industry, government, and policy players, whether the structural organization was a research institute or other form of research partnership. The situation was similar in the Japanese research institutes model. Furthermore, the contribution of academic partners in generating and transferring knowledge was seen as a significantly more important outcome of transportation research partnerships than experienced in U.S. public sector transportation research efforts. Figure 7 (see below) is an illustration from the Technical University of Madrid, an ECTRI member, showing the role of the academic partner in R&D, particularly in interacting with the industrial sector.(16) This university is also a participant in EU FP7 activities, which may fund some of the research this figure models. Note the university mission is related to knowledge. Knowledge is developed through R&D and transferred to users for economic advantage. Knowledge is used to build greater knowledge and impact society.

Figure 6. Institute model: industry-academia-government relationship in R&D at MLIT in Japan.

Figure 7. Technical University of Madrid academic role in R&D.

When officials discussed academic expertise during the scan meetings, they mentioned the multiple benefits the academic sector brought to the research effort. Academic partners participated in determining research framework priorities, created knowledge through R&D, provided unbiased third-party assessment and evaluation, helped create the future workforce, and provided advantage for the economy.

International research partnership models in transportation are similar to models used in the United States. The scan team found similarities in the models for partnerships used by its international counterparts. In fact, it was encouraging to see the operation of partnership models in the various international contexts because these similarities showed potential for future partnership and collaborative activities for U.S.-international research efforts. While some aspects of international partnerships were familiar, others provided learning opportunities for the team.

VINNOVA, the Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems, exhibits a center of excellence model for accomplishing collaborative research.(17) The VINN Centers of Excellence provide a forum for collaboration among the private and public sectors, universities and colleges, research institutes, and other organizations that conduct research. The centers deal with both basic and applied research and work to ensure that new knowledge and technological developments lead to new products, processes, and services. The following are major characteristics of the centers:

Many of these characteristics are familiar to U.S. transportation research administrators. However, a few items, such as a focus on international research leadership and long-term sustainability, may be areas for further investigation for application to U.S. programs.

Four collaboration models identified by the European Research Area Network for Roads (ERA-NET Roads)(18) are another example of successful partnerships. These models address the lowest to highest levels of cooperation:

Elements of these models are found in various U.S. R&D activities, but aspects of framework creation, work sharing, and financing continue to present challenges to some. Further investigation of international programs' partnership practices will be beneficial to U.S. transportation research programs.

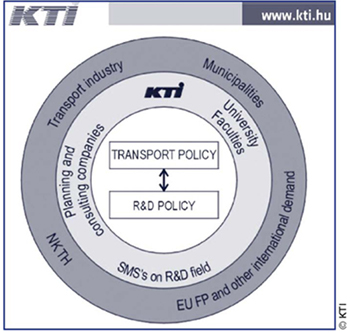

A typical model of research partnerships found during the scan is Hungary's transport R&D model, shown in figure 8. Like others, the roles of government, industry, and academia are essential. In this model, industry, municipalities, the national office for research and innovation, and international research programs all interface with those performing research, KTI, the Institute of Transport Sciences, universities, consulting organizations, and SMEs in the R&D field. The performance of research focuses on a two-faceted center, transportation policy and R&D policy.

Figure 8. Transport R&D model in Hungary.

Similarities in partnership models also extended to the types of partners. In many countries, strong partnerships exist with automotive manufacturers. For Sweden, the automotive industry is the top exporter, and in keeping with its focus on maintaining economic competitiveness Sweden has a model partnership program—the Swedish Automotive Research Program.(19) This program subscribes to the Swedish goal of "Vision Zero" for road fatalities and strictly adheres to European emissions standards. The partnership includes truck manufacturers (Volvo and Scania) as well as premium auto manufacturers (Volvo and SAAB). The research partnership's annual budget is $200 million, a substantial growth since its 1994 inception. The program's administrative organization includes an independent state-appointed chair, the secretariat at VINNOVA, and a cooperative agreement among government agencies and industry. Similar to other research initiatives in Sweden, the program negotiates long-term agreements between government and industry; ensures strong industry involvement for framework development, creating research agendas, and project selection; operates with a small central staff; and fosters continual improvement through program evaluations.

Like Sweden, many countries have active collaborative arrangements with the automotive industry for initiatives in intelligent transportation systems (ITS) and other precompetitive automotive research efforts, such as Japan's government partnership activities with Mitsubishi.

USA partners are very rare up to now; American participation in [European Union] Framework Programs would be very useful.

—Andres Monzon, ECTRI

DVS wants to be a leading expert, a smart buyer, and knowledge chain director.(20)

—Rudd Smit, Center for Transport and Navigation, DVS

Transportation R&D is accepted as a valuable contribution to the national or societal good. Transportation research programs and their outcomes are seen in the host countries as an important contribution to society. In fact, R&D activities are directly associated with value creation. That value may be the vision KICTEP expresses in "contributing to the enhancement of the quality of life in the future society" (figure 3), or the French research program focus on megacities and the comfort, quality, and safety of urban areas.(21) Transportation R&D is considered an economic growth generator and an essential element in global competitiveness, both in the context of large established business opportunities and the creation of startup businesses based on innovative research results. Research is also a major contributor to environmental sustainability, a critical issue on the global stage and in every host country the scan team visited. In discussions throughout the scan, transportation R&D was continually credited with providing positive impact.

Because transportation research activities were accepted as a means to achieve value, the programs reviewed did not have to continually justify expenditures, as do most U.S. research programs. In fact, the acceptance of the value of research in the host countries promotes strong research programs, which in turn develops greater value— a virtuous cycle. For example, academic partners, in particular, focus on knowledge creation and understand the contribution this makes to producing societal and economic value. Value is received through research programs that are closely aligned with priority frameworks that address essential problems for the country and society. Value is also an outcome of research collaboration, which provides for more efficient use of resources by using the unique contribution of each member of a partnership. Furthermore, the value of research is considered in the broad context of the quality of life in which benefits from transportation R&D translate into, for example, healthier and safer citizens, a cleaner environment, and sustainable economies.

International counterparts are funding transportation R&D at significantly high levels. Substantial program funding is committed to transportation research in the host countries, and in Europe the EU FP7 adds another large funding source. For the most part the transportation research programs of the host countries are more integrated into broad research arenas such as model city, urban regeneration, or impact of climate change than in the United States. Funding for transportation research in the United States is often directly linked to the specific modal area and is not integrated with larger society or economic goals. Therefore, comparisons between funding levels for transportation R&D in the United States and international programs are not easy. What can be noted, however, is the high level of funding by international programs, funding that is generally increasing to match the interest in achieving environmental and economic sustain ability and global competitiveness (e.g., KOTI reported a 60 percent budget increase over the last 3 years).

The following are representative budget figures included in scan meeting presentations:

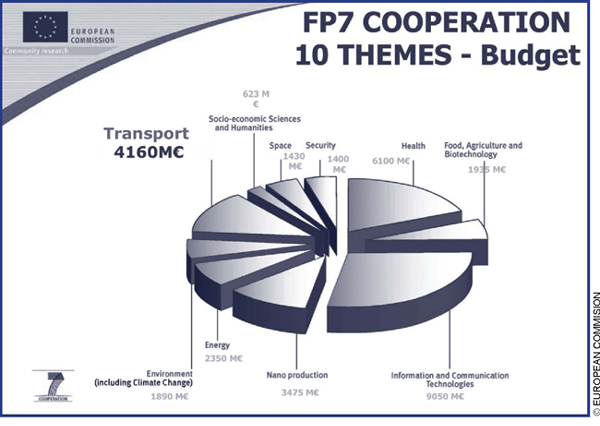

An example of the funds being committed to transportation research is shown in figure 9. This figure highlights the European Union's Seventh Framework Program (2007-2013) transportation R&D budget as a portion of the full research activities: €4.1 billion (US$6.4 billion), or 12.8 percent. The budget includes surface and air transportation R&D activities.

Program and project evaluation techniques varied in complexity and effectiveness. For the most part, every research program included some process for evaluating the results of the conduct of research. Some programs were more successful than others, and some programs were more risk adverse than others, requiring extensive review to redirect work.

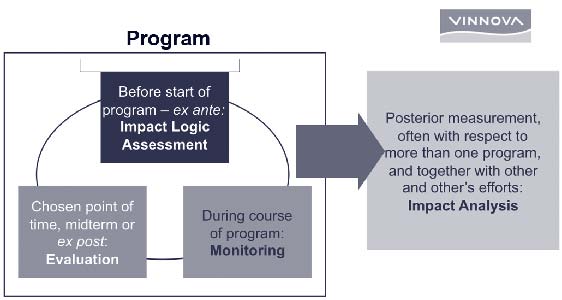

VINNOVA and KICTEP provide two examples of well-proven evaluation processes. VINNOVA conducts evaluations at a variety of stages during the research project: a preproject assessment, an evaluation during the conduct of the research (performance monitoring), an assessment at the midterm or at the completion of the research performance, and an impact analysis after implementation.(22) Its "ambitions and work [are] to understand and to increase the impact from efforts in research, innovation and sustainable growth in Sweden."(23)Evaluation of impact is accomplished at four stages during and after the conduct of research, including an impact logic assessment on the proposed research, progress monitoring during the course of the research, an evaluation of the research performed, and an impact analysis of the research results in context with other programs and research efforts. Since 2002, VINNOVA has conducted five impact analysis studies that showed a wider and deeper understanding of the R&D studies conducted, demonstrated the use of research results by industry and the public, and provided useful material for policy decision-making, such as the design of the VINN Excellence Center program in 2005.(24) (See figure 10.)

Figure 9. EU FP7 transport R&D funding.

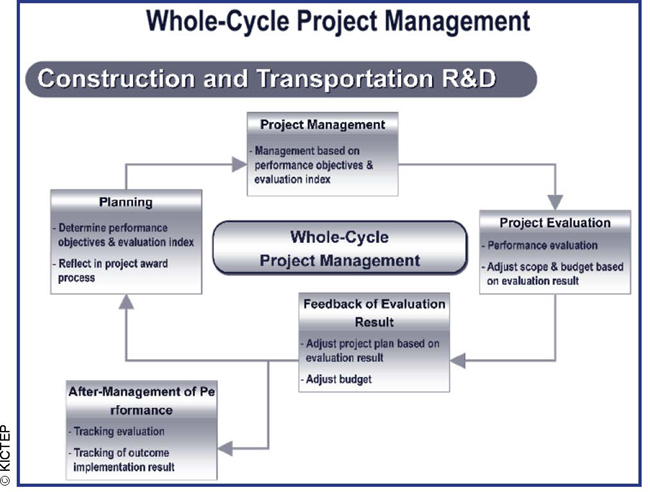

A similar example is shown in the KICTEP model for project management.(25)Project evaluation is an important aspect of the conduct of research. In figure 11 (see next page), KICTEP's concept of whole-cycle project management includes planning and developing performance objectives and evaluation indices, and managing and evaluating the project by these elements. Project scope and budgets are adjusted according to evaluation feedback and after-performance management evaluation tracking. Tracking of implementation results are included as critical to the overall whole-cycle management process.

Figure 10. VINNOVA assessment, monitoring, evaluation, and impact analysis.

Additional material provided by KICTEP also shows how integrated evaluation is to the business of research at this organization. The KICTEP evaluation process includes award review, research progress monitoring, interim evaluation, and final evaluation. A unique feature of the KICTEP performance management system is the tracking evaluation for research projects that have been completed for 2 years. The evaluation surveys the outcome application status (or determines the cause of implementation failure). It also analyzes successfully implemented projects, disseminates the successful methodology to other projects, gives incentives to outstanding researchers through awards of new projects for the next 2 years, and provides awards for outstanding researcher efforts.(26)

Figure 11. KICTEP whole-cycle project management process.

Evaluation is also an important technique included in Japan's R&D activities. The scan team received the National Guidelines for Evaluating Government-Funded R&D (tentative version, March 29, 2005), produced by the Prime Minister of Japan. This document contains comprehensive descriptions of evaluation processes for R&D. The following are some of the major topics discussed in this document:

The implementation of such evaluation processes is of interest to U.S. research managers, and further interchanges among U.S. and Japanese counterparts could provide mutually beneficial best-practice sharing.

Quantifying the benefits of research results is a continuing challenge for all host countries. As in the United States, the host countries find quantifying benefits of research activities a challenge. The efforts committed to determining the benefits varied, and no country had a completely satisfactory solution. While the information from such benefit analysis is valuable to research programs, the focus on justifying programs based on such analyses was not a critical concern for any of the countries. In fact, the value of research is fully accepted. Cost-benefit analysis in Japan, for example, was not perceived as needed or considered part of the R&D assessment processes. Because the research funding structure is changing in Japan, with organizations such as PWRI moving toward a more competitive funding process, cost-benefit issues may become more important in the future. A number of the host countries considered the United States a leader in quantifying benefits for research results. Several expressed an interest in the United States sharing the research program performance measurement tools developed through NCHRP.(27)

A variety of successful techniques and processes are potential options for consideration in the United States. The following are some of the items the scan team noted:

It is not so complicated to invent a new measure, but it is difficult to get it delivered.

—Fred Wegman, Managing Director, SWOV

Addressing intellectual property rights (iPR) is a common practice that facilitates the delivery of transportation research results. Europe has a decidedly different perspective than the United States on the ownership of intellectual property generated from government-funded transportation research. IPR is addressed before the transportation research is initiated and included in the research partnership contract. In general in Europe, development is seen as an opportunity to build a business based on the specific IP, creating an economic engine for the country. There is no barrier to government-funded organizations seeking patents. In fact, for France's LCPC, the number of patents, along with the results of application, is a performance measure used to evaluate the program.

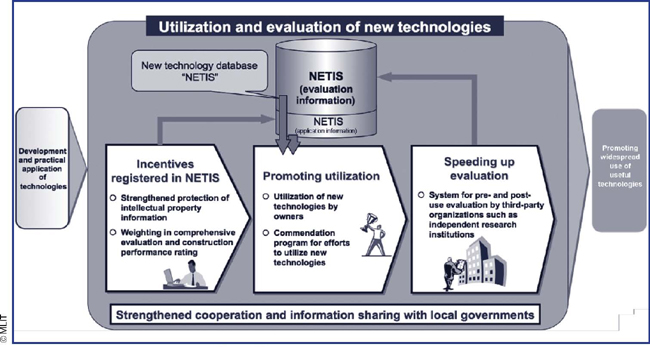

In conjunction with the intellectual property issue, an important element of Japan's MLIT Technology Basic Plan is dissemination of R&D results by tracking and facilitating use and evaluating new technologies. The New Technology Information System includes a private sector intellectual property strategy, which fosters the introduction of new technologies into public works projects and promotes R&D in the private sector. Benefits of this process include better data for use in the evaluation information system; a more robust process for promoting use of research results, new technology, or innovation; increased speed in producing evaluation results, which speeds deployment; and strengthened cooperation and information sharing with local governments, which play a large role in dissemination and deployment activities. (See figure 12 on next page.)

Japan's PWRI also tracks and uses as an indication of "practicalization" (application to practice) of its research efforts the number of patents owned and applications for patents and registrations. Fees received through ownership of intellectual property help fund the dissemination of research results. This means the direct financial benefits of the intellectual property are invested in the application of new technologies and innovations.

One item that came up in discussions with European host countries is the need for the United States to "figure out its IP issues." In particular, U.S. methods for addressing IPR for surface transportation do not fit well within the European context. This issue can be a barrier to U.S.-European collaborative activities.

Development of common platforms among u.s. and international R&D organizations will facilitate research results delivery in all countries. The development of common platforms such as linked databases or common access portals for a variety of research processes will substantially reduce barriers for R&D collaboration, foster international partnerships, and promote more widespread use of research results. Topics such as the IPR issues, sharing of research expertise for peer review activities, and development of joint databases for information exchange are just a few of the areas that could benefit from common platforms among global R&D collaborators.

Information management is a prime area for developing common platforms. Sweden's VTI Library and Information Center is already establishing contacts with the TRB Library. Items for cooperation focus on incorporating research reports into the countries' respective information databases through the use of common platforms for information sharing.(28) (See figure 13.) This collaborative effort shows great potential as a model for others to develop more tools and processes to aid in better communication and delivery of research results.

Figure 12. MLIT use and evaluation of new technologies.

| Co-operation with TRB. Ideas |

|---|

|

Figure 13. VTI's ideas to create a common platform for innovation sharing.

©VTI

Another example of where common platforms and databases may be beneficial is the Community Research and Development Information Service (CORDIS). The CORDIS Web site for science, research, and development states that it is the official information source on EU FP7 calls for proposals. It offers interactive Web facilities that link researchers, policymakers, managers, and key players in the research field. Its mission is to facilitate participation in European research activities, enhance exploitation of research results with an emphasis on sectors crucial to Europe's competitiveness, and promote dissemination of knowledge fostering innovation for enterprises and the societal acceptance of new technology. Use of CORDIS is free of charge. It makes available to its users briefing material on European innovation and research activities and stakeholders, profiles of partners to facilitate collaboration, research results services, and document library services.(29) Additional investigation of the structure, organization, and use of such a model for U.S. research activities could be helpful for domestic and international collaborative R&D.

The number of forums for international sharing of research results is increasing. ECTRI and many of the host countries identified a variety of venues and forums that exist to increase the use of research results. There were a variety of contexts within industry and the scientific community, through strategic research initiatives and political bodies, in connection with unique research themes and organizations, and based on geographic location.(30) Figure 14 lists some of the forums for sharing new research results used in ECTRI. This list is just one example of the many MOUs, agreements, research collaborations, joint partnerships, and other vehicles that have allowed diverse international partners to share and benefit from valuable research results.

| "Forums" for sharing new research results internationally |

|---|

|

Figure 14. ECTRI forums for sharing new research results internationally.

The scan team observed other examples of this type of activity in South Korea, where research institutes create forums for international sharing using workshops, showcases, and demonstration of research activities. KICT explained in one of its presentations that it had international agreements for exchange and cooperation with 24 organizations and conducted regular joint construction technology seminars with Japanese, Chinese, and Russian counterparts. International cooperation was also a focus for KOTI, which collaborates with a variety of institutes and international organizations, including the East-West Center at the Texas Transportation Institute; INRETS in France; organizations in China, Russia, and Taiwan; and international organizations such as the European Conference of Ministers of Transport and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. International academic forums are additional venues that focus on technology transfer and educational opportunities that enhance the potential for increased implementation or delivery of research results.

During the course of the scan, the team also learned of existing collaborative venues of U.S. academic and international research organizations. While these research consortia or joint efforts have been developed to create knowledge on specific topics, the associated function of disseminating research results is also a mission of the joint efforts. Most of these U.S.-international activities are only known among those directly associated with the activity or particularly informed about the research topic. Because of these and similar activities, models or networks are already established that could demonstrate methods to build capabilities and capacity for more effective dissemination of research results. More work needs to be done. Opportunities such as this scan and the implementation strategies developed from it can make a difference in the way researchers throughout the world communicate, collaborate, and benefit from the work of their international counterparts.

| << Previous | Contents | Next >> |