U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

While only a minimal number of private transportation concessions have been awarded in the United States, some of the European countries visited on the scan are leveraging concessions for major portions of their highway systems. Concession agreements typically allow the concessionaire to design, build, and operate a project, with the right to receive revenues from operations and/or to receive payments from the public agency for use of the project. The use of concessions was found in each of the countries visited on this contract administration scan tour, and included both construction and maintenance of motorways. Concession periods vary, but were commonly found to be 3 to 5 years for maintenance and 15 to 30 years for construction and operation. In France, concessions have been an integral part of its program to develop, operate, and maintain its main highways for more than 30 years. Portugal is aggressively employing concessions as part of its strategic plan to develop its national highway system, and plans to have 90 percent of its national highway system administered by concessions by 2006. The United Kingdom has begun an aggressive DBFO plan as part of its national PFI, with commitments or plans for more than 15 projects to date. The Netherlands has embarked on limited use of concessions, primarily on tunnel and rail projects, and is experimenting with concessions for smaller maintenance and operations contracts.

The main reasons for using concession range from a lack of public funding to a belief that private financing and delivery provides a higher quality. Concessions also are being used as a means to provide benchmarks for public-sector agency performance. As discussed throughout this report, many European highways agencies are beginning to take the role of network operator rather than provider of services, which leads to an outsourcing of production tasks through concession contracts.

Concession contracts can take many forms, and the definition of a concession contract can vary slightly from agency to agency. For purposes of this report, the definition of a concession contract will be taken from A Draft Typology of Public-Private Partnerships as written by Rémy Prud'homme for the French Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Housing (Perrot and Chatelus 2000):

The concessionaire carries out all of the capital investment, operates the resulting service and is remunerated through service fees paid by users. The facilities are to be handed over to the oversight public authority at the end of the contract period.

Concession contracts are interrelated with alternative finance, as discussed in Chapter 6. Concessions are procured and administered using the contracting techniques described in Chapter 3 and have many of the same characteristics as the DBOM contracts described in Chapter 4. These contracts also implement the performance contracting techniques described in Chapter 5. Because the use of concession contracts is so prevalent in Europe, the scan team decided to devote a full chapter to concessions instead of trying to address them on a piecemeal basis.

The table on the next page is provided to help clarify the differences between

concessions and other PPPs. The options in column one of the table below provide

the spectrum of PPPs from traditional agency management to complete privatization.

The table was adapted from A Draft Typology of Public-Private Partnerships as written by Rémy Prud'homme (Perrot and Chatelus 2000).

| Option | Capital Investment | Operation & Maintenance | Commercial Risk | Asset Ownership | Contract Period | Discussed in Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Agency Management | Public | Public | Public | Public | - | - |

| Service Contract (Performance Contracting) | Public | Public/Private | Public | Public | 1 to 2 years | Chapter 5: Performance Contracting |

| Management Contract | Public | Private | Public | Public | 3 to 5 years | Chapter 3: Contracting Techniques |

| Concession of Existing Network | Private | Private | Private | Public | 5 to 30 years | Chapter 7: Concessions |

| Concession of New Facility (Build, Operate, Transfer) | Private | Private | Private | Public => Private | 20 to 30 years | Chapter 7: Concessions |

| Privatization | Private | Private | Private | Private | Indefinite | Not Discussed |

Since many of the contract administration features of concessions are discussed in other chapters of the report, this chapter presents successful concessions case studies and valuable tools discovered on this scanning tour. Specifically, the incorporation of concessions into strategic plans for road networks is discussed via profiles of the Portuguese and French approach to network concessions. The selection of concessionaires is discussed using examples of the Portuguese approach and the Public-Private Comparator utilized by the British and Dutch Highways Agencies. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the duration of concessions and measures of performance to ensure quality during concessions.

Through establishment of a partnership between the public and private sectors, concessions can be an effective means of satisfying the strategic needs of highway transportation agencies. Transportation projects involve a very high level of capital investment combined with an extremely long period for recovery of this investment. Additionally, forecasting the rate of payback is extremely difficult because of the number of variables that affect use of roadways, including the variety of transportation options available to users (alternative routes, mass transportation, etc.). Given the critical need for transportation infrastructure to support movement of goods and people, and the lack of inherent incentives for the private sector to provide highways, one of the traditional roles of government has been the delivery of public highways. In some European countries, however, there is a belief that the private sector can provide the same services at a higher quality and lower cost. In other countries, the public sector is not capable of or is not willing to make the financial investment required to complete major infrastructure projects. These are just some of the reasons for use of concession contracts as a part of highways agencies' long-term strategic network plans.

Of the countries visited on the scan, France and Portugal are the most aggressive users of concessions. They view their concessionaires as an extension of the highways agencies. In France, only one of the nine concession companies is wholly privately owned. In Portugal, 90 percent of the strategic National Road Plan will be under concession by 2006. In these countries there is a belief that concessions will deliver a better value for each Euro spent. The following table lists the financial and political advantages to the government of using concessions. The table was adapted from In Favor of a Pragmatic Approach Towards Public-Private Partnership as written by Corinne Namblard (Perrot and Chatelus 2000).

| Financial Advantages | Economic & Social Advantages | Political Advantages |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Given the advantages listed above and other realities of each country, Portugal and France have turned to concessions as the primary method for implementing their national road plans. The following sections outline the specific use of these concessions in each country.

The

Portuguese Strategic Plan

The

Portuguese Strategic Plan To meet its program goals quickly and efficiently, the Portuguese Highways Agency, Instituto das Estratas de Portugal (IEP), has made major changes in its methods of doing business over the past few years. In 1991 Portugal's roadway network included only 431 km of concessions. By 2006 it plans to have a total of 2,700 km of concessions in place--representing 90 percent of its national highway network. Use of a concession system is allowing Portugal to complete its strategic National Road Plan in 2006 - 8 years earlier than the schedule using traditional methods.

The Portuguese use two primary payment vehicles for their concession contracts. The first means is real tolls such as those being used for U.S. concessions. Concessionaires finance and maintain the roadway in return for payments collected as tolls from roadway users. The second means of payment is through shadow tolls where the government pays fees to the concessionaire on the basis of the number of vehicles using the roadway. Shadow tolls are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6: Alternative Financing.

The primary driver for the Portuguese concession plan was Portugal's entry into the EU and the need to strengthen its trading ability. The following paragraphs are adapted from Motorway Concessions in Portugal as written by Prof. Antonio Lamas, Director of the Portuguese Roads Authority (MES 1999).

A bit of history is necessary to explain the present Portuguese "cycle" of motorway concessions. The first concession for the building of a tolled motorway network dates from 1972, with the creation of the private company BRISA to which it was granted. Shortly after the 1974 revolution, the majority part of the capital of BRISA was taken by the Government, and it became practically a public company. The rules originally set for granting a tolled motorway concession were simple but very exigent: it was required that an alternative route of good quality existed. This rule is still considered and is one of the reasons behind the decision of using shadow toll methods for the cases where no good alternatives exist and a motorway is the best immediate solution. Financially, the State budget could contribute to the initial investment up to 35% and to the economical equilibrium of the concession. The management of this concession was thus shared between the Roads Authority, representing the Minister of Public Works, and the Minister of Finances, introducing a style of regulation of the technical aspects separated from the financial matters, which still persists.

Historically, Portugal has followed the other European countries in conceding emerging public services, with a peak during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. In the main cities, almost all utilities were concessioned to private companies. Some lasted almost a century: gas, electricity, telephones, water, trains and other public transports, etc. The nationalization of several concessions and the legal closing of most public services to private enterprise, was only terminated this decade, and the consequences of this policy in the Portuguese experience, or lack of experience, in the role of concessions was serious. One of the consequences was the generalized idea that the only source of funding for public services was the budget as a generalized effort of all taxpayers, and there was no adaptation to the modern thought of preferably calling the users to fund the required investments in new and modern utilities. It is a problem similar to that faced by countries that have a tradition of not tolling roads.

For the new bridge over the Tagus River in Lisbon, Ponte Vasco da Gama, which opened for the Lisbon 1998 EXPO, a complex project finance concession scheme was devised. The same happened in the field of motorways: the limits of the concession of BRISA were redefined--that is, from being the concessionaire of "all" motorways, BRISA was limited to some main axis (with a length of 1180km) and privatized. BRISA still is one of the largest road concessionaires in Europe. At the same time, the present Government decided to open the sector to competition in order to complete, in a shorter period, the building of the planned motorway network, which is essential for the equilibrium between regions and for the access to Europe (during the almost 20 years up to 1997, the sole concessionaire built only 680km). But it has to be said that the acceptance of the need for calling private funding into the financing of expensive roads was not accompanied by a corresponding development of the acceptance of tolled roads. And strong movements against new tolled roads have emerged all over the country: the Portuguese have accepted that the main axis that was part of the concession of BRISA could be tolled but not the new ones. Not because they are considered less important but because they were not expected and there has been insufficient discussion of the principles and usefulness of new concessions. This is not simply a Portuguese problem but it is necessary to take it into consideration in order to explain the context in which, for some of the new cases, the adoption of the DBFO system with shadow or virtual tolls (which is being translated in Portugal as SCUT) took place. It can be said that it was introduced in all situations in which a motorway was required and there was no good quality alternative, or the traffic forecast was not considered to be interesting enough as to bring sufficient competition between bidders.

In

a concessions strategy such as that developed by the Portuguese, appropriate

risk allocation is essential. The adjacent table describes the distribution

for the responsibility associated with the risks of the strategic plan.

In

a concessions strategy such as that developed by the Portuguese, appropriate

risk allocation is essential. The adjacent table describes the distribution

for the responsibility associated with the risks of the strategic plan.

The risk-control strategy suggests that the party best able to manage the risk bears it. For example, the risk of planning remains with the government. The risks associated with design, construction, operation and maintenance, latent defects, and legislation are assigned to the concessionaire, while there is a shared responsibility for environmental, land acquisition, and force majeure events. There is a shared risk for revenue in the shadow toll method. Planning is the only risk that the government maintains in full.

Two of the most difficult risks affecting transportation projects are environmental permitting and right-of-way acquisition. Based on current experience, the IEP's preference is to obtain environmental approval before launching its program, but it is not always politically possible. An alternative is to have the government retain the risk of failure to obtain approval. Many of the projects are subject to environmental problems that result in delay and thus a delayed commencement of tolling. When that happens the government compensates the concessionaire for additional design costs, additional consultant costs, and increased costs of environmental compliance, including land cost and cost of improvements. This situation can be extremely expensive.

Right-of-way acquisition cannot be totally delegated to the concessionaire because expropriation (condemnation) rights may be exercised only by the government. In practice, the concessionaires can participate in the acquisition process, doing everything up to the determination of need. The first Portuguese concessions gave the government primary responsibility for acquisitions, with parcels being identified by concessionaires and the government undertaking acquisitions. This method has proved burdensome. The most recent concessions have involved a transfer of significant right-of-way risk to concessionaires, by transferring more and more of the expropriation activities to the concessionaires. Concessionaires handle negotiations, and the government provides the public interest declaration. If contested, the matter goes to court and the government handles the case. The potential for delay in the court proceedings is a government risk. The government also bears the risk associated with any requirements to acquire property outside of the original corridor as a result of environmental approvals. In some cases, the government started acquisition proceedings early and ultimately discovered that the parcels were not needed for the ultimate project configuration.

The aggressive Portuguese concession program involves some adverse impacts. One concern is the loss of owner expertise under this program. In a period of less than 6 years, Portugal has moved from a program with 1 concession to a program with 14 concessions. This shift has enabled the IEP to downsize its engineering and administrative staff, but also has resulted in a loss of valuable expertise. Although the IEP has been relieved of direct responsibility for developing major projects, the IEP must continue to develop design, construction and operation standards, and policies that will be the basis for establishing the scope of the concessionaires' obligations. The loss of expertise will be felt for many years, both in the lack of resources for reviewing future concession proposals and in the administration and oversight of current contracts.

A

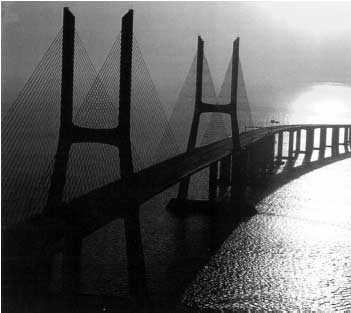

Case Study: The Vasco da Gama Bridge in Lisbon

A

Case Study: The Vasco da Gama Bridge in Lisbon (adapted from Perrot and Chatelus 2000)

The Vasco da Gama Bridge in Lisbon is one of the largest and most interesting concessions in all of Europe. Because of the geographical position amidst the inland sea created by the Tagus River estuary over its course, the length of the bridge was conceived to be approximately 12 km. When including all of the access roads and necessary motorway junctions, the total project comprised a length of over 18 km, with a price tag of some 6 billion francs (approximately US$883 million) including financing costs.

In spite of the subsidies provided by the European Union Solidarity Fund in the amount of about 2 billion francs (approximately US$294 million) (34.5 percent of total needs), the remaining financing required for the project exceeded the capacities of the Portuguese national budget's conventional financing system. For the complementary financing to be borne by the private sector instead of the national budget, the concession formula was chosen. To make this strategy viable, the contribution of subsidies proved essential. Looking at similar projects of the time (doubling the capacity of the Severn River Bridge and of the M25 tunnel under the Thames River in Dartford, England), Portuguese authorities came up with the idea of providing subsidies, of over 600 million francs in all, siphoned from revenues generated by the existing "April 25th Bridge," which had been run as a toll facility ever since its opening. The international tender for the new bridge's financing and construction as well as for the operations of both the new facility and the April 25th Bridge, all lumped into a single concession, was ultimately held in 1993.

In April 1994, the future concessionaire was selected; the contract was awarded to a consortium of construction companies (called "Lusoponte"), composed of:

The definitive concessionary contract was signed on March 24, 1995, with the primary stated objective being the new bridge's service startup prior to March 31, 1998, in time for the World's Fair.

In addition to the contribution of the Solidarity Fund, the plan of finance included an EIB loan for 2 billion francs and approximately 700 million francs in shareholder capital. The remaining amount was financed through a conventional bank loan.

The construction companies participating in this bold project needed strong international credentials in order to cope with the magnitude of the risks involved: financing and building one of the world's premier bridges within a span of 3 years, then assuming the risk of maintaining minimum traffic levels over the concessionary period, set at a maximum of 33 years, with the concession expiring once the number of crossings on both bridges combined has reached the 2.25 billion mark. The concessionaire was even given responsibility for the risk of right-of-way acquisition.

Despite all of the inherent uncertainties in a project of this scope, the Vasco da Gama Bridge was opened for service in accordance with specifications on March 29, 1998. Twenty-one months after its opening, the success of the Vasco da Gama Bridge has surpassed all expectations. Traffic in 1999 soared to 16 million vehicles, for a daily average of more than 43,000 vehicles. Even more extraordinary, however, is the fact that this success has not come at the expense of the older bridge, which reached a record level of crossings in 1999 with more than 53 million (for a daily average of 147,000 vehicles). In two years' time, the total number of river crossings by road has risen by 20 million, for an increase of nearly 40 percent, and this despite the opening of a rail link in 1999 between the two banks built on the April 25th Bridge's foundation. This explosion in the demand for cross-river transportation, subsequent to the significant increase in supply over a two-year span, provides an eloquent illustration of how a program can satisfy the pent-up demand of residents in a rapidly growing region.

The French have a long history of PPPs and concessions. In fact, the nation's first concession was granted to Adam de Craponne in 1554 for the construction of a canal. The Paris Metro is another concession. The City of Paris built the infrastructure, but it is run by a private company, Compagnie du Metropolitain di Paris (Group Empain).

Given this history, it is not surprising that the French utilize concessions for the majority of their motorways. The French use a real toll system with almost 100 percent of the cost for the roads being borne by the user. Tolls account for 65 percent of the capital motorway costs, with 19 percent from the government (3 percent for maintenance and 16 percent for building) and 16 percent from the local authorities (0 percent for maintenance and 16 percent for building). The tolls themselves are spent for financing (63 percent), toll collection costs (26 percent), and taxes (11 percent). The table below provides an estimate of the size and amount of motorways under concession:

| Total Motorways (Jan 1, 1998) | 9,309 km |

|---|---|

| Interurban Highways | 8,319 km |

|

7,048 km |

|

1,271 km |

| Urban Highways | 990 km |

The

French motorways system has steadily grown from 1,125 km in 1970 to more than

11,000 km in 2000. There are nine primary concessionaires, only one of which

(Cofiroute) is fully private. Central and regional government bodies hold the

remaining eight regional concessionaires through limited liability companies

(SEMs). Some of the more profitable SEMs support the other, less profitable

ones. Some public companies have private "firewalls" so they can

compete with the private sector. SEMs are financed by the Caisse Nationale

des Autoroutes (CNA), an autonomous public agency that raises the funds for

highway construction. Private utility companies sometimes operate SEMs under

short-term contracts.

The

French motorways system has steadily grown from 1,125 km in 1970 to more than

11,000 km in 2000. There are nine primary concessionaires, only one of which

(Cofiroute) is fully private. Central and regional government bodies hold the

remaining eight regional concessionaires through limited liability companies

(SEMs). Some of the more profitable SEMs support the other, less profitable

ones. Some public companies have private "firewalls" so they can

compete with the private sector. SEMs are financed by the Caisse Nationale

des Autoroutes (CNA), an autonomous public agency that raises the funds for

highway construction. Private utility companies sometimes operate SEMs under

short-term contracts.

The nine concessionaires are listed in the table on the next page. The adjacent figure graphically depicts the organization of the French government and the concessionaires.

The relationship between the public owner and the concessionaire is very well defined. A 1985 law takes into account the client process, the quality, the cost, and the principles upon which the project is based. It also describes the roles of the engineer and contractor. The public-sector client must state very clearly the needs of the public through a "program," which goes to the designers and contractors or the concessionaires. At the end of the project, the client approves the final product. The mission of the client is to define its needs in the "program" and assess the costs. This law is based on the principle that the client must participate throughout the entire process. When the public owner does not have the necessary expertise, it can employ an owner's representative or it can engage a firm to do the job in the name of the owner (but only in the construction phase). This responsibility cannot be totally transferred to third parties, as the law states that the owner must be present at all

critical points in the process. As a result, these owners' representatives can only be public authorities or quasi-public agencies, and the owner must have a construction manager separate from the construction team. There are two milestones of cost assurance--one at the program level and one at the bidding time. If the bid costs are higher than the target, the engineer has to redesign.

As with the Portuguese concession system, the government has carefully determined the appropriate risk allocation. The figure below describes the risk allocation between the French government and the concessionaire. This table is based on the agreement between Cofiroute and the French government, but it is similar to agreements with the SEMs. The strategy is almost identical to that of the Portuguese government discussed in the previous section; however, the French government is willing to maintain more of the risk from new legislation. Although it is not shown in the table, Cofiroute and the other SEMs can purchase right of way on behalf of the government.

| Revenue and traffic risk | Concession |

| Construction Cost Risk | Concession |

| Financial risk | Concession |

| Operation cost risk | Concession |

| Project risk | French State |

| Force majeure | French State |

| Government action | French State |

A description of Cofiroute's operations provides an excellent example of how the French concession program works. Cofiroute was formed in 1970 and has finished its first concession contract. It has been awarded numerous concessions through 2030 and, in fact, has one concession (the A86 West Loop) with a term ending in 2078 because the project is so large that a notice to proceed with the final segment will not be provided until one-half of the construction is done.

Cofiroute is in charge of designing and constructing the 900-km network. It does this through contracts with its contractor shareholders. It operates, maintains, and collects tolls on its network. Additionally, it is responsible for the safety and service of the customers. Cofiroute is contracted to keep the road available and safe; to restore normal traffic conditions in case of unforeseen events, including providing information to road users and public authorities; to operate traffic flows; to adjust demand to the actual capacity in order to limit or avoid congestion; to assist users; and to provide travel services. To maintain the network, Cofiroute provides emergency assistance through signing and coning, breakdown assistance, coordination with the police, employing emergency response plans, and implementing traffic management methods with other road operators.

It is interesting to note the diversified and central and regional government shareholding of the other eight quasi-public concessionaires. The central funding system is an efficient way of minimizing the cost of finance and of expanding the size of the network. However, both the French and EU authorities are seeking to make the French concession system for roads open to competition, as is already the case in other sectors such as water and wastewater treatment, in which the private companies play a substantial role.

Although not as prevalent as in Europe, concession contracts do exist in the United States. The U.S. Highway 91 express lanes in California provide a case study of how concessions can be successfully implemented. The following case study was written by Jean-François Poupinel, Chairman of Cofiroute, and Carl Williams, Deputy Secretary for Transportation, State of California (Perrot and Chatelus 2000).

On July 29, 1989, as part of a package of bills that among other things would raise the state's gas tax by 9 cents a gallon over 4 years, the California legislature passed AB 680. Its drafters had proposed the legislation to test the efficacy of private involvement in public transportation facilities and to help compensate for the growing disparity between public resources and transportation needs. AB 680 authorized four infrastructure innovative demonstration projects using only private financing. The international competition solicited by Caltrans allowed prequalified private sector consortia to select any project that made both business and transportation sense. Out of thirteen international consortia that expressed interest, ten were prequalified. The "91 Express Lanes" was one of the four projects selected in September 1999. To date it is the only one that has been financed and constructed. [One other (the SR-125 project) is scheduled to close its financing during 2002.]

Located southeast of Los Angeles, California, the SR 91 is a very congested urban freeway linking three of the fastest growing Counties in the US: Riverside, San Bernardino and Orange Counties. Its eight lanes carry more than 230,000 vehicles per day, and is congested more than four hours a day in each direction. As a franchise holder, CPTC (California Private Transportation Company) has built four toll lanes (two in each direction) in the median of the existing non-tolled public highway. This new ten-mile-long facility operates without intermediate access points, and offers a fast, safe and reliable alternative to motorists who wish to save time.

CPTC is a limited partnership. The general partners are subsidiaries of Cofiroute Corporation (the U.S. subsidiary of Cofiroute) and of Peter Kiewit Sons who were in charge of the development and financing. They were joined by an affiliate of Granite Corporation Inc as a limited partner. The development (pre-construction) costs exceeded $ 10 million. The franchise is in force for 35 years. The major project risks were borne entirely by the concessionaire, who could elect to "abandon" the franchise without penalties if the project appeared infeasible. The Franchise Agreement precluded the use of any state or Federal funds, but implemented innovative ideas concerning return on investment, performance incentives and the protection of the concessionaire through a non-competition zone.

This unique and innovative project has accumulated a number of "firsts". It is the first U.S. toll road to be privately financed in over 75 years. SR 91 is the world's first fully automated toll road, and is the first infrastructure project in the world to apply the concept of "value pricing". Since the "competition" offers a non-tolled ride a meter away, it continues to be important to listen at all times to the customers and to give them real "value" for money. To ensure that traffic flow remains fluid on the 91 Express Lanes now used by more than 30,000 vehicles per weekday, tolls were raised four times in the three-year life of the project. A major side benefit of the toll lanes is that traffic conditions have also been dramatically improved on the non-tolled public lanes.

This project, which has set the standard of a partnership between the private and the public sectors including the State of California (Caltrans) as well as local authorities, has received numerous awards including:

- The "Innovative Finance Award" by the Federal Highway Administration in 1992;

- The "Excellence in Transportation Award" by Caltrans in 1994;

- The "Innovative Project Award" by IBTTA in 1996.

The design and construction costs for the SR 91 project were financed through a taxable bank loan. An attempt by the concessionaire to restructure the deal, so as to allow a tax-exempt refinancing, proved controversial politically and was not implemented. The non-compete covenant has also proved to be politically controversial, and recently resulted in an agreement by the Orange County Transportation Authority to pay damages to the concessionaire in connection with construction of improvements to public facilities.

As with selection of design-builders, selection of concessionaires can take many different forms. Add the fact that the government can in part own concessionaires, and the selection process becomes even more complicated. A purely qualifications-based selection had been employed by the French in the past, but they are turning to public competition for the selection of concessionaires today. This change is in part because of the new regulations of the EU, which is attempting to promote competition between EU countries. Refer to Chapter 3 for a summary of the EU policies for award of public works contracts, including concessions.

Two of the host countries, Portugal and the Netherlands, formally outlined their concessionaire process for the scan team. These processes are presented as two individual cases. However, as in the United States, selection systems vary on a project-by-project basis depending upon the characteristics of the projects and needs of the owner.

Because Portugal is operating under the new EU rules and is involved in a significant number of concession agreements, the Portuguese have created a rigorous and repeatable selection procedure. The legal framework for the selection was established and published for open procurement on the EU market. The procurement involves an international public tender in two stages, with no prequalification in the first phase.

The procurement process gives the concessionaires 5 months to prepare their proposals following receipt of the request for tenders. The proposals are then presented to the IEP. Since the proposals involve design, construction, operation, maintenance, and other services, the evaluation is quite complex and takes up to 6 months to complete. The proposals are evaluated on the following criteria:

| Publicity (J OCE) | 0 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bids preparation | 5 months | |

| Bids Presentation | 5 | |

| Evaluation | 6 months | |

| 2 bids shortlisted | 11 | |

| Negotiation | 4 months | |

| Contract Award | 15 | |

| Finalising legal requirements and contract terms | 3 months | |

| Financial Closing | 18 | |

Two proposers are shortlisted after evaluation, and the IEP enters into competitive negotiations with the proposers. The final completion of the contract terms and contract award is accomplished in 3 months. The entire selection process takes an average of 18 months to complete.

The British and the Dutch also are giving careful consideration to the selection of concessionaires and public-private ventures. These countries have developed a tool for the evaluation of both the concession project and the concessionaire selection. The Public-Private Comparator (PPC) is employed to make a financial comparison of the viability of using a concession versus keeping a project in the private sector. The PPC compares the NPV of the concessionaire's proposal with the traditional cost of design, construction, maintenance, and operation in the traditional method. In this manner, the agencies can compare not only alternative concessionaires' proposals, but also the traditional procurement method.

The Dutch have incorporated the PPC into their selection procedure. The DBFM N31 road project provides an example of a selection process utilizing the PPC. The project involves improvements required for traffic safety/traffic flow reasons--the current road is one lane in each direction, and the new road will be two lanes in each direction. The road is approximately 25 km in length, and includes one bridge and an aqueduct. The estimated construction cost is US$125 million. RWS determined the advantages and disadvantages of concession in a systematic and transparent way, using the PPC and based on an estimate of the NPV, cost, and benefits associated with the project. The study concluded that DBFM would be an efficient means of proceeding with the project, and also that there was no significant difference between DB and DBFM. Based on the PPC, RWS decided to proceed with the project as a DBFM pilot project. The proposed contract includes 15 years of maintenance. RWS also is asking for an alternative bid for 30 years of maintenance. The tender process is a combination of requirements of Dutch law and the EU Directive, and includes the following steps:

The contract will include incentive/disincentives based on road availability to encourage safety and minimize congestion. The contractor will be subject to penalty points for not following standard procedures to ensure safety. If too many penalty points are received, payment will be reduced. If the contractor's performance still fails to improve, at some point RWS will issue a warning followed by termination of the contract for cause. Please refer to Chapter 5: Performance Contracting for more information on the Dutch incentive/disincentive system.

Traditional U.S. contracts do not directly tie construction requirements to long-term performance. Once construction is complete, the contractor or design-builder typically provides a 1-year warranty. Concession agreements go far beyond simply warranting a project. By tying long-term operation and maintenance into the contract, the concept of warranty becomes irrelevant. Concessionaires are responsible for designing and constructing facilities that meet performance criteria over a long duration. This process creates a lifecycle mentality for the concessionaire from initial planning through contract closeout.

Durations of concessions were found to range from less than 5 years to more than 75 years, but the majority of concessions were contracted for 15 to 30 years. Maintenance contracts in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom tend to have a term in the range of 5 years. The majority of design-construction concessions of major motorways were in the range of 25 to 30 years. Many of the contracts also contained windows of profitability for determining the end of the contract because traffic forecasts for 30 years in the future are questionable. If traffic forecasts are wrong, there are only two options for equitable compensation for the project: change the rate of tolls (or payments) or change the duration of the contract. Political and financial viability typically limit changes in the rates charged. Possible solutions to problems caused by inaccurate traffic forecasts are to provide some mechanism for changing toll rates and, if necessary, changing the total duration of a concession to provide an equitable compensation to the concessionaire.

Another issue that must be addressed in concession agreements is the condition of the project upon delivery to the government at the end of the concession period. The Dutch are promoting concession periods with a duration equal to 75 percent of the design life of the product. This rule applies only when the concessionaire designs and builds the project. For maintenance and operation contracts on existing roads, the concessionaires in essence bid on the rights to operate and maintain the road in return for the toll collection or shadow toll payments from the government. The appropriate standard to be met at the end of contract life is not clear-cut in these situations. Concessions on existing facilities must be assessed on a project-by-project basis.

As described in the previous section, the role of a concessionaire goes far beyond simply warranting a project. Not only do the concessionaires have to maintain prescribed quality for the government, but they also must prove to their financial lenders and shareholders that they are delivering and maintaining a quality product. From what the host concessionaires described on the scan tour, these lenders and shareholders are sometimes more demanding than the States have ever been.

The question for the government is then how best to specify and measure the performance of the concessionaire. This question might best be answered through a discussion of the frameworks for the two concessionaires visited on the scan: the French concessionaire Cofiroute and the Portuguese concessionaire Autoestradas do Atlantico (AEA). Additionally, Chapter 5: Performance Contracting provides specific contract clauses for maintenance and operation contracts.

Given the nature of long-term contracts and high levels of competition for concessions globally, the concessionaires must maintain a high level of performance in order to remain competitive. It is well known that Cofiroute has one of the best asset-management systems in the world. In addition to its concessions in France, Cofiroute has concessions in the United Kingdom, South Africa, Los Angeles, Portugal, Argentina, Byelorussia, and others. It is the private ownership of the company that drives it to continuously measure the condition of and improve its assets--namely, its global highway network. The adjacent picture shows Cofiroute's pavement assessment vehicle, which is used to continuously monitor the condition of its roadways. Cofiroute boasts one of the most sophisticated and technically advanced asset-management systems of any private company or public agency.

AEA has a shorter history than Cofiroute, but its function is essentially the same.

AEA is located north of Lisbon in a rural but growing area. AEA runs a concession

on a highway that is about 8 to 10 years old. It believes that the traffic

will increase substantially as Lisbon grows. The performance terms of AEA's

contract includes:

AEA has a shorter history than Cofiroute, but its function is essentially the same.

AEA is located north of Lisbon in a rural but growing area. AEA runs a concession

on a highway that is about 8 to 10 years old. It believes that the traffic

will increase substantially as Lisbon grows. The performance terms of AEA's

contract includes:

Regardless of whether the agencies are responsible for measuring concession performance or the concessions measure their own performance, with performance audits undertaken by the agencies, performance measurement and benchmarking are the cornerstones for the success of any concession contract. More specific information concerning the measurement and assessment of long-term contracts is provided in Chapter 5: Performance Contracting.

Motorways in Europe utilize concessions for both construction and maintenance. The long-term nature and best-value selection of a concessionaire provides the opportunity to benchmark and achieve exceptional performance. All of the host countries visited on this contract administration scan are incorporating concessions into their strategic networks plans--some at a smaller maintenance and operation level and some for the majority of their networks. Appropriate selection of concession projects and concessionaires will be one of the keys to successful incorporation of this contracting strategy into the United States. Agencies must consider the specifications and measurement of performance criteria carefully because typical concessions last for 25 to 30 years. Used in appropriate circumstances, concession contracts may prove to be very beneficial to the U.S. highway sector. The scan team recommends that the following issues be explored in the United States as a means to speed the delivery of our infrastructure and increase the quality of construction and maintenance:

| << Previous | Contents | Next >> |